Innovation has been crucial in developing a viable fishery and market for Australian octopus

By Rose Yeoman

Fifteen years ago, when brothers Craig and Ross Cammilleri were working in the West Coast Rock Lobster industry, they saw high numbers of Gloomy Octopus (Octopus tetricus) captured as bycatch – usually destined to become bait. They wondered if the octopus could, with the right development and marketing, become a profitable product.

The Cammilleris have come a long way since 2001 when they decided to act on their idea, working with the Department of Fisheries, Western Australia, to officially initiate “developing a new fishery” for octopus.

After 15 years of work the fishery is nearing final, formal recognition as a “managed fishery”, and has Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) pre-accreditation.

The Cammilleris have also taken a step beyond domestic demand, breaking into US markets with their branded Fremantle Octopus range of delicacies.

When they formed Fremantle Octopus they initially bought live octopus from other fishers with the intention of growing them out in an aquaculture setting or by ranching them. However, the supply and size were too variable and this approach proved unviable.

The general manager at Fremantle Octopus, Arno Verboon, says octopus fishing at the time was “a cottage industry”. Octopus were harvested from shelter pots, which were essentially pipes with an open end. Yields were relatively low and harvesting was cumbersome and labour-intensive.

Trap innovation

These issues led Craig Cammilleri to consider how to build a better trap. In 2006, making use of his knowledge of octopus behaviour, he began developing a new design that would capture octopus without causing any damage to the animal.

Octopus typically respond to encounters with crabs by winding their tentacles around the crab to crush the claws and prevent themselves being nipped. With this in mind, Craig Cammilleri created an artificial lure in the form of a plastic orange crab as the bait for his new trap.

Rather than a traditional pot or pipe, the new trap is a rectangular plastic box. The crab is fitted with a light-emitting diode that flashes every six seconds to attract the octopus. In order to crush the crab, the octopus must climb into the box and this triggers the closing mechanism on the trap.

The so-called ‘trigger trap’ has been through several design stages and has impressive environmental credentials. It can only catch one octopus, and only an octopus strong enough to trigger the trap, which also protects it from predation until it is harvested. And if a trap is lost at sea only one octopus is lost: the traps do not contribute to ghost fishing.

At the Department of Fisheries, WA, manager for the northern bioregions Shane O’Donoghue says Craig Cammilleri’s trap has revolutionised the industry and it has been crucial to the development of the fishery.

The traps are produced by a separate Cammilleri company, Octopus Technologies Pty Ltd, and were approved for use in 2006. The most common configuration is a cradle of three traps together, which has proven up to 15 times more efficient than shelter pots.

By 2012, 95 per cent of all octopus fishing effort on the west coast was using trigger traps. Now about 20,000 trigger trap cradles are arrayed around the WA coastline and Ross Cammilleri predicts the harvest in the expanding fishery will be 180 tonnes in 2015-16.

At present trigger traps are unique to the WA Octopus Fishery. Tasmania, the only other Australian state with an octopus fishery, uses shelter pots.

Fishery status

When the Cammilleris began working with WA Fisheries to develop what they saw as “an underutilised resource” the first step was to initiate the Developing New Fisheries process (outlined in Fisheries Management Paper No. 130). This recognises a fishery that has unexploited potential. The second stage was to obtain a declaration for an Interim Managed Fishery.

The Developing Octopus Fishery was set up in 2001 and in 2015 was reclassified as ‘interim managed’ under the Octopus Fishery Interim Management Plan (Figure 1), which limits type and amount of gear used by commercial operators.

At present the WA’s octopus fishery occupies three zones and two bioregions. The Department of Fisheries, WA, sets maximum trap numbers for each zone and individual fishers have been allocated a set number of units within the management plan, which corresponds with the number of traps they are permitted to use in each zone. The units are fully transferable and may be sold, purchased or leased.

The fishery has passed pre-assessment by the MSC and licensees are in discussion with the Department of Fisheries, WA regarding moving to full MSC assessment.

The final stage for the fishery, if certain criteria are met, will be the declaration of managed fishery, where long-term access is granted to fishers through legislation or by a management plan.

The FRDC has supported research for the development and management during the past few years to evaluate the potential capacity of the new fishery. Shane O’Donoghue says that although less than 200 tonnes of Gloomy Octopus are landed each year, a new report to be released in 2016 describes the potential as 1000 to 2000 tonnes.

“The capacity of the new fishery under the new management plan is based on 630 tonnes for the fishery and there is the capacity for further expansion over time based on continuous positive research results,” he explains.

When Fremantle Octopus was first established, the Cammilleris recognised that they could not develop the fishery by themselves.

“So we invited our fishers to participate in ownership. If they stayed with us for five years, they would be invited to participate in ownership of the octopus fishery licence when the fishery became managed. And we’re doing that right now,” he says.

Figure 1: Developing Octopus Fishery Interim Management Plan.

Figure 1: Developing Octopus Fishery Interim Management Plan. The Cammilleris no longer engage in fishing themselves and purchase octopus from 10 fishers who work the licence allocation off the WA coast between Leeman and Cape Leeuwin. They supply exclusively to Fremantle Octopus.

Apart from Fremantle Octopus and Octopus Technologies, there is a third business: Occoculture, which is exploring the potential to farm the species. With the aid of scientist Sagiv Kolkovski from the Department of Fisheries, WA, a model octopus farm was established in an attempt to close the life cycle gap and grow all octopus life cycle stages in an aquaculture setting. Although this has not yet been achieved, a great deal has been learnt about octopus diet and aquaculture techniques applied to the Gloomy Octopus.

