New technology and more sophisticated data systems are helping fishers and managers offer greater assurance on sustainable fishing practices

By Tom Bicknell

The increased complexity of fisheries management and greater scrutiny of the industry overall is leading to an increase in the monitoring of fishers in Australia and internationally.

The technologies that provide monitoring capacities are also becoming cheaper and easier to use. The increase in monitoring comes with mixed blessings, but the end result is greater accountability within the fisheries sector.

E-monitoring cameras.

E-monitoring cameras. Photo: AFMA

On-board observers

In July 2015 the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA) formally launched a mandatory electronic monitoring (e-monitoring) system in several Commonwealth fisheries as a reliable and more cost-effective way to verify fishers’ logbook data. Traditionally, on-board human observers have been used to verify approximately 10 per cent of catches.

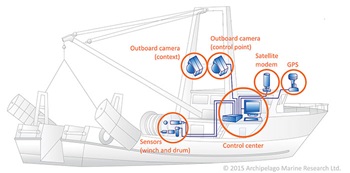

E-monitoring involves a set of cameras and sensors installed on vessels to monitor and record fishing activities. Three or more high-definition cameras cover all activity areas on fishing vessels. There is also a hydraulic gear sensor, a drum sensor, a GPS receiver, satellite communications and a control centre. The sensors trigger the video recording, which is stored in a hard drive in the control centre, and transmits live data on location to AFMA for real-time monitoring.

The new AFMA program is the result of five years of development, in conjunction with the commercial fishing sector. This has included extensive trials to determine whether the technology could be used to verify information fishers provided in their logbooks.

Based on the trial results, and in consultation with commercial fishers, in July 2015 AFMA made e-monitoring a mandatory part of its compliance program for the 75 vessels fishing in the Commonwealth’s Eastern Tuna and Billfish Fishery, the Western Tuna and Billfish Fishery and the Gillnet, Hook and Trap Fishery.

In other Commonwealth fisheries, human observers continue to provide the basis for logbook validation.

AFMA CEO James Findlay says e-monitoring has been a game changer for cost-effective fisheries management and industry assurance. “The more exposure we and industry have to this technology, the more we have come to realise just how powerful a tool it can be.”

He says the benefits of e-monitoring include increasing the accuracy of catch reporting and verifying interactions with threatened species – and ensuring that fishers are doing the right thing during these interactions.

The value of that capacity was demonstrated in February 2016, when a vessel unintentionally landed a whale shark in the Small Pelagic Fishery. The vessel’s e-monitoring system was quickly able to provide footage to confirm details such as the time the shark spent out of the water and the procedures the crew used in handling the animal.

Responsive monitoring

One of the major advantages of e-monitoring compared to human observers is the level of coverage it can provide in ‘sensitive’ fishing zones. While 10 per cent of video footage is reviewed as the base level of monitoring – the same as was previously provided by human observers – AFMA reviews 100 per cent of footage for fishing trips in the Australian sea lion and dolphin zones.

AFMA’s electronic manager, Mike Gerner, says this aspect of e-monitoring is a positive one for the commercial fishing sector, allowing fishing to be undertaken in these sensitive zones. “It can support fishing activity that would not have been financially viable using a human observer.”

It also has the potential to provide fishing operators with more flexibility, given that each individual vessel can be monitored and there is more individual accountability.

For the commercial fishers who fund the operational costs of the monitoring, the financial benefits have gone some way to assuage their concerns about the increased level of scrutiny.

Renee Vajtauer, executive officer of the fishing industry’s Commonwealth Fisheries Association (CFA), says industry recognises the lower cost of e-monitoring compared with human observers. “E-monitoring provides a great validation tool for industry members to confirm that logbooks are being filled in correctly and publicly available fisheries information is accurate.”

However, she says there are lingering concerns about the potential for footage to be used “outside of fisheries management”, possibly with the specific aim of undermining fishing operations.

Location, location, location

E-monitoring systems as shown in the diagram (and in photo below) consist of multiple cameras that capture all activity areas on board.

