A new report maps the successful characteristics of Indigenous initiatives to develop fisheries

By Catherine Norwood

For Indigenous communities wanting to develop their fisheries resources, a new step-by-step approach has emerged from a five-year research project, providing guidance for communities, government fisheries managers and potential business partners.

The FRDC’s Indigenous Reference Group (IRG) initiated the project ‘Building the capacity and performance of Indigenous Fisheries’, released in June 2018, which analysed seven initiatives across six fisheries jurisdictions.

The principal investigator for the project, Ewan Colquhoun from Ridge Partners, says around Australia fishery assets contribute only a small amount, directly or indirectly, to the total economic wellbeing of Indigenous communities.

“Of those communities seeking economic development, many are unaware of the true latent economic value of their fishery assets,” he says. “Looking beyond customary uses, most communities have only limited engagement in fishery economic activity, and therefore underutilise their fishery resources.”

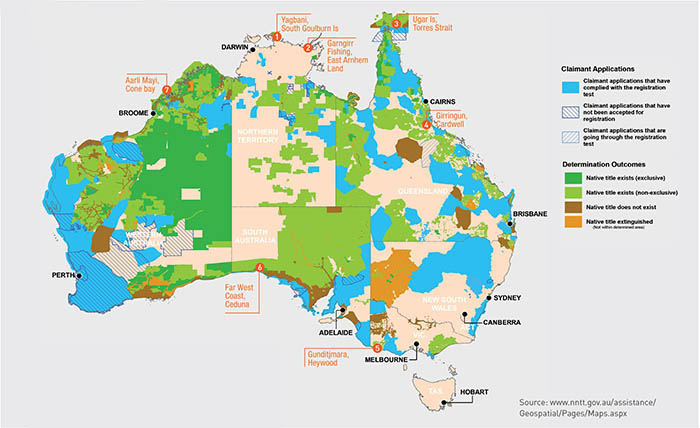

Indigenous Australians own or have legislated rights under various exclusive and non-exclusive Native Title and rights to 40 per cent of the Australian land mass. Where adjacent to marine coastlines and river catchments, these rights extend to certain fishery resources as well (see map above). But Ewan Colquhoun says these rights are not leading to beneficial outcomes for Indigenous communities.

As part of the IRG project, seven case studies were developed from face-to-face discussions with community participants about actual or proposed fishery initiatives to identify processes that have worked and potential barriers to be overcome.

Ewan Colquhoun

Ewan ColquhounPrincipal investigator

The Indigenous fishery community is the core stakeholder in the quest to boost the capacity and performance of Indigenous fisheries.

Ewan Colquhoun says communities vary greatly in their understanding of their fishery assets and in their engagement with, access to and use of marine or freshwater fishery resources. “This diversity compounds the economic complexity that community leaders, investors and research managers face

in seeking to boost fishery capacity and performance.”

The report has come at an ideal time for Shane Holland, who has stepped into the role of traditional fisheries manager fisheries and aquaculture created at Primary Industries and Regions SA last year. He is also a member of the Indigenous Reference Group.

“It’s really useful for us as managers to understand what works and why,” Shane Holland says. “In South Australia we have Indigenous communities that want to develop business opportunities from fishery resources. This report will help us to provide advice to those communities to enhance the success of their initiatives.”

Ewan Colquhoun says each community must decide for itself whether it wants to pursue the economic development of its fishery resources. For some communities, the potential to provide jobs, skills and meaningful activity, particularly for young people, may be the primary motivator, rather than financial returns.

Steps to success

From the case studies, the project has identified six attributes for an Indigenous fisheries venture that provide a sound foundation for success.

- Ensure there is formal community cultural governance in place, which establishes a leadership platform and helps to clarify the fishery assets available for potential development. This should include registration with the Office of the Registrar of Indigenous Corporations.

- Separate the corporate governance of a business initiative from the community’s cultural governance structures. Corporate governance provides independent financial and risk management for a commercial enterprise, but the aspirations of the enterprise should also align with the aspirations of local community governance.

- Provide access to new Indigenous and non-Indigenous knowledge. Case studies indicate that this may be provided through mentoring, action learning, formal courses on and off-site, joint ventures, collaborations and supply chain relationships.

- Incorporate microbusinesses within the business venture. This provides a way to empower families, clans and individuals, allowing each to make their own decision to specialise, invest, learn and contribute their own labour and resources into ventures that create economic returns for the community, their respective family or clan, and themselves.

