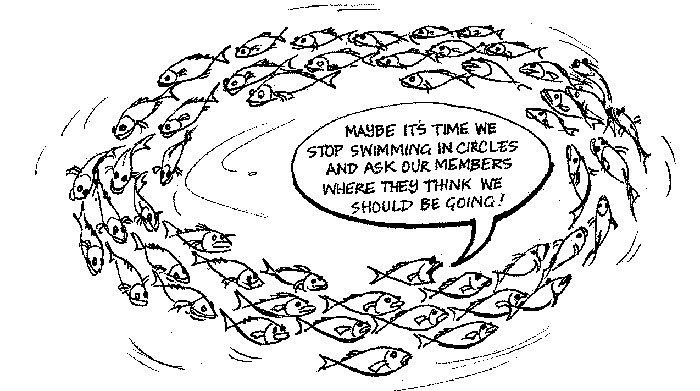

Valuing diversity and actively pursuing new members are crucial if fishing industry associations are going to survive and thrive

Illustration: Pam Walpole

Illustration: Pam Walpole By Catherine Norwood

Fishing industry associations provide an important training ground for leaders, and the health of these organisations is critical to both the sectors they represent and the industry as a whole.

A new FRDC project examines what associations can do to improve their health, at the same time bolstering the potential pool of industry leaders.

Social researcher and organisational psychologist Ian Plowman and natural resource management consultant Neil MacDonald are the investigators for the Healthy Industry Associations and Succession project.

They have conducted 68 interviews to develop 22 association case studies – 12 associations from within the Australian wild-capture, aquaculture and recreational fishing industry, four overseas seafood industry associations, and six from Australian land-based primary industries for comparison.

Ian Plowman says the decreasing number of participants in the Australian commercial fishing industry and the ageing workforce are challenges for the ability of associations to attract, train, engage and retain members. Doing so is critical to the future of the associations and industry generally.

“The recruitment of younger members into an industry and into an association is the most important work that can be done. And the task is perpetual. Without younger people getting exposure to your industry and gaining an appreciation of its benefits or challenges, cutting their teeth on small lower levels of civic involvement, there will be no future leaders and no industry to lead.”

The project interviews revealed that all associations participating suffered from an ageing membership, with too few people shouldering the load. Most struggled to attract new members, particularly younger members, and only one of the associations had a deliberate policy of leadership succession.

Only a small number of the associations had a deliberate policy of developing future leaders through allocation of responsibilities to even the newest members.

The report indicates that the average age of professional fishers, in both aquaculture and wild-catch, is over 50. The children of many professional fishers are choosing not to follow in their parents’ footsteps, and entrants from outside the industry are relatively rare.

Ian Plowman says the career options now available to young people are vastly different than those of their parents and with increasing urbanisation and higher levels of commercial education, there are fewer young role models for potential fishers from outside the industry.

New entrants in the fishing industry could also be deterred by high costs and a lack of influence once they have bought in.

“In most cases the industry buy-in costs are prohibitive. Quotas and access limitations restrict the number of licences. Retiring fishers become investors with their licences a substantial component of superannuation. Leasing of licences places all the downside risk with the lessee, rendering the venture less attractive than it would be to an operational licence-holder. And in the main, full voting members of associations need to be licence holders,” Ian Plowman says.

“Consequently, today’s operational fishers, as opposed to licence holders, may have less say in their industry than those who may no longer be actively involved in an operational sense.”

He says a common comment during the interviews was: ‘You’ll never find a happy fisherman.’While it may be part of the industry culture to complain how tough things are, such negative comments make fishing an unattractive career option.

The governance processes commonly employed by associations, such as their meeting processes, also tend not to give younger members a voice. So they disengage.

While acknowledging the many complex external factors that can lead to an industry being unattractive to new entrants, Ian Plowman suggests that the industry as a whole needs to consider the internal structural and cultural factors that restrict entry to younger potential fishers.

The research also revealed distinct differences in the nature of the wild-capture, aquaculture and recreational fishing sectors, which have specific implications for their associations.

Sector profiles

The wild-catch sector is multi-generational and follows a similar pattern to land-based agricultural businesses, with family members (usually sons) inheriting operations. Most of the member expertise is based around fishing and fishing operation issues. The ‘elder statesmen’ of the industry tend to exert a strong influence over associations, either directly or through family connections.