E-monitoring systems as shown in the diagram (and in photo below) consist of multiple cameras that capture all activity areas on board. Catch monitoring by either electronic or human observers is in addition to the mandatory use of vessel monitoring systems (VMS) in Australia’s Commonwealth fisheries.

VMS that transmit location data have provided a base level of vessel monitoring for decades, helping to identify authorised vessels from those fishing illegally in Australian waters.

The VMS used in Commonwealth fisheries monitor a vessel’s position, course and speed using AFMA-approved equipment installed on each vessel. These transmit encrypted location data via satellite to an AFMA receiver.

The introduction of new fishing zones and marine parks has seen a growing interest in expanding VMS in a number of state fisheries, and within areas such as the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park.

This is in part driven by the growing community emphasis on sustainability and providing higher levels of fisher and management accountability.

The UK-based firm SuccorfishM2M is a global leader in VMS technology in a wide range of industries. Company spokesman Tom Rossiter says the technology has a valuable role to play in sustainable fisheries management in Australia and around the world.

“Today more than ever the fishing industry must evidence its activity or face being overlooked by the marine planning process. Spatial information is also critical to biological fisheries management, and increasingly it’s becoming a requirement for market access,” he says.

In addition to vessel location data, Tom Rossiter says VMS can also provide additional information such as catch, fishing effort and environmental monitoring. The data is transmitted over secure, encrypted systems.

New technology is making these systems less expensive, and more attractive for use in fisheries management.

“Traditionally VMS has only been used on larger vessels, and this was driven by relative risk, the size of the technology and cost,” says Tom Rossiter. “Today, there is wider acceptance that fisheries management would benefit from having all fishing vessels monitored,” he says.

The new generation of technology offers VMS devices that are about the same size as a compact digital camera. Some can link to mobile phone networks for transmissions, rather than satellites, which reduces operating costs. In Australia these are generally effective up to 32 kilometres offshore. These systems also cost hundreds of dollars, instead of thousands of dollars.

This is allowing more fisheries to explore the potential of VMS as a management tool. In the Northern Territory, Succorfish M2M is working with the Department of Primary Industry and Fisheries on a monitoring system for the Mud Crab fishery.

“As well as monitoring the location of the vessel, we also want to know with certainty where the pots are located and how regularly they are worked,” Tom Rossiter says. This would provide valuable information for fisheries managers about fishing intensity, yield and catch per unit effort.

“Ultimately as a manager you would like a fully documented fishery, and our technology is moving us closer to this goal all the time,” Tom Rossiter says.

AIS alternative

Photo: AFMA

Photo: AFMA An even simpler and cheaper vessel-tracking option is the use of automatic identification systems (AIS). An AIS transmits a unique vessel identification, position, course, and speed over a VHF radio signal, which can be picked up by nearby ships, AIS base stations, and an increasing number of specially equipped satellites.

These are an essential safety system required by the International Maritime Organisation for:

- vessels of 300 gross tonnage and upwards engaged on international voyages;

- cargo ships of 500 gross tonnage and upwards not engaged on international voyages; and

- passenger ships, irrespective of size, which carry more than 12 passengers.

In Australia, AISs are regulated by the Australian Marine Safety Authority (AMSA). AISs are not compulsory for many fishing vessels and skippers can turn off systems if they feel their operation is jeopardising the safety of their vessel or crew.

Because the AIS broadcasts are transmitted by VHF radio they can be monitored by anyone with VHF radio access. It’s a very public system, designed to improve safety at sea by preventing collisions and helping to track vessels in an emergency.

Because AISs are easily installed with cheap off-the-shelf hardware they have been adapted for use in some international fisheries to monitor vessels. However its primary purpose is as a maritime safety tool, and it has limitations in terms of fisheries management.

There has also been limited support in the Australian fisheries sector for the use of AIS because of the public nature of the location transmissions. Fishers, traditionally protective of their fishing locations, are also wary of being targeted by anti-fishing lobby groups.

FRDC Research Code: 2009-076

More information

Mike Gerner, 02 6225 5379,