An international leader in sustainable fisheries research had two key messages for producers at the recent Seafood Directions conference in Brisbane – that intensive fisheries management improves stocks but climate change and pollution are major challenges.

By Brad Collis

An international authority on fisheries sustainability says tighter management is working, where it exists, but that it is only a partial solution to the global fisheries challenge.

Professor Ray Hilborn from the University of Washington’s School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences and Center for Sustaining Seafood was the international keynote speaker at the recent Seafood Directions 2022 in Brisbane.

Professor Ray Hilborn speaks at Seafood Directions 2022

Among his key messages were that fish stocks are increasing where fisheries are intensively managed, but that impacts from climate change and pollution present the greatest pressure.

Professor Hilborn said fisheries can and are being sustainably managed. However, producers and authorities have to contend with the impact on marine environments of climate change and pollution, especially contaminated run-off from land-based industries such as agriculture.

Summarising the global position, Professor Hilborn said databases were now established on at least half the world’s fish stocks to support fisheries management. These showed that stocks that were once declining have been increasing since 2010.

He said Europe, West Africa, America, and Japan had good data, but the global picture was missing scientific assessments in South-East Asia.

“The general opinion on the status of fish stocks in South-East Asia is that they are poor,” he said. And he said fish stocks in the Mediterranean were still suffering for all species except bluefin tuna.

“Even in well-managed countries there are some fish stocks in poor condition,” he adds.

Complex picture

The hidden complexity in this overall picture was that some places had not been overfished, some were overfished and now recovering, and some continued to be overfished, Professor Hilborn said.

He made the further point that managing consequences and responsibility was too easily shifted from country to country.

For example, he said the US was becoming increasingly restrictive, so less fish were being caught from US waters, and instead, more were being imported from countries where fisheries were not managed.

Professor Hilborn’s research focus is on building data bases that allow fisheries management to be measured and analysed. His laboratory contains data on the biological status and history of more than 500 major fish stocks that constitute about 40% of the global catch.

His university centre also studies the role of fish in the global food system and the comparative environmental cost of different food production systems.

Healthy people, healthy planet

In pushing the case for greater effort to make all fisheries truly sustainable he said capture (wild catch) fisheries provide nutritious protein for humanity at a comparatively low environmental cost.

Comparing wild catch fisheries to conventional land-based farming, he said protein from fish didn’t come with the same environmental costs, such as water pollution, pesticide and antibiotics residues, soil erosion and loss of biodiversity.

He described seafood as a healthy animal-sourced protein that could be enjoyed without draining life from the soil, drying up rivers, polluting the air and waterways, causing the planet to warm even more, and plaguing communities with diabetes, heart disease and cancer.

Professor Hilborn and members of a panel that followed his presentation, covered the role and impacts of marine conservation areas which have allowed a more controlled-scenario assessment of threats faced by different habitats and species.

Professor Hilborn spoke about his research on state-managed waters off the coast of California, where 124 marine parks cover 16 per cent of the three nautical mile coastal zone. In these areas, the only fishing allowed was angling (commercial and recreational), pot fishing for crabs, diving for sea urchins, and limited purse seining for sardines and squid. There was one small area where trawling was allowed.

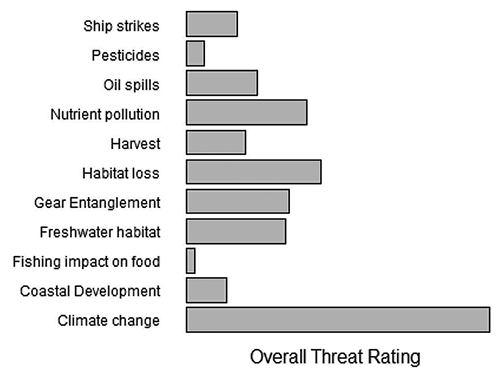

He said an analysis of threats and their severity for key species and habitats including kelp forests, reefs, salt marshes and seagrass beds, showed that climate change far exceeded every other measurable threat in this region.

The next most severe impacts were from nutrient pollution, ship strikes (for whales and turtles), gear entanglement, loss of freshwater habitats and oil spills. By comparison, actual fishing activities barely scored.

Source: How to sustain food from the seas while protecting marine ecosystems, presentation at Seafood Directions 2022 by Professor Ray Hilborn, University of Washington, School of Aquatic and Fishery Sciences.

Professor Hilborn said all these threats were “solvable problems” but would need many divergent groups working together.

He made the point that as damaging as climate change is for the environment generally, there were some winners. He said the Bristol Bay salmon fishery in Alaska, for example, had been breaking harvest records in recent years.

Broadly speaking, Professor Hilborn said solutions to the many and varied threats to different fisheries and habitats needed more local management rather than blanket management across states or countries. To this end, he said there was an important role for Indigenous communities who had long and enduring knowledge of their fisheries.

Call for unified voice

In his address to the conference, Professor Hilborn also cautioned against seeing aquaculture as a stand-alone alternative to wild catch fisheries.

Rather, he said the seafoods sector needed a unified position and voice. “Commercial fishing, the aquaculture industry, government, NGOs and the public all want the same thing – sustainable food and healthy oceans,” he said.

“We achieve this by agreeing on goals, evaluating threats and identifying the appropriate action using science-based analysis while recognizing that fisheries management is primarily people management.”

Professor Hilborn’s address was followed by a robust panel discussion during which the CEO of the Aboriginal Sea Company Robert 'Bo' Carne welcomed Professor Hilborn’s acknowledgement of the importance and value of traditional knowledge.

“Aboriginal people didn’t just watch the tide go in and out for 60,000 years,” Mr Carne said.

Mr Carne said Indigenous people learned and shared information about how the sea works, developing a true and full understanding of their environment. He called for more genuine engagement with Indigenous fishers and to include them in decision-making.

Director of Blue Policy & Planning with the Blue Economy CRC, Angela Williamson, spoke similarly of the importance of information sharing throughout the sector and the need to respond to consumer expectations for true sustainability, not just compliance.

Head of Minderoo Foundation’s Sustainable Fisheries Program, Dr Chris Wilcox, echoed this with a warning about a potential consumer backlash in Australia against illegal seafood imports from South-East Asia and the need to help neighbouring countries meet sustainability standards.

He also said Australia had its own work to do, particularly the need to reduce bycatch. He said this was largely why Australia did not score well on the foundation’s global fishing index released last year. Dr Wilcox said Australia had a reasonable proportion of species that were managed sustainably, but it rated poorly because of the amount of catch being discarded as it comprised species not considered marketable.

All panel members agreed on the need for improved communication across the sector, and with consumers, and the need to be transparent about sustainability targets that were not being met so they could be addressed.