A diverse range of stakeholders keen to improve marine productivity are coming together to investigate the potential benefits of shellfish reef restoration

By Catherine Norwood

The re-establishment of shellfish reefs around the country is the focus of a growing number of habitat restoration research projects, which aim to improve biodiversity, water quality and the productivity of estuarine fisheries.

Projects are already underway in most Australian states, and the Australian Shellfish Reef Restoration Network was formed last year to help researchers and other stakeholders share information and inspiration.

The 2014 FRDC-funded report Revitalising Australia’s Estuaries identified shellfish reefs as a priority for habitat restoration. The report’s principal investigator, Colin Creighton, says shellfish reefs are a comparatively easy and logical place to start to improve the health of estuaries and nearshore fisheries.

“Shellfish reefs have an important role in providing habitat, maintaining water quality and protecting the shoreline from wind and wave erosion,” he says.

Reefs are formed by high densities of oysters or mussels that build up over time, and can grow to several metres high, stretching along kilometres of coastline.

In Australia these reefs were once common in subtidal or intertidal areas, some based on a single species, and others a combination of different oysters and mussels.

New shellfish attach themselves to the layers of dead shell material below, which allows the reef to grow in size and mass, creating a complex, three-dimensional structure that offers food and shelter to other marine life.

Work in Chesapeake Bay, in the US, has demonstrated massive increases in fish and crustaceans with the re-establishment of shellfish reefs. An early trial at Pumicestone Passage in south-east Queensland has also found that reefs provide habitat for fish spawning.

Shellfish are filter feeders and strip nutrients out of the water column, which helps to improve water quality for other marine life. They also re-process fine clay in sediment into larger, heavier aggregations, which are less likely to be re-suspended through wind-wave action.Following the FRDC report, Creighton and a team of researchers led by Ian McLeod from James Cook University and Chris Gillies from The Nature Conservancy have been working with the National Environmental Science Program (NESP) Marine Biodiversity Hub to identify the total value of shellfish reefs to the marine food chain.

Their first report, Shellfish reef habitats: a synopsis to underpin the repair and conservation of Australia’s environmentally, socially and economically important bays and estuaries, was released last year through James Cook University.

As an international environmental agency, The Nature Conservancy has been driving several restoration initiatives already underway in Australia, building on its experiences with shellfish projects in the US.

Chris Gillies, The Nature Conservancy Australia’s marine manager, says that globally, 85 per cent of shellfish reefs have been destroyed, making them the most threatened marine ecosystem in the world. According to the NESP report, Australia has lost 99 per cent of native shellfish reefs, and they are “functionally extinct” ecosystems in this country.

Surviving reefs have been found in Hinchinbrook Channel (Queensland), Sandon River (NSW) and Georges Bay (Tasmania). Only the Tasmanian reef remains actively commercially productive, with two licences for the harvest of wild Native Oysters (Ostrea angasi). (Most Native Oysters commercially available are the product of aquaculture).

Leaf Oyster reef in northern Queensland, with Hinchinbrook Island in the background.

Leaf Oyster reef in northern Queensland, with Hinchinbrook Island in the background.Photo: Ian McLeod

Project leaders for the OceanWatch initiative Sydney’s Living Shorelines, Andy Myers and Simon Rowe, trial different bagging techniques for oyster shells, to create a foundation on which new reefs can form.

Project leaders for the OceanWatch initiative Sydney’s Living Shorelines, Andy Myers and Simon Rowe, trial different bagging techniques for oyster shells, to create a foundation on which new reefs can form. Photo: OceanWatch Australia

Fading memory

At Primary Industries and Regions South Australia, and through research at the University of Adelaide, manager Heidi Alleway has been trying to understand the extent of lost habitat. A search through the SA archives has found fisheries records dating back to the early 1800s that reveal Native Oysters provided the state’s first significant commercial fishery.

“The records indicate that commercial harvesting from natural oyster reefs occurred along 1500 kilometres of the South Australian coastline,” she says. But by 1910 the reefs had been overexploited, and suffered such a significant decline, as a result of harvesting and poor water quality, that they have never recovered.

There is mounting evidence that similar highly productive shellfish reefs also existed along other parts of the Australian coastline. Collectively, the fact that the reefs and related commercial fisheries ever existed has been largely forgotten.It is the recreational fishing community that is emerging as the champion for reef restoration projects, with Victoria and Queensland leading the way.

State by state

Victoria

In Victoria, Albert Park Yachting and Angling Club member Bob Pearce has fished in Port Phillip Bay for close to half a century. He says while club members have been concerned about declining catches of their favourite recreational species, such as snapper, they also wanted to do something about the major decline in the health of shellfish reefs in the area as a basis for rebuilding biodiversity and fish stocks.

Bob Pearce says the reefs used to be “lush”, with large numbers of shellfish often washing up on beaches after storms. But in the early 1980s they suffered a major decline, attributed to the impact of dredging and water quality in the bay. Pollution and disease are other likely contributing factors.

