The rise in whale numbers along Western Australia’s coast has prompted new research to reduce the risk of entanglements in fishing gear

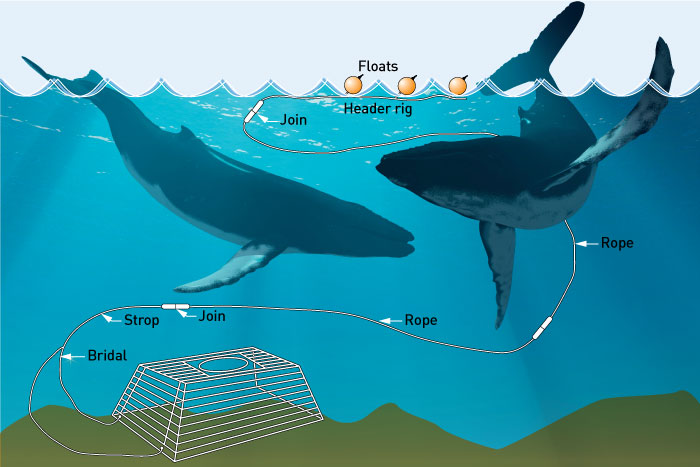

A typical Western Rocklobster fishing set up.

A typical Western Rocklobster fishing set up.By Sarah Clarry

The West Coast Rock Lobster Managed Fishery in Western Australia has been a spectacular success story since moving from an input control management system to an output (or quota) control management system in 2010-11.

The quota system with a year-round fishing season has allowed fishers to spread the catch throughout the year. In doing so, higher beach prices have been maintained. Fishers now fish to demand and catch the amount and sizes that will deliver the best profit. It has also contributed to a healthier rocklobster population.

But the year-round fishing has also coincided with an increase in the number of whales getting caught in rocklobster fishing gear.

Since 1990, there have been 130 entanglements recorded in WA; of these, 128 involved commercial fishing gear. Since 2010, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of whale entanglements in commercial gear (with most of them being in rocklobster fishing gear).

In 2013, there were 18 reported entanglements in lobster gear, well above the long-term average of whale entanglements for this fishery, which until then was between zero and four (average 1.72) per year.

Entanglements can lead to injury or death of the animal (although no deaths have been recorded as being caused by rocklobster gear), sometimes many hundreds of kilometres from the initial site of the entanglement.

Whales are a protected species under Australian legislation and the West Coast Rock Lobster Managed Fishery is acutely aware of the need to reduce the number of entanglements.

The industry is working collaboratively with researchers, as part of an FRDC-funded project, to trial measures including modifications to fishing gear, technologies such as audio pingers and

acoustic or anode remote release systems.

Project leader Jason How explains: “Whales move through our coast from May to November. The old rocklobster season ended in June, by which point there was not a lot of fishing occurring, with low catch rates and poor weather conditions. So the bulk of [whale] migration occurred when no one was out fishing.”

However, he says the change to the season length cannot be the only reason for the increase in entanglements.

“We are also seeing more entanglements in the ‘old’ part of the season, that is, earlier than expected. The season change may have meant subtle changes to fishers’ behaviour and we are trying to pinpoint what these are,” he says.

“There are also a lot more whales. The Humpback Whale population that uses the WA coast is one of the fastest recovering whale populations in the world.” Humpback Whales account for more than 90 per cent of entanglements with rocklobster gear.

Jason How suspects that differences in the timing of entanglements between years may be the result of changes in timing of whale migrations, which have seen whales arriving on the west coast later than in other years, or weather conditions that may exacerbate entanglements. He says the FRDC is funding further research to evaluate the impact of these issues.

“We want to make contact with other scientists undertaking work on the modification of fishing practices to reduce whale entanglements,” he says.

“We have been encouraged by the assistance from industry. While it would be good to have more feedback from fishers, several have taken time and considerable effort to test the new gear and undertake a number of surveys. Industry is working strongly with government to find a solution to whale entanglements for the good of both the industry and the whales.”

With increased awareness of the issue there has already been a decline in whale entanglements in commercial rocklobster gear this year; seven incidents were recorded between January and

October 2014.

Whale watch records

To examine the dynamics of Humpback Whale migration along the Western Australian coast, researchers use information from two sources: the cetacean stranding database (which monitors dolphins and porpoises as well as whales), and the commercial whale-watching database. Both are managed by the WA Department of Parks and Wildlife, the state’s lead agency for whales.

A new whale-watching app, Whale Sightings WA, is expected to help researchers gather more information, providing a way to tap into the state’s extensive network of water users and whale watchers.

This includes commercial operators and members of the public, who will be able to report sighting of various whale species via the app.

More accurate, up-to-date information about when and where whales are travelling may allow fishers to choose alternative locations to set their pots.

FRDC Research Code: 2013-037, 2014-004

More information

Jason How, 08 9203 0247

jason.how@fish.wa.gov.au