As host of the World Aquaculture Society’s 2015 annual conference, South Korea profiled the successes and challenges of its industry

Often served raw, Olive Flounder is the iconic species of the South Korean aquaculture industry, and was a feature of the menus during the international aquaculture conference.

Often served raw, Olive Flounder is the iconic species of the South Korean aquaculture industry, and was a feature of the menus during the international aquaculture conference. Photo: 123RF.com

By Catherine Norwood

With a firm, white flesh and a delicate flavour Olive Flounder (Paralichthys olivaceus) is commonly eaten raw and features on many Korean and Japanese menus. Marketing focuses on its nutritional analysis, highlighting the “collagen rich” texture of the flesh, which is “high-protein, high-lysine and low in fat”.

Olive Flounder is the flagship species of South Korea’s aquaculture industry. It is the world’s largest producer and exporter of the species, with production in 2013 of 37,000 tonnes, worth about US$430 million – or 58 per cent of the South Korea’s total aquaculture value.

About 10 per cent of South Korea’s production is exported, most of which goes to Japan, with buyers in several other Asian countries as well as in the US, Canada and Russia.

The species also exemplifies many of the challenges facing the industry in South Korea as it moves to modernise and expand production of this and other fish including several gropers and bream.

Olive Flounder production in South Korea dates back to the 1980s when the native species was first identified for culture. Industrial-scale production began in 1989.

Flatfish such as flounder are popular around the world and this has placed pressure on many wild fisheries. The strong demand makes these and similar species strong candidates for culturing.

Jeju production

A national Olive Flounder breeding program is underway and is now in its fourth generation, with an increased focus on disease resistance and preserving genetic diversity while still improving growth rates by 30 per cent. Olive Flounder are grown in land-based systems, developed after ocean-cage production proved inefficient.

More than half of the national production comes from Jeju Island, where the industry has a natural geographic advantage that allows year-round production. Fish grown here reach market size – 0.9 to 1.1 kilograms – 1.7 times faster than in other production centres.

Most aquaculture farms in Jeju are able to use high-quality underground seawater as either their sole water source or in combination with the island’s unpolluted seawater. The underground water remains at a steady 16°C to 18°C year round, reducing energy costs involved in heating the water to achieve optimal fish growth, which occurs at 21°C to 24°C.

While disease outbreaks, exacerbated by high stocking densities, reduced national production from a peak of 54,574 tonnes in 2009 to 36,921 tonnes in 2014, production from Jeju Island was less affected, declining from 26,047 tonnes in 2009 to 23,000 tonnes in 2013.

Feed challenge

Photo: www.jejuflounder.com

Photo: www.jejuflounder.comIn providing a general overview of South Korean industry at the World Aquaculture Society conference the head of the Fisheries Policy Department Ministry of Oceans and Fisheries, Yeong-Hoon Jeong, said food safety for consumers was the first priority.

The widespread use of moist pellets made of fresh and frozen fish bycatch and byproducts presented a significant challenge for both the Olive Flounder industry and aquaculture in general in South Korea. He said it was difficult to manage food safety when farmed fish were fed on raw fish.

Promoting the use of high-efficiency, extruded pellet technology for industry is a priority for the South Korean Government, with a ban on moist pellets expected to come into force in 2016. The aim is to promote fish health, increase production, traceability and food safety, and to improve the fish-in fish-out feed ratio.

The 3:1 ratio using moist pellets has improved to a reduced rate of 1.2:1 through a combination of improved extruded pellet feeds and fish genetics.

Consumers were also increasingly demanding that producers should properly manage the health of their fish. He said this would require supporting improved production practices to prevent and reduce disease, including better feeds, as well as the development of improved vaccines and medicines.

Yeong-Hoon Jeong said other challenges for aquaculture overall included developing a more environmentally sensitive industry. Highly concentrated, high-intensity farming in some coastal areas had resulted in environmental degradation.

He said high-intensity farming and a focus on selection of stock for growth had also led to a loss of genetic diversity, more widespread occurrence of deformities, and more frequent and severe disease outbreaks.

The adoption of multi-trophic farming and greater use of biofloc and recirculation systems were expected to help address this but he acknowledged that a shift in perspective towards a greater ecological awareness across the industry was needed.

New species

Initiatives to address this include breeding programs at the Future Aquaculture Research Center in Jeju. The centre has a mandate for the preservation of indigenous species and the development of culturing techniques and genetic improvement for aquaculture.

