A tour of the South Australian coast examines the potential of a different marketing approach for Australia’s small-scale commercial fishers

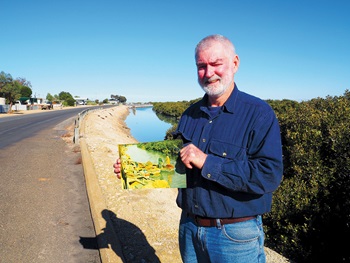

Joshua Stoll with Craig Fletcher, who fishes in the Marine Scalefish Fishery off Wallaroo, SA.

Joshua Stoll with Craig Fletcher, who fishes in the Marine Scalefish Fishery off Wallaroo, SA.Photos: Annabel Boyer

By Annabel Boyer

At a series of meetings with fishers in South Australia to talk about community supported fisheries (CSFs) in the US, Joshua Stoll always starts with his own story.

In 2008, commercial fishers in North Carolina were facing plenty of challenges: low prices for their catch, competition from cheaper imports and public mistrust in relation to the welfare of endangered sea turtles. Add the pressures of ageing boats and gear, competition over waterfront usage and competition with recreational fishers and the commercial fishers were facing a perfect storm.

But the crisis that could have triggered their demise instead proved a crucial opportunity for transformation. Out of it came the Walking Fish initiative, using an approach that has revolutionised the seafood supply chain in its own small North Carolina community.

Walking Fish offered its community the opportunity to ‘subscribe’ to a season of fresh and seasonally caught local fish. This allowed fishers to get a better price for their catch and, crucially, reconnected them with their communities. While the subscription model used by Walking Fish is one approach, the key innovation lies in reducing the distance between fisher and consumer, Joshua Stoll says. A CSF is a fishery connected to and supported by its local community.

Growing movement

Olaf Hansen cooking pipis on his bike barbecue in Goolwa, SA.

Olaf Hansen cooking pipis on his bike barbecue in Goolwa, SA.What’s more, it’s a model that is proving successful in many locations and forms across the US and elsewhere. The CSF network has 75 members connected online via LocalCatch.org.

In 2015, influential author of Four Fish: The Future of the Last Wild Food Paul Greenberg named CSFs as an important trend. Fish 2.0, an engine for business growth in the fisheries sector, has projected that CSFs could generate hundreds of millions of dollars for the US economy.

“People love the idea of fresh local seafood, but for many people it was about putting their money back into a place where they knew it was going into supporting their local community,” Joshua Stoll says.

CSFs have been on the FRDC’s radar for some time. In 2015, the FRDC sponsored Joshua Stoll, founder of Walking Fish and LocalCatch.org, to travel to Australia and speak at Seafood Directions.

Last year, several Australian fishers headed over to the US to learn more (FISH June 2016, "US insights into localised supply chains").

In June 2017, Primary Industries and Regions SA (PIRSA) and the FRDC again sponsored Joshua Stoll to meet fishers here to discuss whether CSFs could provide an answer to some of the challenges SA’s small-scale fisheries face.

Jonathan McPhail, fisheries manager with PIRSA Fisheries and Aquaculture, says that SA’s small inshore commercial fisheries are facing significant challenges exacerbated by the consumer’s lack of awareness about commercial fishing practices.

As Joshua Stoll discusses the challenges faced by fishers in North Carolina, much of what he describes sounds familiar to many of those he meets. Swap sea turtles for Long-nosed Fur Seals, and Flounders and Mullet, and you have the situation faced by fishers in the Lakes and Coorong fishery, which was the first fisheries stop on his tour.

Travelling hundreds of kilometres over several days in June, he also visited Port Lincoln, Port Wakefield and Wallaroo. All the fishers he speaks with can relate to rising operational costs, a lack of trust in commercial fishing and pressures related to access and allocation.

Connecting with communities

Joshua Stoll says that while fishers in North Carolina were initially motivated to participate in the CSF to get a better price for their catch, the benefits have been far greater than a short-term bounce in the bottom line. The CSF model also provides crucial opportunities for fishers to tell their stories and educate their communities about what they do and how they do it.

“People are losing that connection with seafood in their communities and, as a result of that, are losing an understanding of the importance of the commercial fishing sector, both from an economic and a social standpoint,” Joshua Stoll says.

Walking Fish in North Carolina has 400 subscribers who get weekly deliveries of fresh fish. This provides both a local marketplace and a powerful opportunity to educate people. As part

of a subscription, Walking Fish provides customers with information on gear, species and where the fish are caught. It has also partnered with local restaurants to offer recipes for particular species.

Being able to talk to people and send information provides an opportunity to dispel myths about commercial fishing. There is also the opportunity to provide research and personal stories, Joshua Stoll says. This is particularly valuable for small-scale fishers who have an interest in selling the merit of what they do and getting prices for catch that is local, small-scale and uses fishing methods that are low impact.

Market opportunities

Local catch being auctioned at the South Australian Fisherman"s

Local catch being auctioned at the South Australian Fisherman"sCo-operative Limited.

During a visit to the South Australian Fisherman’s Co-operative Limited (SAFCOL), fresh local catch is auctioned off to retailers and wholesalers. Auction prices for the morning’s catch – King George Whiting, Snapper and Garfish – are low compared with retail and restaurant prices for the same fish.

The price gap seems inexplicable when many of the small-scale fishers who catch the fish are struggling to survive financially.

