More sophisticated approaches to fishing and aquaculture research are combining public and private-sector capabilities, while striving to find the balance between fundamental science and industry-specific needs

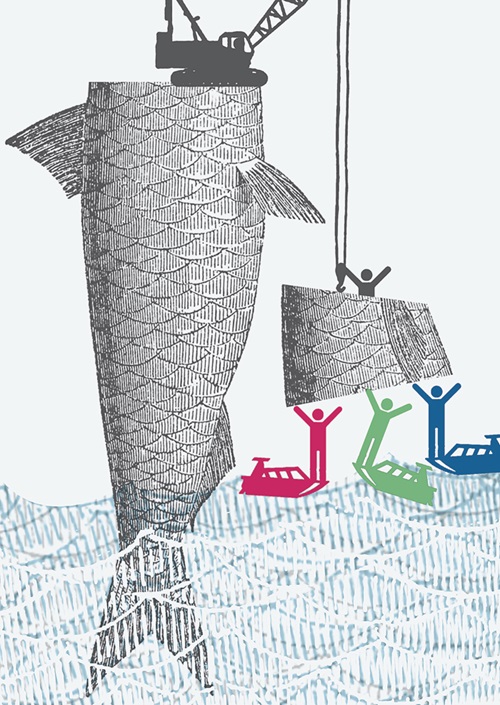

Illustration: Justin Garnsworthy

Illustration: Justin Garnsworthy By Karin Derkley

In the past five years there have been some significant changes to Australia’s fishing and aquaculture research sector. Governments have streamlined their operations, offset by an expansion of capability in universities and private enterprise.

Between 2008 and 2013, national investment in fisheries research was somewhat stagnant (Figure 1) which, if considered in real terms, represents a decrease, confirming that scientists in the fisheries sector are being asked to do more with less.

In 2009, an audit of the wild-capture and aquaculture industries’ research capability (both human and built resources) was commissioned and funded by the Strategy Governance Committee that oversees the development of the National Fishing and Aquaculture RD&E Strategy.

This study was conducted by RDS Partners and was repeated again in 2013. Most responses were from government agencies, so private-sector capabilities are not well represented.

.jpg?h=334&w=700&la=en&hash=81B30F1C86D4AB34798CD0D76B4C2C91FB992A01) Figure 1 Investment by key national research providers 2004-05 to 2012-13.

Figure 1 Investment by key national research providers 2004-05 to 2012-13.Comparison between the two studies was only done for those institutions that responded to both surveys, so results must be interpreted with this in mind. Overall, there has been minimal change in capability between the two study periods (approximately a two per cent increase).

However, state research agencies in Queensland, Victoria and South Australia all reported capability reductions of 10 or more positions, with New South Wales reporting a reduction of slightly less than 10 positions.

Director of the private agency IC Independent Consulting, Steve Kennelly, was previously Chief Scientist of the NSW Department of Primary Industries and director of fisheries research.

He says that in the past two years there has been a significant movement of government fisheries scientists into the private sector.This includes his own move from government to private consulting in 2013.

“As state departments of primary industries have reduced the numbers of fisheries scientists, many of those scientists have decided (for various reasons) to join the private sector. Mostly this involves the need to earn a living, but also the desire to continue using their substantial expertise and experience in fisheries science and management,” he says.

Having made the move into the private sector he says there are benefits, including greater freedom and flexibility in choosing projects, and fewer of the constraints that often affect government scientists. Benefits for clients include lower costs as a result of lower overheads.

Duncan Souter, who helped to establish the Asia–Pacific branch of global marine consulting company MRAG in 2008, says private companies are particularly well placed to deliver services that are not traditional strongholds of the public sector.

Before joining MRAG, he spent 16 years with the Queensland Seafood Industry Association, followed by three years as an adviser to the Australian Minister for Fisheries.

As chief executive of MRAG Asia Pacific, Duncan Souter says the business provides a range of services including resource, economic and environmental assessments. One advantage of being part of a private agency is building experience and moving across a number of jurisdictions.