There is often an element of distrust because association members may be in direct competition with each other and association executives are seen as being in a privileged position to receive critical information that they can potentially use for their own benefit, as opposed to the benefit of all members.

Most of the Australian aquaculture sector is still in the first generation and is often highly dynamic and prosperous. Some operations are owned by professional investors who install professional scientists and managers.

In first-generation industries, members tend to act more cooperatively than in longer established industries, supporting each other in experimenting with a new crop or commodity.

Members are also likely to have a higher level of education than in the wild-capture sector, with more depth, particularly in the scientific field. However, this does not necessarily extend to the greater breadth of skills that may be required for the successful operation of industry associations or representational leadership.

In the recreational sector there is no connection between the vocation and avocation of members – between their employment and their hobby. This sector has a highly diverse membership of all ages.

It is more likely to have access to a broad range of expertise, and some recreational fishing organisations have specifically recruited fishers with business-related skills to assist representational associations.

Yet, like associations elsewhere, the formal structures commonly used are more likely to discourage potential younger members. So recreational fishing associations, too, struggle to attract younger members.

Ian Plowman says many wild-catch fishing industry associations began with fishers working and catching on behalf of processors, and feeling that they were not being treated fairly. As a result, they formed groups largely for collective bargaining. Membership was, and still largely is, homogenous; the skill sets of the associations are rather narrow.

But today, undoubtedly the demands upon associations have increased and so the associations need to be served by a broader base of expertise.

“Financial, scientific, legislative, corporate governance, media – every dimension has become more complex,” Ian Plowman says.

“The thing that fishers would never have talked about 10 or 15 years ago was their social licence to operate. Now it needs to be at front of mind, or public opinion will turn off access to the fishing resource.”

He suggests that looking for executive members outside the industry to bring in additional expertise is one approach that can help broaden the association’s skill set to deal with this complexity.

Money and influence

Funding the operation of associations, which are largely run by volunteers and based on voluntary levies, was an ongoing concern for most associations involved in the project.

The Australian fishing industry does not have a representative national body, which reduces its potential political clout as governments have an increasing preference to speak only with peak bodies.

“Everyone agrees there should be one, but there’s no money left,” Ian Plowman says.

“The problem is that money goes from a local association to a regional or state sector body, and then to a national sector body, by which time the money starts to run out. My suggestion – if only for discussion – is to turn this on its head.

“Fishers could form a national peak body, one that individual fishers are members of, not other sector bodies or associations. Members can then direct how funds filter down to various sectors and regions. That way, when the money runs out, it stays with the most influential level longer, rather than the least influential.”

The project has developed a series of recommendations to improve the health of associations, based on the case studies and a literature review of best practice.

Success by association

Healthy and successful industry associations incorporate many of the following characteristics:

- a clear charter describing the organisation’s purpose, which is widely promoted and reviewed annually to ensure it remains relevant to the needs of members;

- clear strategies and goals to be achieved, incorporating performance measures;

- actively pursuing and valuing of diversity in membership and among board representatives – encouraging members of different ages, background, experience and gender – to enhance creativity and innovation;

- benefits to members that make membership valuable and worth supporting with financial or in-kind assistance;

- an inclusive membership criteria that recognises the right of anyone with a direct or indirect interest in the industry to take part;

- different membership options and fee structures based on capacity to pay;

- multiple income sources to supplement membership fees, perhaps including investment income or sale of skills and services;

- a financial reserve equivalent to one year’s operating expenses as a buffer and for special contingencies;

- clearly defined roles and responsibilities for all members of the association, including its executive and committee, with performance indicators;

- distribution of responsibilities as widely as possible among members, rotation of roles, with a position-elect, incumbent and immediate past officer bearer (as mentor) for each position;

- an exit strategy for each elected position, identifying when the person elected will stand down (a maximum of two elected terms is recommended);

- split-half elections, replacing only half of the office bearers at any one time;

- a clear code of conduct for members and members of the board, with policies for the transparent handling of partisan issues or potential conflicts of interest;

- investment in capacity and skill development, including leadership skills, for both volunteer and paid staff and support opportunities to use those skills;

- active sourcing of external expertise to contribute new ideas and different perspectives,

and to add to the board’s skills; - awareness of external threats and willingness to build relationships with other organisations for collective activities such as marketing or lobbying public opinion;

- regular reviews of performance for continuous improvement, including feedback from stakeholders;

- face-to-face communication between the association and members, supported by digital and other communication channels to help engage with all members and to harness member feedback; and

- an understanding of where the association sits in the normal life cycle of organisations (growing, stable or declining) to help prepare for the next stage of the life cycle.