“Local knowledge tells us what used to be there, and what could be there again,” he says. The three-year Victorian trial has received $300,000. The angling club has contributed $50,000, with the bulk of funding from Fisheries Victoria and The Nature Conservancy. University of Melbourne researchers are also providing assistance with the trial design and monitoring.

The Victorian project is the first in The Nature Conservancy’s Great Southern Seascapes initiative, which has expanded to include shellfish reef projects in South Australia, Western Australia and Queensland.

The Nature Conservancy’s Victorian project manager Simon Branigan says there is natural recruitment of both Native Oysters and Blue Mussels (Mytilus edulis) in Victorian waters. However, they are “substrate limited” – there are few hard surfaces shellfish can attach themselves to as foundations for new reefs.

There are two trial sites, one at Hobsons Bay, off the Melbourne suburb of St Kilda, and another in Corio Bay, south of Geelong. Trials began in 2014, with limestone rubble used to create a foundation to lift shellfish off the bottom, and prevent them being smothered by mud and sedimentation. Future trials will incorporate recycled shells collected from restaurants and seafood wholesalers in Geelong.

The limestone substrate was seeded with Native Oysters, produced at the Victorian Shellfish Hatchery, and Blue Mussels, from Advance Mussel Supply, with some natural spat settlement.

Simon Branigan says phase one results surpassed expectations, with more than half of shellfish seeded onto the substrates surviving six months after deployment. Elevation proved critical to survival and it appeared that the larger the oysters when seeded, the more likely they were to survive. “We’re getting closer to proof of concept,” he says.

Planning for phase two of the trial is underway, and will involve expanding the foundations from several independent one-metre-square blocks to four 20-metre-square plots at each trial site.

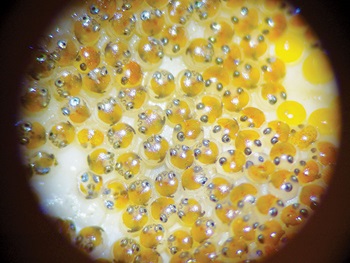

Fish eggs deposited on a trial reef site at Pumicestone Passage, Queensland.

Fish eggs deposited on a trial reef site at Pumicestone Passage, Queensland.Photo: Ben Diggles

Extensive intertidal oyster reefs existed along many parts of the NSW coastline, including the Hunter River region where shell materials in Aboriginal middens date back more than 6000 years.

Extensive intertidal oyster reefs existed along many parts of the NSW coastline, including the Hunter River region where shell materials in Aboriginal middens date back more than 6000 years.Queensland

In Queensland, local community groups including recreational fishing clubs, oyster farmers, traditional owners and community conservation groups have all shown strong interest in shellfish reef restoration in Pumicestone Passage, between Bribie Island and the mainland. Together they have established the organisation ‘restorepumicestonepassage.org’ to support related initiatives.

Marine biologist Ben Diggles, from fish health consultancy DigsFish Services, says subtidal Sydney Rock Oyster (Saccostrea glomerata) reefs occurred naturally throughout Pumicestone Passage prior to European settlement in 1824. By the 1860s, oyster harvesting was one of Queensland’s largest industries.

The industry peaked in the early 1890s but declined as south-east Queensland became more intensively developed. Today the region’s subtidal shellfish reefs are functionally extinct in the area and a continuing decline in water quality has become a major community concern.

Ben Diggles had been working with local oyster farmers and recreational fishing clubs on a range of issues and recognised that both groups shared common concerns about the health of local fisheries and the estuary. He says the potential of shellfish reef restoration to address these issues has brought these groups together. One of the fishing clubs, the Pumicestone Passage Restocking Fish Association, has already re-allocated $50,000 originally raised for restocking finfish into the estuary to shellfish restoration instead. Its members now consider that shellfish restoration will provide much better “bang for their buck”.

Ben Diggles’ preliminary research suggests that restoring reefs is likely to pay off in terms of marine biodiversity.

Small-scale trials have measured substantial increases in recruitment of oysters, fish and invertebrates at the trial sites. The preliminary data suggest improvements in fish and invertebrate biomass of up to 1000 per cent if subtidal shellfish reefs were restored in Pumicestone Passage on a large scale.

The potential of shellfish to improve water quality has also attracted the interest of local councils, and water and catchment management authorities who have contributed funding to research. In the US, a single Eastern Oyster (Crassotrea virginica) has the capacity to ‘filter’ 200 litres of water a day, although it is not yet known whether Australian species match this capacity.

Ben Diggles says the ultimate aim of the restorepumicestonepassage. org group is to scientifically quantify the ecological benefits of shellfish reefs.

This will underpin the business case for investment in environmental offsets, which will help fund larger-scale projects to re-establish self-sustaining shellfish in Pumicestone Passage and throughout south-east Queensland.