At the centre, the Olive Flounder improvement program is now in its fourth generation of genetically improved broodstock. However, the other 31 species raised at the centre – some still being evaluated for commerical potential, or species preservation – continue to be bred from wild-harvested broodstock. This includes turbot, which is often produced commercially in conjunction with Olive Flounder.

The South Korean Government has selected flatfish (flounder, turbot and halibut), serranidae (groupers and bream) and abalone among its national export-focused agricultural investment priorities.

While South Korea already commercially cultivates 29 species on an industrial scale, it will continue to “put energy into value-added and high-value species in global markets, such as bluefin tuna and groupers”, Yeong-Hoon Jeong said. And, of course, Olive Flounder.

Breeding for new Markets

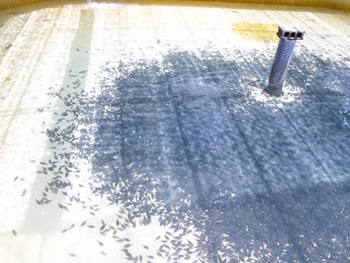

Olive Flounder production systems typically involve shallow pools, which are also used for turbot production. Delegates to the World Aquaculture Society conference toured several fish farms, including the Beebong Aquaculture Farm on Jeju Island, which produces 300 tonnes of flatfish a year, using a combination of seawater and marine groundwater.

Olive Flounder production systems typically involve shallow pools, which are also used for turbot production. Delegates to the World Aquaculture Society conference toured several fish farms, including the Beebong Aquaculture Farm on Jeju Island, which produces 300 tonnes of flatfish a year, using a combination of seawater and marine groundwater. Photo: Catherine Norwood

Efforts to add value to the product include initiatives such as Jeju Garlic Flounder – a marketing initiative of the Jeju Flounder Co. to promote the local provenance from Jeju Island in the country’s south as a global brand. Value-adding for this brand includes the addition of lactobacillus from fermented garlic into the feed, to enhance the nutritional benefits of the raw fish flesh.

A genetically focused initiative, Golden Olive Flounder, is also underway. In the wild a rare mutation results in flounder of a vivid golden colour.

Researchers working with the Korean Fish Breeding Research Institute have a program to stabilise the colour genetics; the product is already attracting strong interest from Asian markets.

Chinese view on fish farming

Also providing a keynote address at the World Aquaculture Society 2015 conference was Kangsen Mai, a professor at the Ocean University of China specialising in fish nutrition. He took the opportunity to defend China’s reputation as the world’s largest producer of farmed fish.

He responded to the “anti-aquaculture noise” that had accompanied the publication of an article in Science magazine (January 2015) raising concerns about the potential of China to deplete wild fish stocks to feed its expanding aquaculture industry.

Kangsen Mai said China farms more than 160 different species of fish and seafood, and more than half were not dependent on fish-based aquafeeds. About 50 per cent of Chinese production comprised filter feeding or herbivorous species. Omnivorous species account for 42 per cent of production and carnivorous species account for eight per cent of production.

He said while aquaculture production in China has continued to increase steadily, consumption of wild fishmeal has remained relatively steady at about 1.6 million tonnes since 2000. Only 55 per cent of this is used in aquaculture.

Total fish and fishmeal used in aquaculture totals seven million tonnes to produce 28 million tonnes of seafood for human consumption (excluding mollusc production), with an overall fish-in fish-out ratio of 1:4. Removing filter feeders from the production total still results in a ratio of 1:3.2 – and a feed-conversion ratio that is two to seven times more efficient than that of land-based animal farming, he said.

In terms of improving human health and nutrition, aquaculture has allowed China to lift its per capita consumption of fish protein from 9.5 kilograms per person in the 1960s to 36.6 kilograms in 2013. China’s seafood exports also add about four million tonnes to the seafood available in other countries.

Aquaculture accounts for 70 per cent of national fisheries production in China, which is responsible for two-thirds of the world’s total aquaculture production.

While fish remain as the last wild food on the dinner table, Kangsen Mai said he believed the domestication of fish was inevitable: “Fish will follow the same fate as sheep, goats, cattle, pigs and poultry.”

And while farming of land animals had not been successful in preserving related wild species, he said that given the vastness of the oceans, maybe this could be achieved for fish species, by gradually replacing wild stock with farmed fish.