Australia’s marine territories are double the size of its land mass, and protecting these resources from illegal fishers – both foreign and domestic – requires constant vigilance and collaboration between government forces and fishers themselves

Aerial surveillance spots a Vietnamese fishing boat targeting sea cucumber, one of 14 vessels apprehended by Australian forces in 2016-17.

Aerial surveillance spots a Vietnamese fishing boat targeting sea cucumber, one of 14 vessels apprehended by Australian forces in 2016-17.Photo: AFMA

By Catherine Norwood

The deliberate sinking of foreign fishing vessels as dive wrecks – or scrapping or torching them ashore – makes for a dramatic climax to the prosecution of illegal foreign fishing in Australian waters.

Along with jail terms, fines and the confiscation of catch and equipment, the destruction of boats is the culmination of often exhaustive operations targeting illegal operators across national, state and territory jurisdictions.

But just as important, if not more so, is the deterrent effect of these highly visible policing and compliance efforts.

A suite of operational measures, including policing and education programs, helps to prevent the level of activity that would jeopardise fish stocks, particularly in the case of high-risk species and locations.

Over the past few decades efforts across all jurisdictions have helped to ensure that the overall volumes of catch taken illegally have remained low enough that they can be accounted for as part of natural mortality numbers within stock-assessment modelling.

Protecting our borders

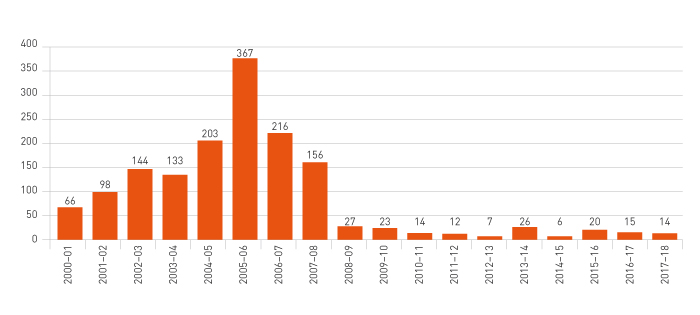

In the 2000s the number of foreign vessels fishing illegally in Australian waters was steadily increasing, reaching a peak in 2005‑06 when 367 vessels were apprehended, most of them across northern Australia.

“That’s more than one a day,” says Peter Venslovas, general operations manager at the Australian Fisheries Management Authority (AFMA). “And there were many more that we just didn’t have the resources to pursue,” he says.

Most vessels were small (less than 10 metres) but the large numbers had potentially serious impacts on the sustainability of fragile northern fisheries.

Since 2005, however, there has been a dramatic decline in incursions – just 14 vessels in 2017-18 (Figure 1) – attributed to the Australian Government’s more active enforcement campaign.

To reduce illegal fishing in Commonwealth waters AFMA works closely with Australian Maritime Border Command – a multi-agency taskforce within the Australian Border Force – which coordinates surveillance and monitoring for a host of maritime threats, including poaching.

Incursions in the north are most commonly from neighbouring countries such as Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and, recently, Vietnam. However, it’s international demand that drives up both the prices and consequently the risks that fishers are prepared to take.

The detrimental effect could be crippling, Peter Venslovas says. In 2016-17 there was a spike in illegal activity, with 14 fishing vessels from Vietnam apprehended. All were targeting sea cucumber, and their combined catch of 64 tonnes was greater than the annual total allowable catch (TAC) of 55 tonnes for licensed Australian fishers in the Commonwealth fishery.

Peter Venslovas says ongoing poaching on this scale could quickly cause the sea cucumber fishery to collapse, but enforcement efforts, including the seizure of boats and catch, and jail terms for crew have since stopped the Vietnamese incursions.

Enforcement is just one of the strategies AFMA uses. In-country education becomes an important follow-up step. “We visit the key ports where illegal fishing vessels are coming from, such as Indonesia and Vietnam, and explain to fishers what happens if they are caught in Australian waters,” he says.

Australia also works directly with neighbouring governments to improve their ability to monitor and control fishing activities in their own waters, and works collaboratively with international partners to strengthen regional fishing frameworks and the exchange of information to address illegal fishing on a larger stage.

Peter Venslovas says while enforcement efforts are paying off for Australia in northern waters there remains considerable activity outside Australia’s maritime border. Maritime Border Command mapping of activity shows hundreds of vessels sitting just across the imaginary line that represents Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone. “It’s crucial we maintain our capacity to conduct patrols. We still do boardings at sea to educate operators about coming across the border, and have fisheries officers on Navy and Border Force patrol boats.”

FIGURE 1 Foreign fishing vessel apprehensions financial years 2000-01 to 2017-18.

FIGURE 1 Foreign fishing vessel apprehensions financial years 2000-01 to 2017-18.Source: AFMA

Southern strategies

The strategy AFMA deploys in the north is very different to that used in the Southern Ocean.

Since the 1990s vessels have targeted Patagonian Toothfish (also sold as ‘Chilean seabass’), seriously jeopardising international toothfish populations. In 1997 there were more than 30 ‘rogue’ boats identified in the Southern Ocean, including in Australian waters. These were large, industrial-scale vessels with a massive capacity to take fish, and to make the operators millions of dollars.

Since then, licensed fishers have created the Coalition of Legal Toothfish Operators to work with Australian and other government forces and NGOs to report and help apprehend poachers. It’s the kind of alliance essential in international fisheries to provide the level of enforcement needed to support management that will protect the long-term sustainability of fisheries resources.