South Australia

In South Australia, RecFish SA has been lobbying to increase recreational fishing opportunities, and has supported the use of South Australian government funding for a new artificial reef project to incorporate the re-establishment of a Native Oyster reef. The $600,000 project, which is in its design phase, will create a new recreational fishing hotspot across a four-hectare site near Ardrossan, in the Gulf St Vincent.

RecFish SA executive director David Ciaravolo says he hopes the oyster reef element of the project proves successful and can kickstart the self-sustaining formation of what once existed naturally.

“As we get a greater understanding of the habitat we have lost, through Heidi Alleway’s work for instance, it does paint a picture of the potential greater productivity of our fisheries, if they had the right habitat,” he says. “We have the opportunity to make an enormous long-term improvement to recreational fishing and potentially commercial fishing.”

Other project partners include The Nature Conservancy, South Australian Research and Development Institute, South Australian Tourism Commission, Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources and the University of Adelaide.

New South Wales

A project in Sydney Harbour is an initiative of OceanWatch Australia in partnership with a wide range of organisations, from local councils, oyster farmers and seafood processors to universities. The project focuses on Sydney Rock Oysters and has two overarching objectives: shoreline protection and oyster reef restoration.

Program managers Simon Rowe and Andy Myers are leading the OceanWatch project, called Sydney’s Living Shorelines. The first pilot in Sydney Harbour has five sites marked in inter-tidal areas, with trials to begin this year.

Nine tonnes of waste oyster shells are being collected from commercial oyster farms in NSW and from Sydney restaurants including the Star Casino. These shells are then packed in biodegradable, custom-designed coir (coconut fibre) mesh sacks to form pillows to provide the foundation for new reefs.

Over time oyster spat in the water column will settle on the old shells and as they grow this will bind the structure together.

The University of NSW’s Water Research Laboratory has provided engineering support to optimise the design of the mesh sacks to disperse wave energy, which contributes to erosion.

Local volunteers, including schools and landcare groups, are helping with the project, packing the shell sacks and helping to install them at the trial sites.

Simon Rowe says the project can help inform the community about the value of shellfish reefs and other marine habitats and provides the opportunity to get involved in their rehabilitation.

“The project is attracting a lot of attention from councils as the technique provides a natural, low-cost alternative to erosion control in some situations. It also diverts shells from landfill into natural resource management projects that can deliver long-term ecosystem benefits,” he says.

The project is supported by the Coastal Councils Group, the Greater Sydney Local Land Services and the Australian government, with the University of Sydney and Macquarie University also undertaking related research projects.

Close-up of Native Oysters, South Australia.

Close-up of Native Oysters, South Australia. Photo: Heidi Alleway

Native Oyster bed, Tasmania.

Native Oyster bed, Tasmania.Photo: Chris Gillies

Western Australia

On the other side of the continent, The Nature Conservancy is leading a Western Australian feasibility trial to re-establish Native Oyster reefs at Oyster Harbour, Albany. The WA Recreational Fishing Initiatives Fund is contributing funds, with support from Recfishwest, the WA Department of Fisheries, Western Australian Museum, University of Western Australia and South Coast Natural Resource Management Authority.

Laterite, a type of rock found naturally in Oyster Harbour, has been used to create a substrate for oysters, which have been reared at the Frenchman’s Bay hatchery at Albany and were seeded onto the prepared substrate earlier this year.

Recfishwest’s CEO Andrew Rowland says there has been strong recreational fishing support for the project. “Recreational fishers understand that healthy waterways underpin healthy fish stocks, and we strongly support protecting and restoring fish habitat which will then ensure enjoyable experiences for an estimated one-third of the population who like to wet a line.”

Working with the community, the project will develop a baseline understanding of historical and current oyster populations in order to guide future restoration efforts. If this year’s trial is successful, the aim is to begin large-scale restoration activities from 2017.

Tasmania

Based at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, marine biologist Christine Crawford says interest in shellfish reef restoration has been gaining momentum in Tasmania, although no specific projects are underway.

The Nature Conservancy held a workshop in Hobart earlier this year involving salmonid and mussel producers, recreational fishers, indigenous and tourism representatives and other research and environmental stakeholders. While potential projects are still being developed, initial sites proposed included Triabunna, the Derwent River and D’Entrecasteaux Channel.

“Members of the Tasmanian Aboriginal community have shown interest in restoring the cultural heritage of the reefs,” she says.

Colin Creighton notes that Aboriginal middens dot the Australian coast, including Tasmania, many with enough shells in them that early colonists mined them for lime.

“Part of our vision in re-creating shellfish reefs is to reconnect various coastal Aboriginal groups with their traditional food resources,” he says. “The task of re-establishing reefs will hopefully provide work, and from this indigenous base reconnect the entire Australian community with the bounty of our coastal resources.”

FRDC Research Code: 2012-036

More information

Simon Rowe, livingshorelines@oceanwatch.org.au

Australian shellfish restoration network