- Develop a formal business plan for the first three to five years, which is reviewed regularly thereafter. The planning process and the document are vital to defining and securing commitment from community leaders and third parties (chain partners, buyers, governments) and outcomes.

- Establish a professional management team to lead the venture, with authority from its own board and from the community to implement an agreed business plan and strategy. The management team should report progress to owners and community stakeholders.

Case studies

The case studies examined for the ‘Building the capacity and performance of Indigenous Fisheries’ project include both operational and proposed fisheries economic initiatives.

- In the Goulburn Islands in the Northern Territory, the five clans of the Warruwi Community established the Yagbani Aboriginal Corporation in 2011 as a not-for-profit organisation run by a joint committee of clan representatives. Fisheries activities are part of the corporation’s broader community initiatives and include ranching, harvesting and providing first-stage processing for Sandfish (Sea Cucumber), establishing an agreement in 2015 to supply Tasmanian Seafoods Pty Ltd. There have been two successful harvests and further development is underway. The corporation is also involved in research trials for Blacklip tropical oysters (Striostrea mytiloides) and fluted giant clam (Tridacna squamosa) aquaculture, in conjunction with the Northern Territory Fisheries aquaculture unit.

- Also in the Northern Territory, the Yolngu people of the East Arnhem Communities established the Garngirr Fishing Aboriginal Corporation in 2013 as a commercial cooperative to harvest and distribute finfish and crustaceans. This venture has moved from a pilot project to a stand-alone business, with ongoing support from Northern Territory Fisheries. Its strategic plan includes a proposal to purchase commercial seafood licences to expand production.

- In the Torres Strait, members of the Ugar Island Community own and operate the Kos & Abob Fisheries (KAF) Torres Strait Islander Corporation with volunteer management and staff. The business harvests, processes and sells Sea Cucumber and finfish to markets in Cairns. A new business plan outlines a path to establish a professional management team and progressively increase harvests of under utilised available commercial species, working with other eastern zone island communities and the Australian Fisheries Management Authority.

- Based between Cairns and Townsville in Queensland, nine tribal groups are represented in the Girringun Region Indigenous Protected Area (GRIPA) governed by the Girringun Aboriginal Corporation. Established for 20 years as a not-for-profit, the corporation has stable and successful governance in place to advance participation of traditional owners in resource management and community health and wellbeing. Its current management plan incorporates the development of marine and fishery assets, with three licence options being considered. This would build on its successful sea ranger program, provide employment opportunities and create a branded Girringun sea country product.

- In south-west Victoria, the Gunditj Mirring Traditional Owners Aboriginal Corporation provides the overarching governance for the affairs of the Gunditjmara people. It has two separate fishery ventures based on native eel and pipi fisheries in development. One proposal is part of the larger regional Budj Bim Master Plan to re-establish customary eel fishing at Lake Condah, where engineered stone weirs provide a record of eel farming from more than 6600 years ago. This system has been nominated for World Heritage status. Indigenous eel fishing would enhance the developing Budj Bim Indigenous tourism experience. Investigations are also underway into a customary or commercial pipi fishery at Discovery Bay in south-west Victoria.

- South Australia’s Far West Coast Aboriginal Corporation was officially established in 2013, representing six clans. However, pre-existing Indigenous organisations had already established professionally run commercial enterprises for the local clans, including mining agreements and the leasing of mine equipment. Three new ventures are being planned to generate income that will support the aims of the corporation and provide for its members’ cultural, social and economic needs. These new ventures in development include recreational fishing tours, a seafood tourism trail, and investment in employment opportunities in commercial fishing and downstream seafood processing.

- The Kimberley Saltwater Country people in Western Australia’s northern region have come together to establish a large-scale commercial aquaculture venture that aims to produce high-quality seafood for world markets. Partners in the joint venture are the Dambimangari, Bardi Jawi and Malaya Aboriginal Corporations, representing the region’s three clans, and the Maxima Opportunity Group, owned by the Hutton family. Each partner has a 25 per cent share in the Aarli Mayi Aquaculture Project Joint Venture. In 2016 the venture was awarded a new aquaculture licence and lease in the Kimberley Aquaculture Development Zone to produce up to 5000 tonnes of finfish a year, and the business proposal has undergone a full feasibility study. The first harvest is expected in 2020.

FRDC Research Code: 2013-218

More information

Ewan Colquhoun, 07 3369 4222

ewan@ridgepartners.com.au

The Indigenous Estate.

The Indigenous Estate.