New FRDC research seeks to understand why jellyfish blooms are persisting in the Hawkesbury Estuary – a significant disruption causing financial distress for commercial trawl and mesh fishers working in the river.

By Dempsey Ward

The Hawkesbury Estuary, a vital artery for Australia’s commercial trawl and mesh fishing sectors, are facing a slimy issue: jellyfish blooms.

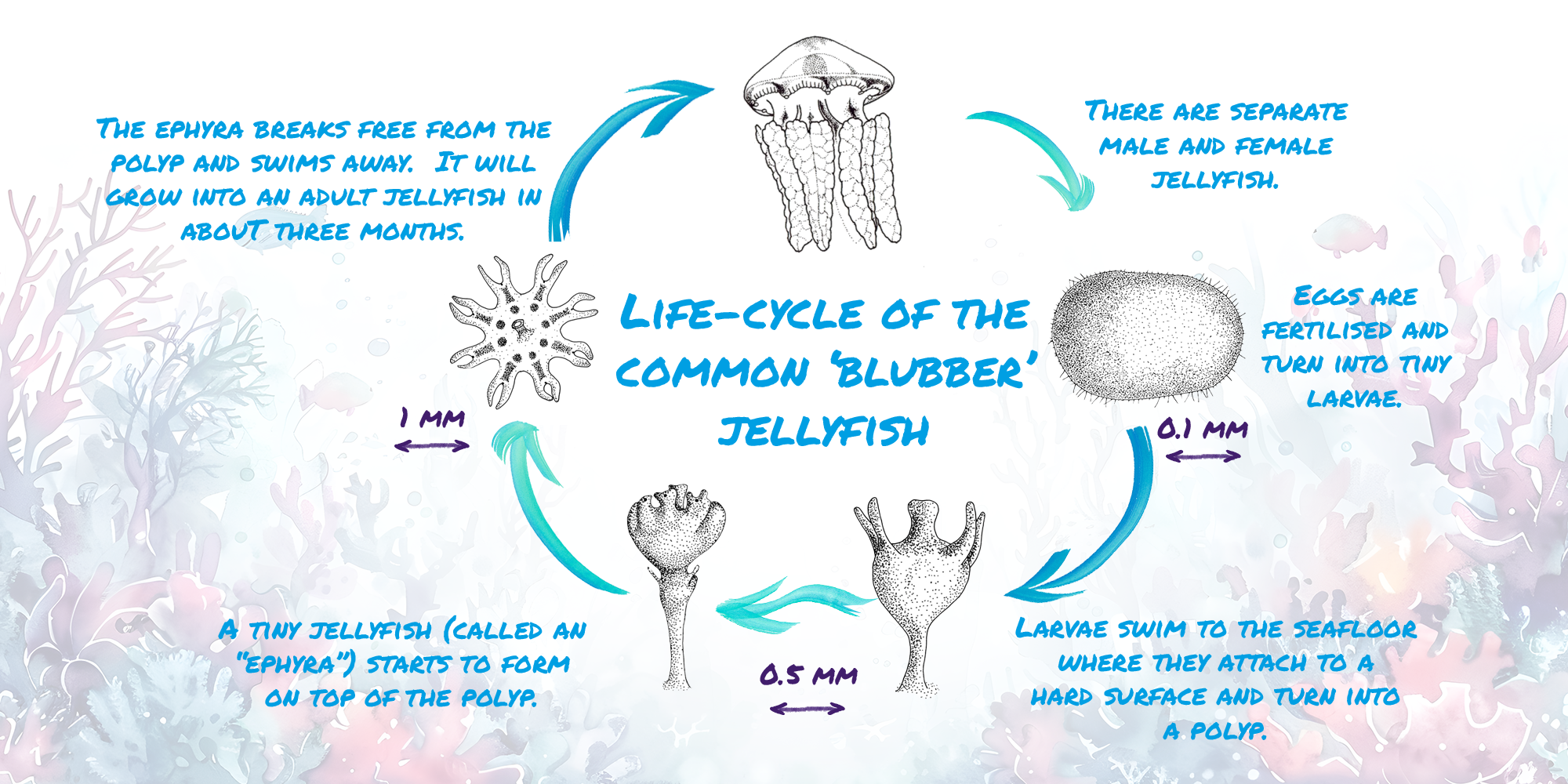

Jellyfish blooms are events where thousands of jellyfish appear both on and below the ocean surface in vast patches across the ocean. Typically, these blooms are controllable by trawl fishers using exclusion devices, called ‘blubber chutes’.

However, the proliferation of blooms, particularly those involving the Blubber Jellyfish (Catostylus mosaicus), have reached such extensive and enduring levels that fishers are finding themselves with limited viable areas free of jellyfish to deploy nets.

These polyps can spawn thousands of ephyra’s, causing major disruptions to mesh fishers when persistent and widespread.

This is causing significant financial impact for fishers, prompting some to explore alternative means of livelihood to sustain themselves.

Commercial fishing within the Central Coast region, where the Hawkesbury Estuary is located, was estimated to contribute $82 million in revenue per annum, and approximately 490 full-time jobs to the local economy as found in a previous FRDC Project.

Speculation on what, where and how these population blooms are occurring has become part of many conversations for both researchers and fishers involved in the estuary.

A vital component

Essential to any great research project is stakeholder consultation and collaboration, and this FRDC project is no exception.

The project has conducted its first workshop, with the aim of getting everybody with knowledge about jellyfish and the estuary to discuss and share their insights. The workshop group included estuary fishers with decades of experience, water quality managers, and jellyfish researchers.

“It was a knowledge exchange,” says FRDC Extension Officer for New South Wales, Kris Cooling. “The project team did an excellent job of making sure fishers with an extensive knowledge of jellyfish in the Hawkesbury estuary, over many decades, were part of the discussion.”

The main topics discussed included the possible drivers for the jellyfish blooms and potential short- and long-term solutions for removing jellyfish.

Fishers were also given a map which they could draw on and point out where they had been seeing the blooms – a vital component of the research project.

Even after the workshop, the dialogue continued, with Kylie establishing an important list of stakeholders, from whom she can share and receive information related to the estuary. She believed this was particularly helpful during the recent floods, as she could get feedback from the fishers much quicker, rather than setting up another workshop.

“This swift exchange of information is crucial for navigating the future challenges and opportunities of the project and the estuary,” Kylie states.

Second serving

While no technical solutions for reducing the bycatch of jellyfish were presented, some fishers see a potential silver lining – harvesting the jellyfish itself.

Globally, around 300,000 tons of Jellyfish are harvested each year. Studies have pointed to jellyfish being a viable substitute for traditional proteins with minimal intake of carbohydrates and saturated fats. Collagen, a prominent feature in Jellyfish’s tissue, is also an emerging health market.

“Hurdles remain,” Kylie quickly pointed out. “Establishing a sustainable harvest strategy and ensuring economic viability are crucial steps before this alternative becomes an opportunity for estuary fishers.”

The future of the Hawkesbury estuary that is home to many trawl and mesh fishers, is one of optimism. The project is aiming to unravel the mysteries of the Blubber Jellyfish to help chart the course for a sustainable and thriving fishery.

FRDC Project 2023-036 is a collaboration between Griffith University, the University of New South Wales, James Cook University, Hornsby Council, and Hawkesbury fishers.

Related FRDC Project

2023-036: Understanding drivers of jellyfish blooms in the Hawkesbury estuary