An electronic pulse trawler operating overseas would not meet Australia’s fishing regulations.

An electronic pulse trawler operating overseas would not meet Australia’s fishing regulations. Photos: Wayne Dredge

With an in-depth look at fisheries management regimes around the world, Wayne Dredge has come to a clear position on what is needed to encourage innovation and efficiency in Australia’s fisheries

By Annabel Boyer

Wayne Dredge got more than he bargained for when he set out to travel the world on a Nuffield Scholarship in 2014.

From joining global discussions on food security to suffering malaria in Malawi, fishing in an Arab dhow and surveying the mind-boggling scale of cold storage in China, his study tour has expanded his world and changed his life in ways he could not have predicted.

It also changed the course of his intended research. When Wayne Dredge set out on his Nuffield tour in 2014, he sought to answer a specific question borne out of his experience as a fisher. His topic was to compare different hook fishing techniques being used around the world.

Wayne Dredge visited a net-making factory in Belgium while researching alternatives to the gillnets used in Australia.

Wayne Dredge visited a net-making factory in Belgium while researching alternatives to the gillnets used in Australia. The aim was clear and simple: to identify alternatives to gillnets. Closures are applied to gillnet fishing due to interactions between shark gillnet boats and Australian Sea Lions and Common Dolphins. Alternative gear use could result in returned fisher access to available waters, and corresponding increase in catch and incomes.

Based at Lakes Entrance in Victoria, Wayne Dredge has fished in the Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery (SESSF) for the past 10 years. He owns two boats and spends five to six months at sea each year. Over the years, he has worked in squid, prawn, estuary, scallop and longline fisheries at different times, and he has also spent seven years in the Victorian and Tasmanian rock lobster sectors.

With the help of the Nuffield Scholarship, he planned to visit a plethora of fishing nations from countries in South and North America to the UK and Europe.

However, as he embarked on his journey, his perspective changed.

“As I began my research it became apparent that even if I did identify alternative methods it was unlikely they could have been implemented here in Australia without causing conflict with other fishing sectors or between fisheries management jurisdictions,” he says.

Three years on and the report that resulted from his Nuffield research has been published. Titled Innovation and Accountability in Commercial Fisheries: The case for reform of harvest and management practices for Australia’s SESSF and related fisheries, it makes a case for a thorough review and reform of Australia’s management system.

Wayne Dredge says that his journey has shown him that Australia’s fisheries excel on a range of indicators – they are innovative and environmentally conscious. But staying ahead requires continual progress.

“In effect, our regulatory structure here in Australia very much inhibits innovation, rather than encouraging it,” he says. To illustrate, he points to his original research concern: fishing methods. Potentially viable alternatives to gillnets in Australia’s SESSF are at odds with regulatory arrangements and so cannot even be considered.

Another example is the practice of discarding high-value fish due to licence restrictions, a regulatory issue resulting from Australia’s Offshore Constitutional Settlements between the Commonwealth and states. It is a practice he says that both harms fishers and wastes a valuable resource.

Wholesale seafood for sale at the Barcelona seafood market.

Wholesale seafood for sale at the Barcelona seafood market. In the course of his travels Wayne Dredge took an in-depth look into the Integrated Groundfish Fishery (IGF) in British Columbia, Canada, and the case of European Union (EU) fisheries management.

Like the SESSF, these are multi-species fisheries with many stakeholders including external groups concerned about overfishing, waste and bycatch. Like the SESSF, they require sophisticated management solutions, and both places hold lessons for Australia.

“The key to resolving issues in Australia will lie in joining the dots that exist between solutions being used in other countries and making those solutions relevant in an Australian context,” Wayne Dredge says.

Canada’s groundfish

In the mid-1990s, due to overharvesting and high grading, British Columbia’s trawl fishery was completely shut down by Canada’s Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO). It was eventually reopened subject to 100 per cent on-board observer coverage, the burden of which had grave economic effects for many in Canada’s trawl fishing industry.

However, in 2006, the DFO accepted a proposal put forward by the industry to integrate all seven of British Columbia’s fisheries as an integrated groundfish fishery under one management plan, with 100 per cent monitoring (on-board observer or electronic monitoring) and an individual transferable quota system.

Wayne Dredge says none of the IGF fishers he spoke with had wanted electronic monitoring on their vessels, but they now saw it as a positive step.

It makes fishers individually accountable by making their activities 100 per cent transparent. This means they can prove they are doing the right thing and that those doing the wrong thing can be individually penalised by authorities instead of punishing the entire sector for the actions of a few.

The Pike Place Market in Seattle, US, is a popular outlet for local seafood.

The Pike Place Market in Seattle, US, is a popular outlet for local seafood. It also levels the playing field because all fishers can be certain that their counterparts in the fishery are complying with the same regulations.

Transferability of quota in a mixed-species fishery means fishers can eliminate discards and waste within the fishery by transferring the necessary quota for non-target species between vessels.

Currently, 300 Canadian vessels participate in the IGF under a single management plan with strict and fully accountable output controls in place for more than 70 species, with up to five management areas per species. There is only one logbook across all fishing sectors, streamlining data collection. All data collected, while managed by a private company, remains the property of businesses or vessels from which it is collected. Skippers and crew have also been trained to take on the role of on-board observers as the data can be validated through electronic monitoring and this brings down the cost for operators.

Wayne Dredge says learning about the traceability built into the IGF in Canada was a light-bulb moment.

