Fishers and managers can make use of new national guidelines to set a clear direction and consistent approach in the development of new harvest strategies

By Ilaria Catizone

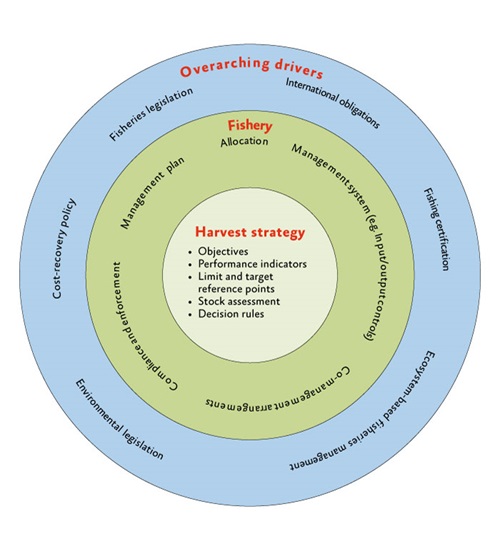

Figure 1 A schematic representation of how a harvest strategy fits within the overall fishery management framework.

Figure 1 A schematic representation of how a harvest strategy fits within the overall fishery management framework.Underpinning the high level of confidence in Australia’s fishing practices is the substantial effort put into developing the best possible policy and reporting frameworks.

One component required for good fisheries management is good data collection and reporting of stock status.

In December 2012, The Status of Key Australian Fish Stocks Reports, which involved more than 80 fishery scientists and managers, was released.

This was the first time that data from all Australian jurisdictions had been brought together in a single, consistent document for direct comparison and analysis.

Other important components of effective fisheries management include the processes for making decisions on harvests and the impact on ecosystems.

The Commonwealth fisheries bycatch and harvest strategy policy and guidelines have recently been reviewed in the process of ongoing improvement (featured on pages 10 and 11).

As with stock status reporting, harvest strategies have varied widely across Australia in their form and application from fishery to fishery and jurisdiction to jurisdiction.

The Australian Fisheries Management Forum (AFMF) – a group comprising heads of the Australian and state and territory government agencies responsible for fisheries – identified the need for a coordinated, nationally consistent approach to harvest strategy development across all fisheries management jurisdictions.

As a result, the project ‘National Guidelines to Develop Fishery Harvest Strategies’ was developed.

The project was led by Sean Sloan, director of fisheries and aquaculture policy at the Department of Primary Industries and Regions South Australia (PIRSA), and supported by the FRDC.

The aim was to establish a framework and guidelines for fishery harvest strategies that could be applied in all jurisdictions.

The new guidelines allow for the creation of harvest strategies across the full range of fisheries.

They provide practical assistance to help overcome challenges such as multi-jurisdictional, data-poor, recreational and customary fisheries that may have made it difficult to develop and implement harvest plans in the past.

Sean Sloan says harvest strategies help fisheries respond to the increased community concern about fishing harvests.

Well-designed harvest strategies ensure that catches are managed to ensure sustainability and to maximise economic performance, social outcomes and fishing experiences.

The reference points and decision-rules in a well-constructed harvest strategy ensure that catches are set objectively, using the best available science, and are less able to be influenced by external pressures.

“The existence of an effective harvest strategy ensures that fishery management agencies and key stakeholder groups think about and document how they will respond to various fishery conditions, before they occur, to provide for greater certainty and to avoid ad-hoc decision making,” he says.

In its simplest form, a harvest strategy provides a formal and structured framework to guide fishery management decision-making processes to assist in achieving fisheries management objectives.

A harvest strategy brings together all of the key elements and management functions used to make decisions about the level of fishing that should be applied to a fish stock or a fisheries management unit to maximise the likelihood of achieving ecological, economic and social objectives.

“Having a set of national harvest strategy guidelines in place helps to build consistency and a clearer understanding among all jurisdictions, by providing definitions, a common language and important contextual information for everyone to use,” he says.

“This is particularly important when a fishery straddles several different jurisdictions, each with a different approach to managing its resources.”

Although the National Fishery Harvest Strategy Guidelines are voluntary, they have been endorsed by the AFMF as a set of best practice guidelines for future ratification by Fisheries Ministers through the Primary Industries Standing Committee.

The guidelines identify the key components of a harvest strategy, the design principles that should be applied when catering to specific fisheries and the key process steps that should be followed when developing a harvest strategy.

