Preventing plastic from entering the marine food chain and maiming ocean wildlife is driving efforts to reduce, reuse and recycle

Story Catherine Norwood

Photos Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry

Plastics and rubbish collected during beach clean-ups by members of Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association.

A commitment to making the 2019 national industry conference, Seafood Directions, a plastic-free event provides an important opportunity to raise awareness about plastic pollution in marine environments.

According to members of last year’s National Seafood Industry Leadership Program (NSILP), it is also an opportunity to demonstrate what positive action the seafood sector can take to make a difference.

Fishers are significantly affected by plastics in the ocean – even though it is not an issue they are solely, or even largely, responsible for, says Michael Hobson, a commercial fisher and food service operator at Port Albert, Victoria.

Bags of rubbish collected by members of Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association.

He was a member of the NSILP Plastic Free Fish project team last year, along with Adrianne Laird from the Northern Prawn Fishery Industry (NPFI) Pty Ltd, Toby Jeavons from the Victorian Fisheries Authority and Brad Callcott from Pacific Reef Fisheries.

The team’s research identified the extent of the plastic pollution issue and potential impacts for the Australian seafood sector.

A global issue

Recent studies have estimated that approximately eight million tonnes of plastic end up in the world’s oceans every year. This contributes to the deaths of the marine animals that become entangled. Plastic can also find its way into the stomachs of seabirds, sea mammals, fish and other marine life, affecting the entire food chain.

The attributes of plastic that make it so attractive as a material, including its durability, are also the attributes that make it so dangerous and long-lived. Products might break down, but the plastic itself remains in the environment. Greenpeace researchers have found plastics in water and snow samples in areas as remote

as Antarctica.

CSIRO research has identified that almost three-quarters of the rubbish on Australia’s coastline is plastic, and that it comes from Australian sources. Research from the Australian Institute of Marine Science has also reported widespread microplastic contamination of waters in north-western Australia. More recently, a study of juvenile Coral Trout from the Great Barrier Reef has identified that tropical fish are ingesting both plastic and non-plastic marine microdebris (particles of less than five millimetres).

With mounting local and international evidence about the impacts of plastic and its infiltration of the seafood food chain, NSILP’s Plastic Free Fish team worked with OceanWatch Australia to incorporate efforts to reduce plastic as part of the OceanWatch ocean pledge.

Local initiatives

Oyster baskets waiting for recycling.

Toby Jeavons says the aim is for individuals, organisations and businesses in the seafood industry to take the pledge below, reduce their reliance on plastic, recycle plastics where possible and seek alternatives to plastic products.

The team has put out a call to industry to take this pledge:

“The seafood industry is directly dependent on the health of the marine environment and sustainable fish stocks. Reducing the use of plastic within industry and diverting plastic from landfill strengthens our commitment to environmental responsibility, increases our contribution to protecting the future of global fishery resources, and improves our social licence to operate. The Australian seafood industry can lead by example and add to the global momentum of plastic use reduction.”

In addition to a plastic-free 2019 Seafood Directions, the team is working with the organisers of other seafood industry events to reduce plastic use.

Brad Callcott has initiated an independent plastic audit at Pacific Reef Fisheries, where he is operations manager of the aquaculture operations in Ayr, Queensland. He hopes this will identify areas where the business can reduce plastic use, and perhaps provide a first step in creating a framework to help other businesses to assess their own plastic use and alternatives.

Recycling options

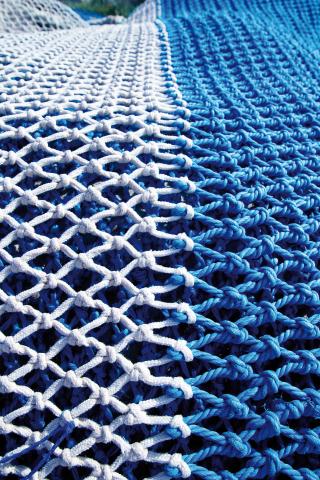

Logistical issues often prevent nets from being recycled.

“We are looking at the packaging of our seafood and seeking alternatives to virgin plastics,” Brad Callcott says. “We also know that the bags used for aquaculture feed are an issue.”