“One week we’ll be working in Western Australia, the next we’ll be in Micronesia.”

He says the knowledge and expertise the firm gains from each project feeds into others.

Responsiveness

A private agency such as MRAG is able to quickly bring together the most appropriate team of people for a particular project or task. “We do a lot of subcontracting and with the networks we have we can always find the best and brightest for the specific needs of each project.”

Currently conducting a best practice review of Queensland’s fisheries, MRAG has brought into its team a former CEO of the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA), a finance, economics and seafood-supply-chain expert from New Zealand, and a former chief science adviser to the US National Marine Fisheries Service.

However, he says that while more and more private research companies are emerging to conduct specific research in particular areas, there is still an important place for publicly funded research.

“There are world-class capabilities in public agencies and we have some very close interactions with public agency staff.”

Kyne Krusic-Golub of Fish Ageing Services.

Kyne Krusic-Golub of Fish Ageing Services. Photo: Fish Ageing Services

As a researcher who has also worked on both sides of the public–private fence, Kyne Krusic-Golub says private providers have a very high level of accountability to their clients.

He worked with the Victorian Department of Primary Industries’ Central Ageing Facility for 14 years before the centre was rationalised in 2008, narrowing its services to only core Victorian fish species.

He and fellow scientist Simon Robertson took the initiative to establish Fish Ageing Services Pty Ltd to fill the gap in services no longer being provided by the department.

“We had those skills so we were able to take on [the department’s] former clients.”

He says that with no department manager or government organisation to pass the buck on to, he has a greater sense of responsibility and accountability to his clients and their needs.

“We are wholly responsible for providing that service and we are completely answerable to our clients.”

As a private agency, Fish Ageing Services has been able to provide clients with a more cost-effective service, partly because of the lower overheads.

“We run a small staff, and our equipment was not too expensive to set up and maintain. So we are able to do the work more cheaply and efficiently and pass on the savings to our clients.”

Critical mass and collaborating

Research by public agencies is built on a long history that often goes back decades, providing a rich source of data and expertise as well as linkages across the many areas of knowledge that are relevant to fisheries industries, says Caleb Gardner, an associate professor and program leader for fisheries at the Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies (IMAS) at the University of Tasmania.

His department is not averse to using private consultants where required. IMAS used economic data sourced from agricultural economic research company EconSearch to feed into its long-range economic survey work for the use of fisheries management in Tasmania and SA.

“It was very sophisticated modelling and EconSearch managing director Julian Morrison is very good at discussing economic processes,” Caleb Gardener says.

But while private researchers are good at filling in the gaps, Caleb Gardener says that he doubts whether bigger projects could be achieved without the critical mass that can be achieved in the public area.

“We are able to collaborate easily across large areas. For instance we work with people in CSIRO and at other universities. We tend to be less interested in where the other researcher is from than whether they have expertise in areas that are relevant to the project.”

Steve Kennelly from IC Independent Consulting.

Steve Kennelly from IC Independent Consulting. Photo: Chris Lane

Gavin Begg, SARDI.

Gavin Begg, SARDI. Photo: SARDI

In SA, the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) delivers a breadth of expertise that cannot be matched by the private sector, says research chief of SARDI’s Aquatic Sciences Gavin Begg.

“At the end of the day, most of the private businesses arefairly small and usually built on one key person, whereas we have expert teams in a whole lot of areas. We have a suite of people that we can draw on in terms of their skills and expertise.”

Given that fisheries are operating within a public natural resource, having a research agency that can balance the needs of all sectors using that resource is essential, he says.

“SARDI acts not just for government but also for the other sectors – commercial, recreational, community and indigenous – whose interests may sometimes conflict. What we provide is a vehicle of independence to deal with all those sectors to ensure their interests are balanced out.”

The extent to which state research agencies have outsourced research varies. WA’s Department of Fisheries chose to keep all its fisheries research capacity in-house when it conducted a review in 2010 into how fisheries research was best managed in the state.

The decision to do that, rather than splitting it off into a stand-alone agency or outsourcing research to the private sector, was based on the effectiveness of management, says research director Rick Fletcher.