Joshua Stoll says that the combination of low volumes and a diverse array of relatively unknown and undervalued species in SA’s small fisheries provides a situation ripe for the disruption of traditional supply chains.

In a CSF fishers control what the consumer gets, which provides an opportunity to introduce consumers to species they either did not know or may not have considered eating. Walking Fish has asked its customers to rank the species of fish they were given according to how much they liked them and to indicate which species they had never had before. It found that triggerfish (similar to Leatherjackets), a local fish that many people had never had before, was people’s favourite fish. And while many people were resistant to trying a fish such as Mullet, often considered a baitfish, customers ranked it above average on a scale of how much they liked it.

Local perspectives

Nathan Bicknell, executive officer of the Marine Fishers Association, agrees that one of the key advantages of the CSF model is to introduce people to types of fish they might not buy normally or might not have previously tried.

Joining the meeting of the Marine Scalefish Fishery net association in Port Wakefield, he announced that Wildcatch Fisheries SA received Australian Government funding to trial a SA CSF, which, he said, could be a great opportunity for fishers of the Marine Scalefish Fishery. The project, in its scoping stage, is considering a variety of options. These could include partnering with SAFCOL for storage or integrating with the Port Adelaide redevelopment as a way of making a new seafood offering to the public.

“We are looking at broadening people’s experience, by making an offering of a range of different species, both high and low value,” he says.

Many of the people Joshua Stoll spoke with have already gone some way to implementing local marketing strategies. At Goolwa, there are barbecued pipis, cooked on the back of a bicycle. In summer, it is pedalled up and down and coast – an innovative and fun way to introduce Australians to a product many are still unfamiliar with.

Tracy and Glenn Hill, in developing their brand Coorong Wild Seafood, have created niche products and branding that emphasises their products as local and sustainable. They have even renovated their house to provide a space for people to learn and experience their products. Having visited the US last year to learn about CSFs they are enthusiastic about the concept, yet they remain sceptical that it can work in their own small community.

Although enthusiastic, each group of fishers has its own concerns and questions about the model. How do you manage the innate fluctuations in catch and keep your customers happy? How do you decide who gets what? Where does the capability for all these new activities come from?

New ways of working

Joshua Stoll says that pivotal to the success of the Walking Fish CSF was the cooperation needed to collect and organise information. This includes keeping records of who catches what and the prices it is sold for – vital for a profit-sharing enterprise where profits are distributed at the end of the season. The maintenance of a detailed customer database is also vital; it helps to learn what customers like, vary what they are supplied with and is an invaluable communication tool. Joshua Stoll says that Walking Fish has been able to employ a coordinator part time to take care of much of the administration.

At the outset fishers design an operating agreement to ensure cooperation and clear understanding. At the beginning of each season, fishers go through a planning process, anticipating their catch and the species to be targeted. The offering is then built around that seasonality and catch.

Few fishers are wholly depending on CSFs to sell their catch. They continue to make decisions about what to supply to the CSF and what can go elsewhere, depending on demand. It is also important to note that the community relationship at the heart of the success of CSFs requires commitment and longevity.

Many of the SA fishers were concerned about the disruption to existing supply chains and relationships with processors and retailers. In the US, many CSFs have worked to supply their customers with processed fish – partnering with processors.

In Port Lincoln, Gavin Wise of Myers Seafood has begun structuring his business around the diversity and seasonality of local catch, qualities he views as an advantage. Previously a processor and retailer of mostly mussels, he says that relationships with local fishers are key to the success of the venture.

“We have to look after our fishers,” he says, “because without them there is no product.” The fact is that without fresh local catch and fishers there is no supply chain.

Call for input

Wildcatch Fisheries SA (WFSA) has launched a project to develop South Australia’s own community supported fishery (CSF). The project team wants to hear from people interested in being part of the project, learning more about CSFs or providing input as the project develops. To register your interest, to find out more or to be part of WFSA’s project visit its website or email CSF.

The project will include the development of a smartphone-based app to connect fishers with their customers – be they chefs, restaurants or individuals. It will allow customers to buy local catch and also help the public learn more about fishers, their catches and commercial fishing in SA. The targeted customer base is in the scoping stage and could include restaurants or even large retail chains. The app is expected to be launched in May 2018.

A disappearing way of life

Bob Butson

Bob Butson Port Wakefield lies more than 100 kilometres north of Adelaide at the top of the Yorke Peninsula and St Vincent Gulf. Sixty-three-year-old Bob Butson is a second-generation fisher and he took Joshua Stoll on a tour of his hometown, where he has lived and fished for most of his life.

The photo he holds shows his father unloading a catch at Port Wakefield’s wharf. The channel is full of fishing boats tied several boats abreast. But on the day Joshua Stoll visited the channel was almost empty; a single young fisher was cleaning out his boat after a night out on the water.

Over the past 15 years, the number of active fishers in South Australia’s Marine Scalefish Fishery has shrunk from 300 to about 35. Bob Butson says while he supported his sons’ decisions to become fishers 20 years ago, today he is unsure whether there is a future for the way of life he has known.

“It feels like we are in our death throes,” he says of the future of net fishing in Port Wakefield.

As the president of the Marine Fishers Association Inc. Bob Butson’s son Bart puts communication and visibility at the heart of the problem. These days, boats are taken home rather than left tied up in the channel. Catches are packed and sent elsewhere rather than being sold fresh off the water to the inhabitants of the town. Fishing has become all but invisible to the local community.