Australian Government authorities have successfully prosecuted the operators of at least nine vessels; sinking two boats as dive reefs off the Western Australian coast and sending others to ship-breaking yards. Many of the vessels were found to have Spanish connections, and the largest syndicate, known as the Bandit 6, was pursued for more than a decade before finally being put out of action. Bandit 6 included the FV Thunder, famously scuttled by its own captain after a 110‑day pursuit by Sea Shepherd vessels in 2015.

Peter Venslovas says the original tactic of pursuit and prosecution in the Southern Ocean evolved into a strategy that focused on dismantling the business model for these illegal fishers.

This involves agreement to close ports where illicit catch could be landed and working with international authorities to prosecute the beneficial owners, which has been successful in virtually eliminating illegal activity in the south.

Much of the media focus is on the limited number of foreign incursions in Commonwealth waters. But with 197 kilometres to cross from the boundary of Australia’s Exclusive Economic Zone to reach state and territory water, foreign incursions aren’t an issue inshore.

Eastern Rock Lobsters were the target of organised criminal activity in NSW that resulted in jail terms for those prosecuted.

Eastern Rock Lobsters were the target of organised criminal activity in NSW that resulted in jail terms for those prosecuted.Photo: NSW Department of Primary Industries

Domestic fisheries

On a domestic level illegal fishing crosses both commercial and recreational sectors.It also includes organised criminal activity by elements outside the fishing community.

The key areas of domestic illegal activity include:

- commercial fishers misrepresenting their actual catch (deliberately or not);

- recreational fishers failing to comply with regulations such as bag and size limits;

- recreational fishers selling their catch; and

- deliberate criminal activity (although this is not an extensive problem).

A large variety of species are targeted, however, high-value abalone and rock lobster, which are both easily harvested using minimal gear, are easy targets.

Surveillance and compliance are crucial across state and territory jurisdictions to address these activities, and have led to several successful prosecutions encompassing commercial and recreational fishers, as well as other players in the seafood supply chain.

In NSW the courts handed down a two-year jail term for a NSW commercial fisher who illegally re-used rock lobster tags as part of an organised black market operation. Two other people involved in this operation, including a cook at a function centre that received the illegal catch, received 12-month suspended sentences. Fines imposed in the case totalled $2 million.

NSW Department of Primary Industries director of fisheries compliance, Patrick Tully, says the courts are taking fisheries cases more seriously, with harsher penalties being applied in recent cases. He says while illegal fishing threatens fisheries resources, it also undermines legitimate fisheries users, including the investment of commercial fishers and the value of their licences and quota.

In Victoria, Operation Torpedo led to the arrest of a fish shop owner and two associates in January 2018 for allegedly laundering recreationally caught fish through the shop and “dealing in the proceeds of crime”. The shop owner’s 7.5-metre boat, valued at $150,000, and a truck were seized, along with fishing gear worth more than $10,000.

In another Victorian case two men were fined more than $17,000 in June and forfeited their boat, a car and other equipment after being convicted on charges of deception and illegal fishing. The pair posed as commercial fishers, taking illegal catch from the Gippsland Lakes and selling it in Melbourne.

Director of the Victorian Fisheries Authority, Dallas D’Silva, says while the sale of recreationally caught fish undermines the legitimate commercial fishing sector it also creates potential public health issues. “These fish aren’t subject to the same food safety standards and scrutiny as commercial fish,” he says. “They put the health of customers and the reputation of the retailer at risk.”

He says tips from the public via the state’s ‘13FISH’ hotline were important in assisting compliance efforts, with thousands of calls received each year and “some fantastic apprehensions”.

Manager of compliance statistics and systems for WA’s Department of Primary Industries and Regional Development, Tim Green, says there is clearly some hard-core criminal activity in fisheries. While it was not an extensive problem, it was enough of an issue to warrant a special enforcement team to deal with it in WA, and in other states.

Tim Green works with the compliance subcommittee of the Australian Fisheries Management Forum, an informal network of government managers from across the country, and has led FRDC-funded research to identify indicators for better compliance outcomes.

He says quantifying illegal fishing, and the impacts on resources, remains an ongoing challenge for governments.

“It is difficult to use indicators such as the number of fines issued, or the dollars spent on enforcement, because these may not reflect activities that directly impact on the sustainability of fisheries themselves,” he says.

“For example, illegally pulling someone else’s lobster pots has been a high priority issue in WA, but it’s an issue of public amenity and equity between fishers rather than ecology – at least in the short term.

“But we have strong legislation, good compliance risk-management processes and capable, professional compliance officers. We also have good partnerships with fishers and their representative bodies, which helps to ensure, based on all the indictors we have, that levels of illegal fishing are contained or minimised.”

Report illegal fishing

Commonwealth fisheries

CRIMFISH hotline, 1800 274 634, intelligence@afma.gov.au

submit a report

Australian Capital Territory

Crime Stoppers hotline, 1800 333 000

New South Wales

Fishers Watch, 1800 043 536

submit a report

Northern Territory

Fishwatch hotline, 1800 891 136

or report via the NT Fishing Mate app

Queensland

Fishwatch hotline, 1800 017 116

South Australia

Fishwatch hotline, 1800 065 522

Tasmania

Fishwatch hotline, 0427 655 557

Victoria

13FISH, 13 3474

Western Australia

FishWatch, 1800 815 507