“Australian fisheries are environmentally sustainable but don’t do enough to prove it,” he says. Fishers unload at a port and the fish they catch makes its way to consumers through myriad wholesalers and retailers. They are invisible to their consumers and this disconnect translates into a loss of social licence and understanding of their sustainability credentials and professionalism.

Management in the EU

In contrast to the positive turnaround for the IGF in Canada, Wayne Dredge’s Nuffield report contends that EU fisheries provide an example of regulation imposed without industry consultation and guided primarily by political objectives.

EU fish stocks are a shared resource between the 28 member states, each of which has ownership over 12 nautical miles from their coastline. All other waters out to the 200 nautical miles line, which was the traditional exclusive economic zone for each member, is now common water that can be accessed by all EU fishing vessels who possess licences and quota for the respective region.

Member states all receive an annual quota for these common zones that is based on historical catch. The quotas, along with technical measures and input controls decided by the EU governance bodies, are the result of political rather than scientific processes.

Wayne Dredge says the discard ban imposed in 2014 is an example of those politics combined with restrictive regulations that make innovation impossible.

The discard ban ensures that all fish are retained on board, landed and counted against individual quota holdings. Fish that cannot be consumed by humans must be sold for fishmeal.

The theory behind the discard ban is that it will operate as an incentive for greater selectivity in fisheries. However, the technical measures that mandate specifications such as mesh size mean that fishers are without the flexibility that would allow them to achieve the improved selectivity the discard ban aims to ensure. This is a good example of rules inhibiting innovation and stopping fishers from making changes that achieve goals and their objectives.

The catch from an electric pulse trawl.

The catch from an electric pulse trawl.Photo: Wayne Dredge

With a lack of uniformity in accountability, compliance and transferability of rights, Wayne Dredge contends that the EU fishery can be compared with Australia’s complicated system of competing management regimes.

Change in Australia

By seeing what works and what does not work in other regions, Wayne Dredge’s report makes a range of recommendations for Australia’s management system. In addition to a comprehensive review to examine conflicts and overlaps, he says that the case in Canada shows that 100 per cent electronic monitoring and a standard data collection platform are central to a management system that truly ensures the welfare of both fisheries and fishers.

While he admits that the recommendations he makes are politically unpalatable and thus challenging, he says the international case studies demonstrate how some of these things can be achieved.

Foremost among these is to ensure that reform should be led by the fishing sector itself. He says this can be achieved by providing a choice to the sector to develop a solution themselves or have one imposed on them by management, something that all fishers will be keen to avoid.

“The first need would be acceptance of the need for reform and this acceptance is not limited to just those within the fishing industry.

Fishery managers, and indeed politicians whose portfolios cover fisheries, must also concede that while Australia’s fisheries are in good shape environmentally, the way in which they are administered is outdated, counterproductive, inefficient and in contrast to a more ecosystem-based model.

“Without serious Commonwealth and state reform it is likely that conflicting political objectives will continue to hinder innovation and cause a greater loss of human talent from the industry than we have already seen.”

Stand up, be seen

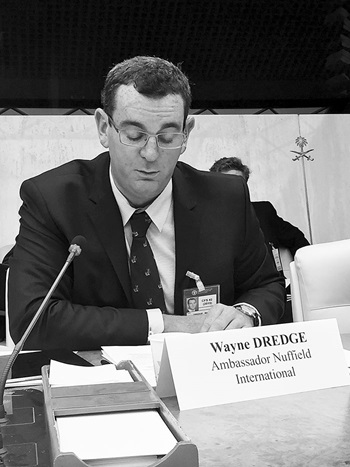

Wayne Dredge

Wayne Dredge In the course of his Nuffield tour, Wayne Dredge was invited to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) and attended its 2015 Committee on World Food Security meetings – a series of policy discussions about food security.

There he found himself the only person with a business background in fisheries and certainly the only fisher attending.

“The discussion was so far removed from what the real issues are facing farmers and fishers globally that I was extremely disillusioned by the entire process.”

Yet he says this experience led to a breakthrough realisation that was really the defining moment of his entire Nuffield journey.

“If you are not part of the discussion, then you are also not part of the solution and the discussion only takes place between the people who bother to turn up.”

He says he is continually surprised at how people, including farmers, dismiss the role of fisheries in the context of food security.

This visibility issue has ramifications for fishers and fishing at high-level discussions such as the Committee on World Food Security, but also in other ways. Consumers often have little understanding of the fishers who catch their fish, or their work practices. In Australia, despite the majority of fisheries being well managed and sustainable, this lack of visibility has harmful consequences to fishers’ image and their wellbeing.

Wayne Dredge says the loss of human capital when young people choose careers other than agriculture or fisheries is one of the greatest issues facing the future of food security. For his part he is using his exposure at the FAO to push for policies that encourage young people to enter agriculture and fisheries-related careers.

He remained involved at the Committee on World Food Security in 2016 and 2017, and recently negotiated a partnership between the FAO and Nuffield to allow young people from both the agriculture and fishing industries to take part in more international events and even undertake short-term internships within the FAO at its offices around the world.

“One issue producers all around the world face is that our governments sign UN policy agreements that our nations then begin to implement within their own countries that impact on producers.

“While these initiatives are well intentioned, they are most often formulated without input from the people they affect the most. It is critically important that more people from small and medium agricultural or fishing enterprises become engaged in these processes,” he says.

Wayne Dredge’s Nuffield Scholarship was sponsored by the FRDC.

FRDC Research Code: 2016-407

More information

Wayne Dredge, dredgewa@gmail.com