It was decided that keeping the three key components of fisheries management – research, policy and compliance – in-house was essential for efficient and effective management of natural resource systems, he says. “If you take out one of those three legs of the ‘management stool’, it falls over.”

The free flow of information among the various divisions has been beneficial for management outcomes, he says.

“If you need to find information from someone else in the department, or you identify an issue of relevance to other groups, there is generally no need for a formal process so this exchange can occur rapidly. This means management actions and shifts in research priorities can be initiated in a very timely manner.”

This integrated arrangement also means that the department takes long-term responsibility for all past work, irrespective of when it was done.

The need for balance

From an industry association perspective, Renee Vajtauer, executive officer of the Commonwealth Fisheries Association (CFA), questions how responsive public research agencies are to the needs of industry in their research priorities.

Moving to the CFA from her previous role as executive officer of Seafood Industry Victoria, she says research at state level tends to be much more industry-driven.

Priorities at the Commonwealth level are more likely to be driven by government processes, such as through Management Advisory Committees (MACs) and Resource Assessment Groups (RAGs).

“There needs to be evidence that the research proposals have engaged industry through adequate consultation, from the expression of interest stage to the final report,” she says. “Preferably, I would like to see more research projects owned by industry.”

Renee Vajtauer believes that the private sector is as capable of carrying out the research as the government sector. “And if they can do it more cost-efficiently and with the same outcome, I think that works better for the industry.”

However, Gavin Begg says that there are concerns regarding the objectivity of private research that is purely industry-driven. “A number of consultants have been seen as industry-available, and some might be seen as less objective than others. Whereas, what you expect from a government organisation is independent and objective science.”

This is an issue that also concerns industry representative Martin Exel, who is general manager of environment and policy at Austral Fisheries and who also holds several industry representative positions, including past chair of the CFA.

He is concerned about the steady decline in publicly funded research into fisheries, and the assumption that industry will carry the burden of funding private research into their operations.

Collaborative research between industry and private and public research agencies can work well, he emphasises, citing as an example work done over the past couple of years by his own company and Australian Longline Pty Ltd into the status of Patagonian Toothfish (Dissostichus eleginoides) stocks.

This industry collaboration has helped inform quotas and management strategies and has involved the FRDC, IMAS and AFMA, as well as the World Wildlife Fund and the Australian Antarctic Division of the Department of the Environment.

“That was a truly collaborative outcome. We all paid for it, so we all had a sense of ownership and were able to closely monitor the milestones,” Martin Exel says.

However, while the Patagonian Toothfish industry was prepared to provide funding for the laboratory equipment and pay for fish ageing services and fisheries modelling, he is concerned this has triggered an assumption that industry will continue to fund these government research obligations.

“We know there are limitations of how much government can pay, but it is scary when this is turned into a regular thing. There needs to be a base standard of government research into fisheries and the marine environment.”

While enjoying his move into the private sector, Steve Kennelly’s 25 years of experience with government agencies means he is highly attuned to the responsibilities of managing publicly owned resources such as fisheries.

“Fisheries are managed by government on behalf of the whole community – it is a core function of government to do this. Most of the researchers previously based at Cronulla were working on wild-capture fisheries resource assessment, and their work cannot easily be picked up by the private sector.

"Private businesses are usually not set up to do long-term stock assessment work in the way that governments are, so it is crucial that governments maintain the capacity to manage these public resources effectively and sustainably.”

Steve Kennelly says the emerging mix of public and private research is providing new opportunities and efficiencies for industry, particularly for the aquaculture sector – where projects are much more driven by the needs of private enterprise.

However, for wild fisheries, the public expects governments to maintain sufficient scientific capacity to manage these resources for current and future generations.

Photo Caption (above right):

Austral Fisheries staff were part of a collaborative research project gathering information about Australia’s Patagonian Toothfish Fishery, around Heard, Macquarie and McDonald Islands. Austral conducted extensive annual scientific surveys to closely monitor the toothfish populations and worked with government observers to monitor practices, fish biology and conduct continuous stock assessments.