Sustainable growth in aquaculture across Australia’s north could help local industry meet increasing global demand for high-quality protein

There is scope to expand northern Australia’s farmed prawn industry – which embodies world best practice environmentally while producing record yields – and other aquaculture ventures. Photo: Nick Moore

There is scope to expand northern Australia’s farmed prawn industry – which embodies world best practice environmentally while producing record yields – and other aquaculture ventures. Photo: Nick Moore By Melissa Marino

Increasing aquaculture production across northern Australia (Figure 1) would benefit local industry and help meet global food needs as demand for safe, high-quality protein grows, researchers and producers say.

Significant expansion has been identified across Australia’s north, the area north of the Tropic of Capricorn, where the value of aquaculture production is estimated at about $200 million. Aquaculture species in this region included oysters, prawns, Barramundi (Lates calcarifer), pearls and freshwater fish.

The Australian Government, as part of its vision for redeveloping northern Australia, says aquaculture could conceivably be increased to an industry generating two or three times the current figure by the end of this decade.

“Quality Australian seafood can play an increasing role in helping feed our Asian neighbours,” the paper says. “Suitable sites for a large sustainable aquaculture industry exist across northern Australia and businesses are pursuing large-scale opportunities.”

The potential for growth is backed by CSIRO research that has identified half a million hectares in each of Western Australia, the Northern Territory and Queensland as suitable for pond-based saltwater aquaculture. These areas are at a safe distance from mangroves or other sensitive areas.

CSIRO Food Futures Flagship acting director Nigel Preston says sustainable aquaculture development will be important in meeting not only local food requirements but also burgeoning demand for high-quality seafood from Asia’s growing middle class.

“Our neighbours are absolutely prepared to pay a premium for food they know is safe and sustainable – for the provenance of where it has been grown,” he says.

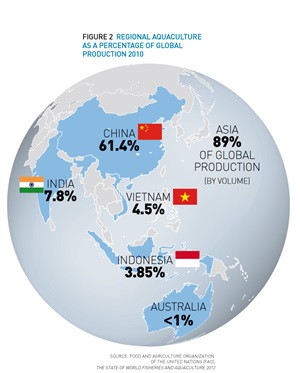

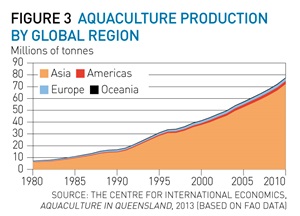

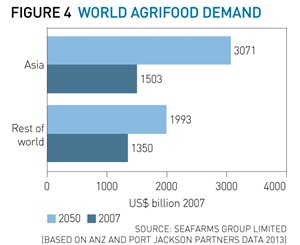

Currently, Australia’s contribution to the global seafood market is small. Australia imports about 72 per cent of the seafood it consumes and in 2010 the contribution of the Oceania region, including Australia, to global aquaculture production was only 0.3 per cent (Figure 2). Asia accounts for nearly 90 per cent of global production (Figure 3). Meanwhile, food demand in Asia is expected to double by 2050 (Figure 4).

Nigel Preston says a growing global demand for seafood is reflected in trade figures that show China was a net exporter of farmed prawns and other seafood up to four years ago. Today it is a net importer, he says, which demonstrates its increasing appetite for seafood.

“There is a global challenge to provide healthy protein to feed more and more people and Australia needs to take a serious look at the expansion of sustainable saltwater aquaculture to take advantage of this opportunity,” he says.

Quality and quantity

Nigel Preston says the Australian aquaculture industry adheres to the highest environmental standards in the world, which is one reason its produce is highly desirable. For example, the environmental management of prawn farming is world’s best practice, as determined through a seven-year, multi-agency study by CSIRO, the FRDC and others into large prawn farms in Queensland and New South Wales.

Among the study’s findings were that advances in treatment systems and practices had enabled some farms to increase production with no net increase in sediment or nutrient loads discharged into receiving waters.

It found the industry had achieved an effective balance between economic gains and conserving ecosystems. And with operating practices and regulations in place, the study found that there was significant opportunity for expansion without compromising the economic and environmental sustainability of the industry.

“The industry has the strictest environmental practices and policies in place, so the licence to operate is based on the science that determines there is no adverse impact on receiving waters,” he says.

Nigel Preston says cooperation between industry and researchers has seen Australian farmed prawn enterprises innovate to embody world best practice environmentally, while also producing record yields.

In 2010, through a 10-year selective breeding program, CSIRO’s Food Futures Flagship and prawn farmers developed an Australian Black Tiger Prawn (Penaeus monodon) labelled the ‘perfect prawn’. Delivering improved growth and survival rates resulting in record yields, it is also a sustainable and renewable resource grown in drought-proof saltwater ponds. This prawn has also won multiple awards for flavour.

