A new guide shows how to benchmark the performance of Australia’s commercial fisheries to improve understanding of their economic productivity.

By Brad Collis

A recently completed Fisheries Research and Development Corporation (FRDC) project shows that productivity analysis of Australian fisheries can be a valuable indicator of economic performance in fisheries and an important support for fisheries management.

A guide produced as part of the project, Using Productivity Analysis in Fisheries Management shows how productivity analysis can support fisheries management. This includes identifying commercial fisheries that are not achieving their potential, plus helping evaluate the economic effects of changes to fisheries management.

The guide is one of the key outputs from the FRDC-funded project, ‘Measuring, interpreting and monitoring economic productivity in commercial fisheries’, which was led by University of Adelaide resource economist Dr Stephanie McWhinnie.

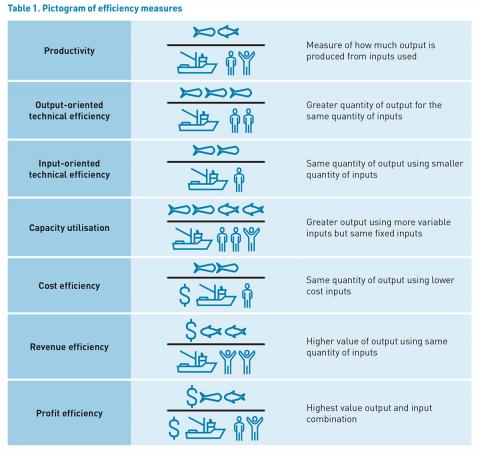

Extract pictograph from guide

Stephanie says evaluating the economic performance of fisheries is crucial for effective fisheries governance, however this has been hampered by limited data.

The project team set about finding ways to use anonymised data that is already provided by fishers as well as looking for other data that might help address more nuanced questions about fisheries governance.

The guide uses three Australian case studies to illustrate how productivity measures can be used to evaluate and monitor fishery performance. The focus is on using ‘technical efficiency’ – a measure that highlights the gap between existing and potential productivity. This measure can indicate shifts or changes over time that might be going unnoticed due to lack of data or analysis.

“There are many different metrics we could use, but the advantage of technical efficiency is it can be calculated from quantity data of catches and inputs. This is more readily available than value data in most fisheries,” says Stephanie.

One of the case-study fisheries was the Queensland Spanner Crab Fishery, which had no direct economic data, but there was a trove of quantity data from logbooks. Following management changes two decades ago, this fishery is today rated as sustainable. However, examination shows that gains are yet to materialise from an economic perspective.

“Its technical efficiency – the difference between current production and what could be produced if every fisher was performing at the same level as the top performing fishers – is low on average,” says Stephanie.

She points out there may be many reasons for this, including not every fisher being motivated by maximising profit. ‘Way-of-life’ considerations and historical and management features, also come into play in many fisheries.

Identifying unrealised productivity potential, she says, is about alerting fisheries managers and industry bodies to a deficiency so they can act upon if they want to. She says it is important to keep in mind that the technical efficiency indicators are averages for a whole fishery or whole fleet, not individual operators.

Stephanie says an example of a fishery with relatively high technical efficiency is the Commonwealth Northern Prawn fishery. Using a long history of economic data, the study showed that technical efficiency correlates highly with measures of economic profit in this fishery where the output market is quite uniform.

The Northern Prawn Fishery was one of the case studies for the project on benchmarking the economic performance of Australian fisheries.

“The high level of efficiency was also assisted by the licence buy-backs program in 2007, so it is a good example of the influence of appropriate resource management.”

The South Australian Spencer Gulf and West Coast Prawn fisheries also exhibited relatively high average technical efficiency, but this isn’t such a strong predictor of economic performance, she says.

“The cooperative management nature of these fisheries means there are minimal differences in quantities of inputs and outputs, but there is larger variation in prices for outputs and costs of inputs than in the Northern Prawn fishery.”

Data is the key and Stephanie says researchers are keen to identify other sources of Australian fisheries’ data, wherever it exists. She notes that it is well recognised that data collection comes at a time-cost for fishers and hopes fisheries managers and industry can work with researchers to maximise the potential of existing data.

“What we’re doing is working to build a picture of the economics of fisheries and providing the managers and operators of those fisheries with this knowledge. They can then interrogate that information and ask, for example, ‘why is technical efficiency in our fishery low?’, ‘do we need to address this?’ or ‘our fishery is biologically sustainable but is it economically sustainable?’

“Investigating these sorts of questions might show a situation is cost prohibitive, or uneconomic, to address. That’s fine, but at least we have provided a basis for asking the questions.”

The project drew on more than 30 years of Australian and international research and the team comprised economists, analysts and fisheries managers from the University of Adelaide, CSIRO (Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation), the Australian Bureau of Agriculture and Resource Economics and Sciences, BDO EconSearch, Primary Industries and Regions South Australia, and the Queensland Department of Agriculture and Fisheries.

More information:

- Measuring, interpreting and monitoring economic productivity in commercial fisheries

- FRDC Project 2019-026

This relates to R&D Plan Outcomes 1 & 2