A harvest strategy should include:

- defined operational objectives for the fishery;

- indicators of fishery performance related to the objectives;

- a statement defining acceptable levels of risk to achieving the objectives;

- reference points for performance indicators;

- a monitoring strategy to collect relevant data to assess fishery performance;

- a process for conducting assessment of fishery performance relative to objectives; and

- decision rules that control the intensity of fishing activities and/or catch.

Although the basic design characteristics are common to all fisheries, it is important to pinpoint specific issues for individual fisheries and modify the harvest strategy accordingly.

Recognising differences

To see how some existing harvest strategies stack up against the new guidelines, a few examples were documented, including for the South East Trawl Fishery (Blue Grenadier), the Southern Squid Jig Fishery, the South Australian Rocklobster fishery and the South Australian Pipi fishery.

The existing harvest strategies for these fisheries are substantially different – mostly because different levels of data are available in these fisheries. It highlights the need to tailor harvest strategies to specific fisheries. It is possible to do without perfect data or significant resources.

Blue Grenadier stocks are annually monitored through industry-based acoustic surveys, which provide estimates of biomass.

In contrast, there are no biomass estimates for the stocks of Gould’s Squid. Consequently, the Blue Grenadier total allowable catch is based on percentages of the carefully calculated unfished spawning biomass, while for Gould’s Squid, catch limits and effort triggers are defined by recent catch history.

Sean Sloan says the project showed all Australian jurisdictions apply elements of harvest strategies in varying degrees. Most jurisdictions use harvest strategies but there is little consistency in their development, application or the definitions and language being used.

At a national level, most stock assessments feeding into harvest strategies were found to be based on empirical evidence about stock status, with about 30 per cent of fisheries, species and stocks evaluated using quantitative stock assessment models.

This demonstrates that effective harvest strategies do not rely on having complex (and at times costly) mathematical stock assessment models. They can be more cost effective to construct and use.

However, it is still useful to update the quantitative assessments regularly to make sure that the harvest strategies are continuing to achieve their management objectives.

The broad principles established as part of the harvest strategy guidelines include:

- consistency with legislative objectives, including the principles of ecologically sustainable development;

- pragmatic and easy to understand;

- cost effective;

- transparent and inclusive;

- precautionary; and

- adaptive.

“Getting all jurisdictions to agree on the same guidelines was the most challenging part of the process,” Sean Sloan says.

There were national technical workshops and wide industry consultation. A project working group involved technical experts including Tony Smith (CSIRO), Caleb Gardner (the University of Tasmania), Lianos Triantafillos (PIRSA), Kelly Crosthwaite (Victorian Department of Environment and Primary Industries), Tim Karlov (Department of Agriculture, Fisheries and Forestry) and Brian Jeffriess (Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association).

The national guidelines have already informed reviews and development of policies in Victoria, Western Australia, South Australia and the Commonwealth.

South Australian Pipis a test case

Sean Sloan says the application of the new guidelines in the Pipi fishery in SA’s Coorong region has provided a postive test case for the project. Commercial fishing for Pipi in this area caters to the recreational fishing bait market and the human-consumption market.

For years, the groups focusing on these different markets within the industry had struggled to agree on a catch level for the fishery and the process for setting the catch level, and this had caused considerable angst within the industry over the key values to influence the setting of the total allowable commercial catch.

The new guidelines were used to develop a harvest strategy for the Pipi fishery.

Once the Pipi harvest strategy was finalised and adopted it took all of the heat out of the annual catch setting process and made it easy for all involved to understand the key values driving a balanced decision and reach an agreement, Sean Sloan says.

A well-constructed harvest strategy that is applied consistently can deliver significant benefits to managers, fishers and other key stakeholders.

“Knowing which criteria are used to set the annual catch quota helps fishers to make better business decisions for the future as they can predict how their catch allowance will vary in the next few years, in line with the harvest strategy,” Sean Sloan says.

When applied by Australian fisheries management agencies, the guidelines will provide greater certainty for commercial, recreational and customary fishers and other key stakeholders such as conservation groups, particularly in relation to the way in which fishery management agencies will respond when certain conditions (desirable or undesirable) arise in a fishery.

“The next step is to develop more case studies to test the practical application of the guidelines,” Sean Sloan says.

FRDC Research Code: 2010-061

More information

Sean Sloan, 08 8226 8103

sean.sloan@sa.gov.au