Last year, to further the case for sustainability, CSIRO researchers produced a feed for farmed prawns, NovacqTM, which contains no wild-harvest fishmeal or oil. This, Nigel Preston says, is a game changer for prawn farming, potentially meaning it will no longer be reliant on wild-caught fishery products for feed, which is a legitimate concern regarding the industry.

“In Australia we’ve got some of the best elite prawn genetics, we’ve got a totally sustainable feed, we’ve got the strictest environmental management practices in the world and we’ve got a fantastic opportunity to produce high-quality, high-value protein at a scale that would allow Australia to not only become more self sufficient in seafood but to also respond to the huge demand for high-quality proteins from Asia,” he says.

Nigel Preston says aquaculture delivers a high-quality, cost-effective, sustainable protein. In 2013, the global production of seafood surpassed beef and demand is expected to continue to increase as the world’s population grows.

“If you want to ramp up the production of high-quality protein, the most efficient method in terms of tonnes per hectare is production of fish or prawns in saltwater ponds or cages,” he says. “So we need to ensure that the new generation of Australian aquaculturalists have the means to operate sustainably and with certainty.”

Model for expansion

Global nutrition needs will be met not only through continued advances in the beef, dairy and grain sectors, but also through new opportunities for innovation and expansion in aquaculture, Nigel Preston says. And such an opportunity is being harnessed by the team behind Project Sea Dragon, he says.

Project Sea Dragon is an ambitious plan for pond-based prawn aquaculture development across northern Australia that seeks to increase national prawn production dramatically over the next seven to eight years.

Farmed prawn production in Australia covers less than 1000 hectares, but Project Sea Dragon, a Seafarms Group Limited project, plans to increase that by at least 10 times by developing 10,000 hectares of land into ponds to produce 100,000 tonnes of Black Tiger Prawns a year.

In a departure from the industry standard, which is characterised by small farms supplying to the domestic market, Project Sea Dragon involves large-scale production with an eye to supplying the growing export market – a kind of ‘big agri’ for prawns.

“In other words, we are talking about what Australian agriculture has done for a long time with grain and livestock exports,” says Commodities Group economist Daniel Fels. “We’ve got a preference for large farms because, as Australians have known from very early days, they give you economies of scale.”

Daniel Fels says the plan is ambitious but realistic in a climate where demand is strong and growing, and land is available.

Of the seven million tonnes of prawns eaten throughout the world every year, four million tonnes are farmed, he says. Twelve years ago, less than 1.5 million tonnes of prawns were farmed.

“There’s been a massive ramp-up of supply but there has also been a massive ramp-up of demand and it appears to be a good, strong, sustainable demand,” he says.

But through this period of growth in supply and demand, Australia’s farmed prawn production has remained at about 4000 tonnes a year. “Australia hasn’t joined that prawn boom, so while our project is ahead of the curve in the Australian context, in the global context we are possibly late adopters,” he says. “We are catching up.”

Daniel Fels says there is promising potential across Australia’s north to develop the land required, particularly in WA and NT, where government agencies are helping guide investors through the regulatory processes involved in establishing an aquaculture venture.

In NT, the cause has been furthered by the identification of aquaculture in recent legislation as a possible non-pastoral use of pastoral land. In WA, increased opportunities could also emerge for sea cage expansion after the government recently opened a larger aquaculture area in the state’s north.

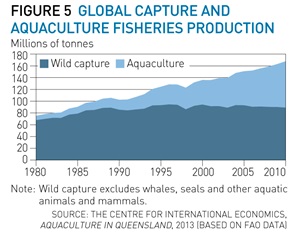

“In the north of Australia, there is land and there is water and there are under-utilised reserves of both,” Daniel Fels says. “We looked at what we could do with land and water and an extremely efficient use of both is aquaculture – and when we see what has happened to aquaculture in the rest of the world (Figure 5) it starts to really resonate.”

Case-by-case

Nigel Preston explains aquaculture development is still largely a state issue and therefore development of the industry has been variable across the country.

In Tasmania and South Australia, relatively clear policy and zoning is in place for the sustainable development of aquaculture, but in other states industry has faced challenges involving complex legislation and an array of agencies to work through.

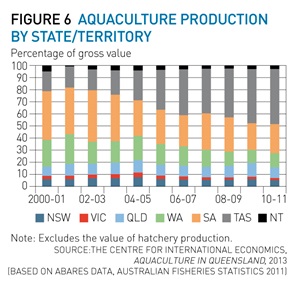

The success of Tasmania and SA’s aquaculture zones for the high-value species salmon and tuna, respectively, is reflected by 2010–11 figures published by the Centre for International Economics (CIE). It shows Tasmania produced about 46 per cent of Australia’s total aquaculture production followed by SA at about 24 per cent (Figure 6).

Marine Farming Development Plans in Tasmania cover more than 10,000 leasable hectares and over the past decade growth in the Tasmanian aquaculture industry has averaged about 14 per cent – the highest of all Australian states and territories, according to the CIE report. Queensland has the second-highest growth rate (at four per cent), despite a regulatory framework that is relatively complex, involving multiple agencies across all three levels of government – local, state and Commonwealth, the report says.