Products and markets

Fremantle Octopus has its head office and factory facility near Fremantle, WA. Octopus are processed on site within 24 hours of being caught and packaged either flat (as “hands”), where body and tentacles are placed into a flat, flexible plastic package, or they are steamed, cut into pieces, marinated in herb-flavoured oil and packaged into jars.

About 80 per cent of products are sold in Australia and 20 per cent are exported to Singapore, Hong Kong, Dubai and cities in the US.

During a recent visit to the US, Arno Verboon attended the Food and Wine Festival in Atlanta.

He says many chefs commented that the flavour and texture of their product was superior to the locally available Spanish octopus. At the recent Gourmet Escape food and wine festival in Margaret River, WA, English celebrity chef and restaurateur Rick Stein also described Fremantle Octopus product as the “best in the world”.

Seven-step process

(Illustrated in the 7 photos above)

1 Freshly harvested octopus is steamed. 2 Trays are unloaded from the steamer. 3 Quality is evaluated after cooking. 4 Immersion in an ice bath completely stops the cooking process. 5 The octopus is cut into smaller pieces and seasoned. 6 Seasoned octopus is packed into jars and marinated in oil. 7 Final quality check before packing and distribution.

International octopus aid

It is not just Australian octopus fishing that will benefit from trigger trap technology. For several years, Ross Cammilleri has pursued the idea that the trigger trap could be used to enhance the economy, diet and food security in developing countries.

And now, with the aid of a $57,000 grant from the Australian and Mauritian governments, Octopus Technologies will develop a pilot project for establishing a sustainable octopus fishery on Rodrigues, Mauritius, and exporting product to the European Union.

“The traditional fishing method involves spearing the octopus with a long metal pole, but the technique is damaging to coral and the ecology of the reef,” Ross Cammilleri says.

“Replacing the metal poles with trigger pots and training locals in the harvest, grow out and processing of their octopus species – Octopus cyanea – will enhance sustainability.”

He explains that in Rodrigues, fisheries were historically characterised by an ‘open-access’ approach due to lack of employment opportunities in other sectors.

In 2011 a study supported by the Indian Ocean Commission predicted that the local O. cyanea stock would be depleted by 2015 if nothing was done to reverse the trend of overfishing.

The problem was compounded by a steady rise in the number of fishers and the low genetic diversity of Rodrigues’s octopus stock. In the event of fisheries collapse, it would be difficult for the octopus to recover.

To address these concerns, the SmartFish food security program of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations prepared for the first ‘Octopus Closed Season’ in 2012.

Rodrigues has an “allowances” system where registered fishers are compensated for days that they are unable to fish due to poor weather or if a fishery is temporarily closed.

However, during the two-month Octopus Closed Season of 2012 the Rodrigues authorities opted for an environmental services policy rather than a compensation policy as paying fishers a daily allowance would have heavily affected the regional budget as well as creating dependency.

Fishers were employed on the island in diverse jobs including revegetation projects, maintenance of riverbeds and reservoirs, invasive plant species control, beach clean-ups or surveillance of fish stock.

The closure in 2012 and subsequent years has successfully rejuvenated the fishery, which is now ready for a boost from trigger trap technology.

Photos

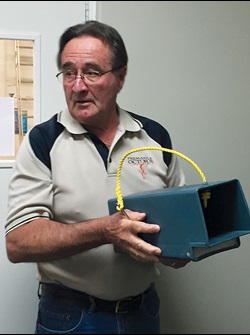

Ross Cammilleri holds the Fremantle Octopus ‘hands’ (Top), raw tentacles, tenderised and vacuum packed as a premium product and popular with restaurants and commercial kitchens.

The new octopus trap (Bottom), developed by Craig Cammilleri, is many times more efficient than the traditional clay pot (Middle) used to catch octopus.

Choose your dish

Octopus have a mild flavour and dense texture, making them ideal for marinating, blanching and chargrilling.They are best cooked quickly over high heat or simmered slowly for 15 to 20 minutes in a flavoured broth.

Marinating helps to tenderise the flesh and strengthen flavour for enhanced results when fast cooking such as in a stir-fry or on a barbecue.

Blissful bites – Fremantle octopus skewers in pizza oven. Photo: Fremantle Octopus

Blissful bites – Fremantle octopus skewers in pizza oven. Photo: Fremantle Octopus Mediterranean and Asian flavours work well with octopus, including fresh basil, mint, coriander, chilli, lemon rind, Spanish onion and capsicum with grilled or barbecued octopus, served with a balsamic or rice vinegar dressing. Marinated, blanched or chargrilled octopus is a tasty addition to warm salads or antipasto platters.

About 90 per cent of an octopus is edible. With whole octopus, the guts, hard beak and ink sac are removed and although the head is edible, it can be tough and chewy.

Blissful Bites

Fremantle Octopus skewers in pizza oven

- 50 grams steamed octopus per skewer

Prep and cook

- Cut up steamed hands, skewer and marinate.

- Cook in pizza oven for five minutes or until brown.

FRDC Research Code: 2010-200

More information

Ross Cammilleri, 08 9314 1615,

Arno Verboon, 08 9335 6300,