Fishers are often at the frontline in close encounters with the weird and wonderful creatures that make up our marine and freshwater environments

Australian National Fish Collection director Daniel Gledhill with specimens awaiting formal identification and registration in the collection: just some of the treasure-trove awaiting further study.

Australian National Fish Collection director Daniel Gledhill with specimens awaiting formal identification and registration in the collection: just some of the treasure-trove awaiting further study. Photo: Carlie Devine, CSIRO

By Gio Braidotti and Catherine Norwood

Occasionally something strange and unusual lands on the deck of a fishing trawler, highlighting the uniqueness of marine biodiversity in Australian waters, where new species continue to be discovered at the rate of about one a week.

In January 2015, a New South Wales fisher hauled in a specimen of the rarely seen and endearingly monstrous Goblin Shark (Mitsukurina owstoni). In the same month in Victoria, a trawler landed a prehistoric-looking Frill Shark (Chlamydoselachus anguineus). Both events generated significant international attention.

Fisher Lochlainn Kelly, 22, who pulled up the Goblin Shark off Green Cape on the NSW southern coast, told the Sydney Morning Herald he was excited by the find, which he had previously only seen in photographs. That excitement has resonated with the public: a YouTube clip of the Australian Museum’s fish collection manager, Mark McGrouther, processing the specimen has garnered more than one million views.

The Goblin Shark, billed as an “alien of the deep”, normally lives at depths of 300 to 900 metres. In these dark waters it targets prey through electroreceptors on its long snout that sense electrical energy from other marine wildlife.

The Victorian catch of a Frill Shark also generated “phenomenal international interest”, according to the CEO of the South East Trawl Fishing Industry Association (SETFIA), Simon Boag.

He published a quickly compiled ‘odd spot’ piece in SETFIA’s e-newsletter about the catch by David Guillot, skipper of the trawler Western Alliance.

Within a few days he had received 500 emails from media around the world wanting more information about the “prehistoric monster”. Supposedly linked to legends of sea serpents, the Frill Shark featured as a global news item in the following weeks.

The Frill Shark was caught in water 700 metres deep near Lakes Entrance in Gippsland, although it usually lives at depths of more than 1200 metres.

With the face of an eel, the body of shark and a mouth full of 300 needle-like teeth in more than 25 rows designed to snag soft-bodied prey (including squid and octopus), it had little trouble gathering attention.

While both of these rarely encountered species had previously been identified, about 50 new species are discovered in Australia’s marine and freshwater ecosystems every year – and that is just the fish.

Archival illustration of a Frill Shark, circa 1930.

Archival illustration of a Frill Shark, circa 1930.Dedicated discovery

The painstaking work of searching for and detailing the distinguishing features of a new species and its habitat is led largely by researchers, but is supported by fishers across all sectors. Fishers provide catch samples and also host scientific observers on their fishing vessels, both of which supplement dedicated scientific sampling expeditions.

CSIRO hosts the Australian National Fish Collection and director Daniel Gledhill says it has taken many decades to build a collection that reflects an accurate picture of Australia’s marine life – and the collection is still growing.

“Knowledge improves in incremental steps – there are steps forward and backward stumbles when specimens turn up that force a rethink of existing groupings. And for Australia’s marine organisms, that is still happening.”

Juvenile Black Dragonfish

Juvenile Black Dragonfish Photo: Derrick Cruz

Part of the reason for this is the sheer complexity of the marine environments involved. Australia manages the world’s third largest exclusive economic zone and it ranges from tropical northern waters to a temperate south and on to chilly sub-Antarctic waters, reaching depths of 5000 metres.

Some of these regions have provided niche habitats for evolution to follow its own unique trajectory. Fish may share one gigantic global pool of water, but many do not opt to swim particularly far. Rather, they appear to have congregated in ways that have allowed them to adapt and specialise.

“In the tropics there is a lot of biodiversity that is shared with neighbouring Asia–Pacific nations but in the south we have some of the highest rates of endemism in the world – that is, species found only in Australian waters and nowhere else in the world.”

While both the Goblin Shark and Frill Shark are found in international waters, Australia’s abundance of isolated ecological niches has nurtured about 5000 known fish species, nearly 30 per cent of which are found only in Australia.

“But that’s just fish, and we know these pretty well compared with many invertebrate groups, such as sponges,” Daniel Gledhill says. “It’s important we understand the spectrum of this biodiversity and the way it all interacts to ensure the sustainable and responsible management of our unique aquatic resources, heritage and industries.”

Larval hotspot

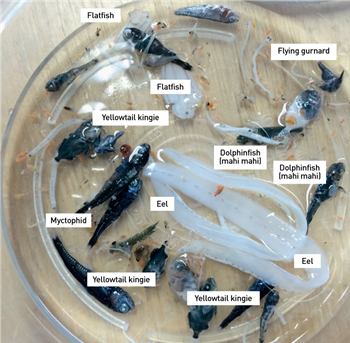

Larval fish collected from an ocean eddy by researchers on RV Investigator.

Larval fish collected from an ocean eddy by researchers on RV Investigator.Photo: Iain Suthers

Australia’s newest research vessel, RV Investigator, is helping researchers to identify more marine species and to document the dispersal patterns of known species.

In June this year researchers onboard RV Investigator studied the species caught in an ocean eddy off the coast of Sydney. They discovered it was a hotspot for rock lobster larvae at a time of the year when they were not expecting to find larvae.

