Commercial and recreational fishers have contributed hundreds of fish samples to help develop new ways to detect ciguatera toxins, as part of FRDC funded food safety research.

Marine toxin specialist Professor Shauna Murray is leading the ciguatera toxin (CTX) detection project at the University of Technology Sydney, working closely with commercial and recreational fishing sectors, Sydney Fish Market, University of Tasmania and New Zealand’s Cawthron Institute.

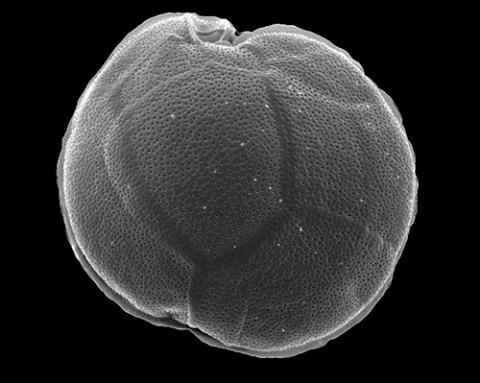

Ciguatera toxins are produced by single-celled Gambierdiscus micro-algae, a warm water-loving genus, which work their way up the food chain to accumulate in predatory, apex tropical reef fish species.

Gambierdiscus micro-algae produce toxins that can accumulate in higher apex tropical reef predator species. Photo: UTS

When people eat fish that has accumulated these toxins, it leads to ciguatera fish poisoning (CFP), the leading cause of seafood-related food safety incidents in Australia. This results in a combination of gastrointestinal and neurological symptoms, typically a reversal of hot and cold sensation, which can last from days to several months.

CFP is still relatively rare in Australia, but occurrences have been moving southwards from Queensland to northern NSW over the past decade. In Australia, it is most commonly found in tropical fish species.

Detecting the toxins

The toxins themselves are difficult to detect in fish; they are colourless, odourless and don’t break down when the fish is cooked. The Sydney Fish Market limits the size of certain species prone to CFP as a risk management strategy.

Part of Shauna’s current research is trying to confirm a link between the size of fish and the presence of toxins.

To help do this, Dr Arjun Verma from the UTS team has coordinated the sampling contributions from the Sydney Fish Market, commercial fishing cooperatives as well as recreational fishing clubs in northern NSW and Queensland. They have collectively contributed more than 250 fish samples to the study from the 2020–22 fishing seasons.

“Over the past two years, they have helped us to gather samples of fish across all size and age ranges, from five kilograms to more than 20 kilograms,” says Shauna. “We really needed the whole range to understand the relationship between toxins and size.”

Flesh and liver samples from each fish were processed at the Sydney Institute of Marine Sciences and submitted for testing to the Cawthron Institute, which uses a process called liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LCMS) to detect the presence of ciguatera toxins.

Chowdhury Sarowar at the Sydney Institute of Marine Science biotoxin facility prepares Spanish Mackerel samples supplied by recreational and commercial fishers to test for ciguatera toxins. Photo: SIMS

These have been combined with samples from previous research dating back to 2016, collected largely from the Sydney Fish Market, with results now being analysed.

Rapid testing

The LCMS results provide a basis for comparing the effectiveness of simpler cell-based tests, which could provide a faster and cheaper way of testing. Shauna says these cell-based tests will measure the impact of the toxins on cells, rather than look for the toxins themselves. “Based on that impact, we can work out how much toxin is present in each cell,” she explains.

Dr Andreas Seger at the University of Tasmania has led the test-kit analysis, with 2 different kits; one is a commercially available test, whilst the other is a cell-based test commonly used in laboratories to test marine toxins.

“We’ve had some success detecting toxins with these kits, so now we’re trying to assess whether they will be practical and economically feasible to use at the Sydney Fish Market, for instance.”

In conjunction with this work, Professor Bill Gladstone at UTS has gathered data on migratory patterns to help assess how environmental conditions might be contributing to the presence of toxins in prone fish species. “We found there was a lot of information out there, but pieces of it were held in many different places. We’ve basically pulled it all together,” says Shauna.

FRDC Research Program Manager Adrianne Laird says popular coastal commercial and recreational species in Queensland and northern NSW are most at risk to CFP.

“FRDC’s NSW Research Advisory Committee identified the need for this research as a priority to help these sectors and enable the sale and consumption of safe seafood. So, it will really benefit those who love to catch the fish, and those who just love to eat it too,” Adrianne says.

In the final six months of the project the research team will combine the results of its three elements to identify any potential new management strategies. The end goal is to reduce the risk of ciguatera fish poisoning, protect public health, and protect the overall reputation of seafood as a safe and healthy food. The final report is expected to be complete by the end of the year.

More information

- FRDC Project: 2019-060: The Detection of Ciguatera Toxins in NSW Spanish Mackerel

- Ciguatera Fish Poisoning

https://www.foodauthority.nsw.gov.au/consumer/food-poisoning/fish-ciguatera-poisoning

- SafeFish is primarily funded by the Fisheries Research & Development Corporation (FRDC) and is the leading platform in their program for dealing with food safety and trade and market access issues affecting Australian seafood. https://www.safefish.com.au/reports/food-safety-fact-sheets/ciguatera-fact-sheet

This reflects R&D Plan Outcomes 1, 2 and 5