Australian Prawn Farmers Association executive officer Helen Jenkins cites the complex system compounded by environmental regulations regarding the Great Barrier Reef as a deterrent to development in Queensland. No new prawn farms have been approved in the state for more than a decade.

A Queensland Competition Authority (QCA) review is investigating options for reforming regulation of the state’s aquaculture industry. Helen Jenkins has welcomed the review, saying she believes there is potential to expand prawn production from its current area of 692 hectares in Queensland to 5000 hectares without negative environmental impact.

“This industry sector has campaigned long and hard for a regulatory approach that facilitates expansion … while balancing environmental protection,” she says.

The Project Sea Dragon team has also put a submission to the QCA review and Daniel Fels says he is optimistic about prospects in Queensland.

The process for development in northern Australia is complex, but the company has been working carefully with state and federal governments, land owners and other stakeholders through a ‘matrix’ of issues involving Native Title, and the geophysical, employment, logistics and environmental sustainability, he says.

Meanwhile the Australian Government is producing a white paper on the development of northern Australia. Its terms of reference do not explicitly include aquaculture, but the secretary to the Minister for Agriculture, Senator Richard Colbeck, has aquaculture on his agenda. “Our policy is to create a national aquaculture strategy,” he says.

The National Seafood Industry Alliance has made a submission to the process.

Chris Calogeras, chief executive officer of the Australian Barramundi Farmers Association, assisted the alliance with its submission and says aquaculture is implicit in agricultural development.

In its submission, the alliance says northern Australia has great potential for further aquaculture development but convoluted legislation emanating from overlapping agencies and state legislation lacking defined pathways for sustainable growth have been major obstacles.

Chris Calogeras says a national development strategy for aquaculture would benefit industry. “If we could get a national agreement around priorities or a policy it would make it easier, but each state has its own issues to deal with,” he says.

There is the potential for expansion of farmed Barramundi, but crucial to growth is that a solid underlying policy and legislative framework is established first, he says.

This would relate not only to environmental issues but also to workable regulatory regimes involving logistics, workforce agreements and training. In addition, marketing strategies need to be developed to ensure that additional production can be absorbed into and grow the market.

Indigenous Australians must also be part of the conversation about expanding aquaculture in northern Australia where developments take in their land and waters, says Chris Calogeras, who also provides support to the FRDC’s Indigenous Reference Group.

“Our focus on an industry level is to get the existing structure right so that people can operate effectively and efficiently, and that will drive development,” he says. “There’s massive potential but if we head off without getting the bones of it right, it could be fraught.”

Applications open for primary production study scholarships

FRDC-sponsored Nuffield scholar Wayne Dredge

FRDC-sponsored Nuffield scholar Wayne Dredge The FRDC will again sponsor the Nuffield Australia Scholarship program, with applications closing for the 2015 scholarships on Monday 30 June 2014.

Nuffield Australia chair Andrew Johnson says a total of 25 scholarships are on offer, sponsored by a range of leading primary industry and business organisations.

Commercial fisher Wayne Dredge, from Lakes Entrance in Victoria, was awarded a 2014 Nuffield Scholarship, jointly sponsored by the FRDC and Woolworths. His study program will research methods of hook-based fishing compared to gill-net fishing for Gummy Shark (Mustelus antarcticus), taking into account environmental impacts of the different fishing techniques, with visits to Canada, New Zealand and Norway.

As owner and operator of the vessel Opal Star, Wayne Dredge spends up to eight months a year at sea, with an average annual harvest of 15 tonnes of Southern Rocklobster (Jasus edwardsii) and 25 tonnes of primarily Gummy Shark. Other catch includes octopus, some scale-fish and crabs.

Nuffield Scholarships provide a six-week global focus program for primary producers and managers, looking at the latest developments and trends in agriculture. It also includes up to 10 weeks of individual study that allows scholars to pursue a particular area of interest.

Writing from on the road, Wayne Dredge says the scholarship has taken him from shanty towns in South Africa, to a school run by a former Kenyan Army Major General and national hero.

He has visited one of the last great cattle ranches of east Africa and dined with a Russian oligarch who was agriculture minister during the Chechen War in 1999. He has travelled through the old Eastern Bloc of Europe to the last of the major European manufacturing powerhouses in Germany, to the corridors of power in Washington, DC, and to the very centre of US agriculture, in Nebraska.

“Having finished the global focus program, I’m now studying the seafood markets of the city that never sleeps. What does this have to do with commercial fishing in Australia? The answer is everything. Lessons learned from other production sectors are invaluable and it is this that Nuffield offers better than anyone.”

More information

Jim Geltch, 03 5480 0755, 0412 696 076

jimgeltch@nuffield.com.au

FRDC Research Codes: 2002-042, 2013-413

More information

Nigel Preston, 07 3833 5957

nigel.preston@csiro.au