Large datasets and modelling tools are creating new capability for both the sustainable harvest and conservation of seabed ecologies

By Gio Braidotti

As part of a global trawl best practice project an international team of researchers that includes several Australians has succeeded in compiling data that outlines the degree of impact of bottom-trawling fishing gears on the world’s seabeds.

The researchers are also developing new modelling tools to estimate seabed disturbance and recovery over large spatial areas. These tools can be used to assess the condition of even ‘data-poor’ fisheries.

Towed bottom-fishing gears are used to catch fish, crustaceans and bivalves living in, on or above the seabed; they include otter trawls, beam trawls, towed (scallop) dredges and hydraulic dredges.

Combined, these fishing methods accounted for almost one-quarter of global seafood landings between 2011 and 2013.

Trawling forms the basis of numerous commercial industries – including Australia’s wild-caught prawn industry – but the gear is used near seabed fauna that is critical to the health of marine ecosystems. For example, seabed invertebrates help oxygenate the seabed, break down organic material, and provide habitat structure and food for other organisms.

Global analysis

The global data compilation was undertaken by an international team of researchers from the UK, the Netherlands, the US, Argentina, Australia and the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United

Nations. Included were Nick Ellis, Tessa Mazor and Roland Pitcher from CSIRO Oceans and Atmosphere in Brisbane, Australia.

In total, 70 studies were compiled and analysed to estimate trawling impact on unprecedented spatial scales.

Twenty-four studies accounted for the spatial extent, frequency and temporal variability in fishing activity, and provided estimates of recovery rates on fishing grounds. Forty-six studies provided estimates of the mortality of biota (sea life).

Most of the compiled data was sourced from studies undertaken in temperate zones and concentrated in north-western Europe and the north-eastern US.

In a jointly written scientific paper, the researchers reported that otter trawls caused the least depletion, removing six per cent of biota per pass and penetrating the seabed on average down to 2.4 centimetres.

In contrast, hydraulic dredges caused the highest impact, removing 41 per cent of biota and penetrating the seabed on average 61 centimetres.

“We need to view these results in the context of the footprint of each of these activities,” CSIRO marine ecologist Roland Pitcher says.

“Otter trawling has the least impact per trawl pass, and is also the most widely used bottom fishing gear so that its effects are more widespread than are those of more specialised fishing gears such as hydraulic dredges.”

The researchers found that the majority of benthic life took 1.9 to 6.4 years to return to 95 per cent of its pre-trawling amount Roland Pitcher, CSIRO marine ecologist, says the new modelling tools provide objective analysis of the trade-offs between harvesting fish and the wider ecosystem implications, even for fisheries with limited information.

Because of this new capability, the modelling is being adopted by the Marine Stewardship Council as an assessment tool for the sustainability certification of fisheries.

“The results have global policy relevance for conservation and food security policy development. This is because they enable an objective analysis of the efficacy of different harvesting methods of harvesting food from the ocean to be considered in the light of the wider ecosystem effects of such activities on the marine environment,” the research team concluded in their report.

In Australia, trawl catches account for about 24 per cent of the total wild catch, with nearly 86 per cent of all marketed prawns caught this way as well as 19 per cent of other demersal species.

Of the trawling methods used in Australia, otter trawls dominated and accounted for 99.9 per cent of the trawl footprint. Dredging for scallops accounted for the remainder.

The analysis was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS) in August 2017 (Volume 114, number 31).

In another paper produced by the same international trawl best practice project, the analysis focused on Australia’s exclusive economic zone (EEZ), a marine area of 8.14 million square kilometres.

Focus on Australia

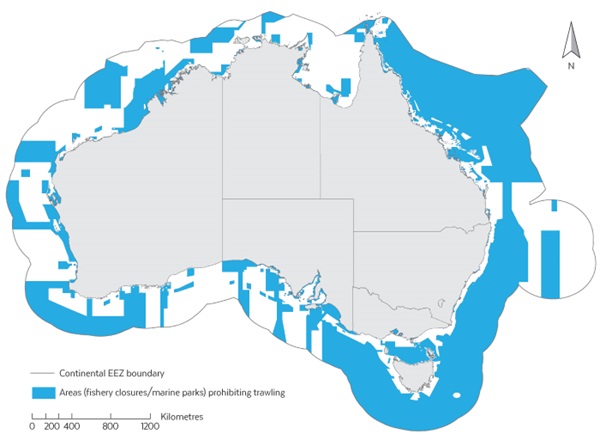

Map showing the continental EEZ boundary and areas (blue) prohibiting trawling.

Map showing the continental EEZ boundary and areas (blue) prohibiting trawling. Source: CSIRO

The current trawl footprint was found to be 1.1 per cent of the entire EEZ, with 58 per cent protected from trawling by closures and reserves (see map) – a much higher proportion of protection than in most other countries.

Seabed biodiversity survey data was collated to build a large-scale distribution of seabed communities and to assess exposure to trawling in the Great Barrier Reef region, the Gulf of Carpentaria,

Torres Strait, south-east Australia, Great Australian Bight and Western Australia.

“We found that most regional seabed communities around Australia have higher protection (average 38 per cent) than exposure to trawling (average seven per cent),” CSIRO lead author Tessa Mazor says.

“An average of 55 per cent of each community was neither protected nor trawled.”

The study also identified the need to improve information on the presence and distribution of the more sensitive habitat-forming benthos types, such as long-lived species that may struggle to recover after trawling.

These are of interest to stakeholders as markers of seabed health.

The authors concluded that: “These results help identify regions and taxa that may be at greatest potential risk from trawling and support managers to achieve balance between conservation and sustainable industries in marine ecosystems.”

Roland Pitcher says that the next step is a national assessment of the sustainability of seabed habitats and communities.

Australia’s trawling footprint can be explored using the trawl footprint and swept area in the interactive table and maps at the State of the Environment website.

Research voyage to investigate long-term trawl impact

From the 1950s Australia’s North West Shelf was a focus for national and international trawling. This reached a peak when Taiwanese vessels landed about 40,000 tonnes of fish from the area in 1974.

When catches began to decline in the 1980s, CSIRO sent a team of scientists to assess the impact on seabed organisms and the region’s recovery from intensive trawling.

At the time, the research team found it was too early to make a full assessment of recovery rates. However, it was able to ascertain that the reductions in targeted fish species were associated with a loss of three-dimensional seabed habitats.

Thirty-five years later, in October 2017, the Marine National Facility research vessel Investigator undertook a research voyage, supported by FRDC funding, to reassess and compare those early findings.

Foreign vessels have not trawled in the region since 1989. The current Australian fishery is operated over a much smaller area with fewer vessels, and in 2015 caught 1779 tonnes. CSIRO researcher John Keesing is chief scientist on the voyage and says the absence of trawling for many years on parts of the North West Shelf makes it an ideal place to carry out this research.

“To understand the recovery, we will look at the species and size of fish in the region, the types of organisms living on the sea floor and the amount of phytoplankton and zooplankton in the water, which along with providing food for fish are key indicators of productivity in a region.

“How animals on the seabed recover from trawling is an important global issue and the research will provide the latest science to both Australian and international management agencies.”

Findings from the study are expected to be available later this year and will be shared with industry, management agencies and the general public.

FRDC Research Code: 2017-038

More information

Global analysis of depletion and recovery of seabed biota after bottom trawling disturbance

Trawl exposure and protection of seabed fauna at large spatial scales