A new oyster aquaculture industry is on the verge of large-scale commercialisation in South Australia

Xiaoxu Li of SardI aquatic Sciences.

Xiaoxu Li of SardI aquatic Sciences. Photo: SARDI

By Gio Braidotti

The sensitivity of cultured oysters to new and exotic disease outbreaks has revealed a critical weakness in the way this lucrative industry is structured in Australia. Lack of diversification means the livelihoods of too many growers are based on a single, disease-prone species.

South Australia relies exclusively on Pacific Oysters (Crassostrea gigas) to sustain a $40 million oyster industry. Aware of the risks, some growers have begun exploring the feasibility of cultivating the Native Oyster (Ostrea angasi).

Research at the University of Sydney has confirmed the Native Oyster is resistant to Pacific Oyster Mortality Syndrome (POMS), a disease that has been decimating production internationally and in Australia (see page 26).

In Coffin Bay, on the Eyre Peninsula, Pristine Oyster Farm’s Brendan Guidera considers the Native Oyster a premium seafood. “What interests me is their flavour and fat,” he says. “They are on par with the famous Belon oysters from France – the world’s most expensive oyster.”

Keen to run grow-out trials he and other farmers, particularly on Kangaroo Island and the Eyre Peninsula, sought the assistance of the South Australian Research and Development Institute (SARDI) to continue to develop hatchery and broodstock technology for Native Oyster to supply industry with spat and to form the basis of a program of genetic and further technical improvements.

SARDI shellfish aquaculture geneticist, Xiaoxu Li says the main difficulty is that unlike Pacific Oysters, Native Oysters do not release millions of seed from which hatcheries can produce spat. Rather, they rear a much smaller number of young – about five times less than Pacific Oyster – in their mantle cavity.From there, the fertilised eggs develop into shelled larvae before finally being released into the surrounding water.

SARDI production capacity over the past four years has totalled four million Native Oyster spat – one million per year. This is made available to growers by open tender after disease clearance assessment, usually some time between February and May each year.

“Diversification is critical to manage potential business risks from disease,” Xiaoxu Li says. “The development of Native Oyster aquaculture would be an ideal strategy to mitigate impacts from POMS when it occurs in SA.”

Recent advances include the ability to store sperm (for year-round spat production) through the development of a cryopreservation technique and optimisation of the early (or ‘white’) larvae rearing system.

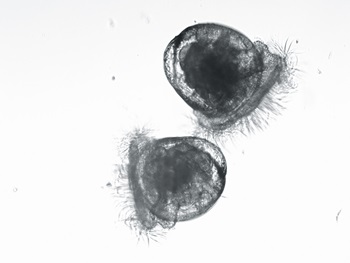

Larvae of Native oyster (ostrea angasi) 14 days after strip spawning (black larvae) produced in culture in South australia, thanks to research led by Xiaoxu Li.

Larvae of Native oyster (ostrea angasi) 14 days after strip spawning (black larvae) produced in culture in South australia, thanks to research led by Xiaoxu Li. “Preliminary results from trials with our prototype rearing system were promising, with fully shelled (or ‘D-larvae’) produced,” Xiaoxu Li says. “This is essential to the long-term development of the industry. In addition, the optimisation of a chemical metamorphosis-induction method has now achieved more than 80 per cent metamorphosis and survival.”

Farmers such as Brendan Guidera have been using the spat to test grow-out methods while also providing SARDI with fertile broodstock. He says farming methods optimised for intertidal oysters, such as Pacific Oysters, are not ideal for the Native Oyster, which grows slowly and is prone to dying, especially in high heat.

However, if left too low in the water the baskets and oysters foul up with weed and parasites.

“I think the most likely way to viably farm Native Oyster is to grow them to market size sub-tidally in baskets and finish them off inter-tidally using the adjustable longline method,” Brendan Guidera says.

“The shape and flesh composition is improved, and the abductor muscle is also strengthened, giving them a much better shelf life.”

While the threat from POMS is the major reason cited for trialling Native Oysters, Brendan Guidera says they also present new market opportunities. During tastings at recent ‘oyster and wine’ events in SA, about three-quarters of people preferred the Native Oyster to the Pacific Oyster despite never before tasting a Native Oyster.

Consumers reported preferring the firmness and chewiness of the Native Oyster flesh and the long-lasting range of changing aftertaste.

Another option Brendan Guidera is considering is to sell Native Oysters to Europe, where they are very highly regarded.

“We will be sending a trial shipment in 2015. We also sell some direct to some Australian restaurants.”

Pristine Oyster Farm has been operating for more than 20 years, with leases at Cowell and Coffin Bay. It produces about six million Pacific Oysters a year, about 65 per cent of which are exported, mainly to Hong Kong.

FRDC Research Code: 2013-044

More information

Professor Xiaoxu Li, xiaoxu.li@sa.gov.au