Sea change success for Luke

Luke Dickens has made a new career for himself at Coffs Harbour as a commerical fisher.

Luke Dickens has made a new career for himself at Coffs Harbour as a commerical fisher. By Lynda Delacey

Fisher Luke Dickens, from Coffs Harbour, New South Wales, is something of an anomaly in the commercial wild-catch sector. Most new recruits come to the industry through their family relationships. But that is not the case with him.

He is an ‘outsider’, with no family history in the fishing industry, and in just seven years he has successfully made the transition from a career as a carpenter to a commercial fisher. He has progressed from leasing to buying a fishing business and has recently upgraded his boat.

Luke Dickens says the career change was about doing work he enjoys. “I’ve always been a keen recreational fisher and often wondered if moving into fishing full-time would be an option,” he says.

In 2005, Luke Dickens was working on a project that enabled him to build some residential units.

When he sold the units he was able to buy a commercial fishing boat and lease a trap and line business that enabled him to start catching Yellowtail Kingfish and Snapper in the Coffs Harbour area. He sells his catch to the Coffs Harbour Fishermen’s Co-operative.

“It was hard at first and I often worked long hours, especially in the first few years,” he says. “I had a real gap in experience to overcome. But once I had my boat in the harbour, I formed friendships with other fishers who gave me advice when I needed it – I’m lucky the fishing community has been so supportive.”

He built his business gradually and in the first few quiet seasons would fall back on carpentry a few days a week. After a few years he had enough success to buy the business outright.

“I did have confidence from the start that this would be right for me,” Luke Dickens says. “I think it’s a good industry to get into if you’re in the right area and you have a good background knowledge of the area you’ll be fishing. I don’t know if I would have made it if I didn’t have that background knowledge – not knowing an area makes it hard.”

Seafood operations manager at the Coffs Harbour Fishermen’s Co-operative Shane Geary says he has been impressed by Luke Dickens’s success.

“It’s great to see someone coming to the industry who really enjoys it and is doing well out of it,” he says.

“The majority of fishers in this area generally come through a family business. There are a few newcomers like Luke coming into the industry but whether they’re successful or not is another thing. Luke stands out because he’s made such a fast and successful transition from his previous trade to fishing. It seems to be his true passion, which plays a huge part in his success, I think. He’s always willing to learn and has picked it up fairly quickly.”

There is an upward trend in the fishing industry in the Coffs Harbour area, according to Shane Geary.

“We have the harbour as full of working vessels as I’ve seen in the 21 years I’ve been working here. We’re actually short on moorings for working vessels at the moment, which is fantastic for the local economy and seafood consumers.”

Luke Dickens agrees that fish prices seem to be good, even if the quantities might be down slightly.

“My business is growing, and I think people always have to eat and seafood’s a healthy food, so I’m hoping the industry will keep doing well,” he says.

“The biggest challenge is the uncertainty; it makes it hard to invest.”

Contributing to the uncertainty are changes in access to fisheries resources as a result of new marine protected areas and the restructure of the NSW commercial fishing industry.

He is a member of the Professional Fishermen’s Association, which has been keeping him up to date with proposed changes through a series of local meetings.

Luke Dickens works about 40 hours a week, depending on the weather.

“It is going well enough that I now completely rely on my fishing business. I’ve upgraded to an eight-metre aluminium boat, I occasionally take on a deckhand or two, I’m paying my mortgage, and my wife and I have a new baby daughter.”

He is confident that the move was the right one for him. “I love being out on the water. Some days are harder than others, but you get that with most jobs. It’s not for everyone, but it works for me.”

FRDC Research Code: 2011-410

More information

Ian Plowman, 0417 705 489

ian@plowman.com.au