The chief scientist for the voyage was University of NSW marine biologist Iain Suthers, who was astounded to find juvenile commercial fish species such as bream and Tailor 150 kilometres offshore.

Researchers had thought that once larvae were swept out to sea that was the end of them. However, the ocean eddies have now been identified as nursery grounds along the east coast of Australia.

The team of researchers also discovered a cluster of extinct volcanoes likely to be 50 million years old, which are about 250 kilometres off the coast of Sydney in 4900 metres of water.

The four extinct volcanoes in the cluster are calderas – a volcanic crater that forms after a volcano erupts and the land around it collapses.

The largest caldera is 1.5 kilometres across the rim and rises 700 metres from the sea floor.

Sampling Australia’s abyss

Another RV Investigator voyage is currently underway.

Tim O’Hara from Museum Victoria is leading a 32-day voyage onboard RV Investigator to sample marine life along the base of Australia’s eastern continental margin. The voyage departed from Brisbane in November 2015.

The project aims to discover the fauna of Australia’s abyssal sea floor, down to 4000 metres below the sea’s surface.

Never before has an Australian expedition focused on the biodiversity of our vast abyssal environment.

An international team of researchers will survey from Fraser Island, Queensland, to Tasmania to investigate the changes in species and genetic composition that occur with latitude and depth. The researchers expect to collect images and measurements of many species for the first time.

Crayfish quest

Eastern swamp crayfish (Gramastacus lacus) from the Lake Macquarie catchment.

Eastern swamp crayfish (Gramastacus lacus) from the Lake Macquarie catchment. Photo: Rob McCormack

Rob McCormack is a man on a mission: to identify and map the habitat of all Australian freshwater crayfish species. He leads a group of up to 25 volunteers, all committed to the Australian Crayfish Project, which has identified almost a dozen new species since it began in 2005.

Four species have been officially confirmed and another six to eight are in the final phases of description and identification. Among the new species is one of the world’s smallest crayfish, the eastern swamp crayfish (Gramastacus lacus). Rob McCormack says it is possible it could have been mistaken in the past as a juvenile of a larger species, but about five centimetres is its fully grown adult size.

“We really have no idea about the different crayfish species, and the extent of these species because in more than 200 years we haven’t really gone looking,” he says. “If no one knows these species are there, and they don’t even have a name, how can we protect them and their habitat for the future?”

The eastern swamp crayfish, for example, is found in coastal New South Wales, where there is extensive urban development on reclaimed swamplands and large areas of its habitat have already been lost.

Although not a trained taxonomist (he is an engineer by training), Rob McCormack has built his expertise as an enthusiastic amateur through field experience and by working closely with fisheries collection staff at various state and national museums.

There has been little direct funding for the project, which is generally carried out during weekend forays into swamplands. “But support and interest from local communities, councils, catchment management agencies, and forestry and national park authorities has been outstanding,” he says.

Many Australian crayfish species are already identified as endangered as a result of habitat loss and invasive species. They are also considered keystone species, helping to preserve the wellbeing of other species in their ecosystems, from fish and turtles, to snakes, mammals and birds.

More information

Rob McCormack, acp@aabio.com.au

Something strange to identify

Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus).

Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus).Photo: www.setfia.org.au

Fishers are often at the frontline of the discovery process, playing an important role to help understand marine biodiversity. For those who have a close encounter with a never-before or rarely seen creature, it is recommended photographs be taken of the whole animal, including close-up shots of markings and individual features, such a fins. If possible, the animal should be preserved frozen in a plastic bag.

Some rare specimens will be of interest to researchers, such as a 7.2-metre, 2.6-tonne Basking Shark (Cetorhinus maximus) that was landed by a trawler fishing in deep water off the Victorian coast near Portland in June.The shark was donated to Museum Victoria.

CEO of the South East Trawl Fishing Industry Association Simon Boag says the association has since established an SMS service that allows its members to alert the research community of any rare catches that might be of interest as soon as possible.

Fishers can also contact their nearest state museum or CSIRO’s Australian National Fish Collection. It may take years of meticulous analysis, but the possibility exists that the specimen could be a new species.

CSIRO’s national collection serves as a reference that is used to classify new specimens by a process of comparisons. It holds 151,000 registered specimens, with many more in freezers, preservative and tissue banks awaiting examination and registration.

The Photographic Index of Australian Fishes, managed by CSIRO, is also used for identification. It contains 40,000 colour transparencies and digital images of more than 2500 fish species, and is the largest taxonomic photographic collection in the Southern Hemisphere.

These images can be accessed through the collection’s website, Fishes of Australia, which is spearheaded and hosted by Museum Victoria and funded by the Australian Biological Resources Study. It is supported by a group of specialists from state museums and CSIRO called OzFishNet.

The original Australian Seafood Handbook, funded by the FRDC, and the free online tool FishMap also provide a searchable atlas of more than 4500 marine fishes catalogued according to their geographical and depth distribution (see FISH, June 2013 issue, "Find your fish online"). It encompasses all of Australia’s commercial seafood species and contains the only photographs in existence of many bycatch species. It also contains images of species from rivers and estuaries and from near-shore. Its coverage spans the tropics to the sub-Antarctic.

FRDC Research Code: 1994-136

More information

Daniel Gledhill, daniel.gledhill@csiro.au