Queensland research is challenging traditional understanding of fisheries habitats, with new decision-making matrices to map species’ needs

By Jo Fulwood

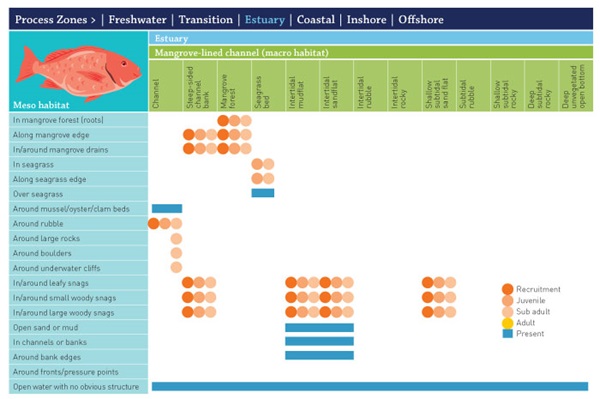

Research carried out in north-east Queensland delves into the detail of habitats that tropical fish species depend upon at different stages of their development. To do this, the researchers developed life cycle–habitat matrices to help better identify and protect areas that are crucial.

While significant research has previously been undertaken on the habitats of adult fish – the age at which they are most targeted by fishers – little has been known about other habitats tropical fish might need to progress through their life cycles.

Researchers at James Cook University have used advanced underwater video sampling over three years in the Hinchinbrook region of north-east Queensland to uncover the specific characteristics and features important to different species of fish at different points in their life cycles. Using this information, they have developed summary diagrams (or matrices) that highlight the value of critical ecological areas to the survival of particular tropical fish species of north-east Queensland.

Project co-author Marcus Sheaves says the FRDC-funded research is the starting point to understanding the many and varied habitats required by tropical fish throughout their life cycles, and the importance of maintaining the integrity of these habitats to ensure each species survives in the future.

For instance, little had been known about the use of deep-water estuary habitats by fish.

“We now know that particular deep-water habitats harbour large numbers of juveniles of important food fish, such as Golden Snapper (Lutjanus johnii).” Although this had been observed by anglers, it had not been scientifically verified.

“This research now gives us a way to record this critical information and make planning and research decisions about the numerous habitats this fish occupies throughout its lifetime,” Marcus Sheaves says.

Decision tools

The matrices, used to summarise the use and requirements of different habitats by specific species, will allow both experienced and non-experienced decision-makers to identify the most vital habitats to conserve, replace or remediate. Marcus Sheaves says managers can use the framework to make decisions about coastal and estuarine regions based on data, not guesswork or public perception.

“A manager can use our matrices to help differentiate between different scale habitats rather than just considering the area as a whole.

“If we don’t have the full story, almost invariably we make the wrong decisions and this lack of knowledge has seen the collapse of commercial fisheries in many areas around the world where there hasn’t been that understanding of the entire life cycle and the interconnecting habitats required to protect every stage of the fish life cycle.”

“While there are still significant gaps in our research, we have now identified a way, or a framework, that can allow anyone in a decision-making capacity to ascertain which habitats, large or small, are important for certain tropical fish species to thrive,” he says.

Significantly, the research could provide information necessary to protect key fisheries habitats without the need to lock away productive fishing areas by unnecessary zoning. It could allow managers to make decisions more rapidly and with more certainty, and help developers allocate money more accurately and effectively.

While the practical application of the framework is still some time away, Marcus Sheaves says ultimately the tool will ensure research dollars and repair funding are appropriately targeted.

“This work also provides the information needed to populate coastal habitat maps and classification schemes, which, in turn, will be key contributors to improved management outcomes,” he says. The research is also expected to help provide more accurate estimates of the extent and nature of habitat loss in the northern Queensland region.

Complex developmental stages

The research highlights that not all inshore tropical fish species use the same nursery areas, emphasising the danger of conducting large-scale works – such as dredging in coastal areas – without a complete understanding of the life-history values of these areas.

The research has underscored the importance of the nursery mosaic, meaning each species requires numerous different habitats at each different stage throughout its life, most of which are not interchangeable.

“Estuarine and coastal areas act as components of an interrelated nursery mosaic for many species, with different nursery values often contributed by many different macro-habitat components, such as rocks or woody debris,” Marcus Sheaves says.

“This underlines the importance of the whole interacting mosaic and the connections among its components.” He says the study also uncovered a clear distinction between early-juvenile and late-juvenile habitat-use patterns.

“In general, early juveniles often appeared to be concentrated in a single, specific habitat type, while late juveniles were more evenly spread between three or four habitats,” he says.

“A habitat, such as a mangrove habitat or an estuary, is a general term, and we need to drill down and understand which specific parts of these larger areas are important for these tropical fish species at certain stages of their life.”

Habitat redefined

The research challenges the broad use of the term ‘habitat’, basing its summary diagrams or matrices on four different zones.

Process zone × meso-habitat matrix for the Mangrove Jack (Lutjanus argentimaculatus).

Process zone × meso-habitat matrix for the Mangrove Jack (Lutjanus argentimaculatus). Source: Marcus Sheaves

Process zones refer to the gradient of overlapping environments from freshwater to offshore that have particular sets of physical conditions and resources.

Macro-habitats are large, homogenous units within the seascape, such as mangrove forests, seabeds and sub-tidal channels, that are considered at a scale of tens to hundreds of metres.

Meso-habitats are the functional components of a macro-habitat. For example, a mangrove forest could be divided into subdivisions based on horizontal spatial arrangements or even into vertical categories such as substrate, roots, trunks and leaves.

Finally, micro-habitats are classified as subdivisions of meso-habitats, providing a more detailed understanding of the requirements of each species of fish within each zone.

Marcus Sheaves says under-protecting these habitats can have catastrophic effects on fish populations, but the reverse is also true when a blanket approach to ecological protection takes place, having a significant impact on many user groups.

In southern Australia, loss of connection to key habitats has contributed to reductions in catches in the Coorong fishery at the mouth of the Murray River to well below 50 per cent of historic levels.

In some Queensland catchments, construction of barriers has seen marine fish excluded from as much as 80 per cent of coastal wetlands. The development of this framework will allow greater ability to direct resources to the most critical habitats, Marcus Sheaves says.

FRDC Research Code: 2013-046

More information

Marcus Sheaves, marcus.sheaves@jcu.edu.au