These were being recycled in China, he says, but Pacific Reef has been stockpiling them since China’s decision last year to ban this type of material for recycling.

“We’ve purchased a baling machine for feed bags, which has reduced the volume of this waste by about 90 per cent, making it more easily transported to a recycler or to landfill if necessary. We’re working to find a solution and talking with our feed supplier who is also keen to find a recycling solution.”

In Victoria, Michael Hobson says that since taking part in the NSILP project, he has audited his own restaurant and fish-and-chip shop at Port Albert. His businesses made changes that include swapping from polystyrene takeaway food containers to cardboard boxes and paper bags.

He says it has proven much more difficult to eliminate the plastic that comes from their suppliers.

“There’s not really the willpower in the food service sector to change, and often it is difficult to find alternatives to plastics. We’ve really struggled to replace the plastic containers for our homemade tartare sauce, for instance.”

Adrianne Laird says the NPFI has signed up to the OceanWatch ocean pledge. The industry organisation will work to ensure its events, be they board meetings or stakeholder workshops, are plastic free – no plastic for catering, for example.

“We’re also looking at how we might be able to recycle fishing nets,” she says. “But logistically it’s difficult to bring together nets from our ports in Karumba, Darwin and Cairns for recycling. We’ve found a company based in Tasmania who can recycle the nets and other plastics but the distances make it difficult.” “The NPFI is also a signatory to the Global Ghost Gear Initiative and, when possible, our operators retrieve ghost gear they encounter during the fishing seasons.”

From a personal perspective, Adrianne Laird says working on the project opened her eyes to the extent of the plastic problem in Australia, and globally.

“We can’t completely eliminate plastic use in the industry, but we can reduce our use and recycle more.”

At home she has introduced cornstarch garbage bags, steel straws and reusable produce bags, and returns soft plastics to the supermarket for recycling.

“The issue is so huge it can be disheartening,” she says. “But I’m proud of the efforts we’ve made, and I think it all makes a difference. And I believe Australia’s seafood industry can lead the way and be an example of the changes that can be made.”

Plastic use review

The Sydney Fish Market recycles its iconic blue crates.

FRDC has previously funded a desktop review (2004-410) into the feasibility of reducing plastic use in the seafood industry. This research, undertaken by OceanWatch, found high levels of plastic use in the commercial wildcatch sector, including equipment such as nets, lines and floats. However, it also identified that a high number of fishers and fishing co-operatives had already introduced plastic and waste minimisation initiatives in conjunction with efforts to reduce costs.

The most difficult hurdle, the report said, was disposal of plastic waste products. This was particularly the case in the post-harvest sector, including seafood wholesalers, retailers and the general public as consumers of seafood. Opportunities for plastic alternatives in the seafood industry were identified as part of this project, outlined in Table 1.

Table 1: Typical plastic items used in the seafood sector supply chain and possible alternatives

| Plastic item | Recyclable | Possible scrap value | Alternatives | Possible alternatives available |

| Polyethylene and polypropylene | • | • | Recycling options only | |

| Monofilament lines | • | • | Recycling options only | |

| Ropes | • | • | Recycling options only | |

| Buckets (consumable containers) | • | • | Recycling options only | |

| Floats (foam) | • | • | Recycling options only | |

| Floats (plastic) | • | • | Recycling options only | |

| Fish boxes (hard plastic) | • | • | Recycling options only | |

| Tuna bags | • | • | Recycling or re-use options | |

| Tuna mats | • | Recycling or re-use options | ||

| EPS boxes | • | • | • | Coolseal-type boxes |

| Produce bags including bait bags | • | • | Starch-based biodegradable bags | |

| Sheeting | • | • | Starch-based biodegradable bags | |

| Carry bags | • | • | • | Starch-based biodegradable bags. Other degradable bags. Calico bags. Paper bags. Non-woven bags. |

Source: OCEANWATCH AUSTRALIA, FRDC Project No. 2004-410

Recycling in aquaculture

The Fish Shoppe provides a model for fishmongers planning to go plastic free.

In 2017-18 the Tasmanian Atlantic Salmon industry and fish pen manufacturers recycled 637 tonnes of plastics. Local recycler Envorinex remanufactures items such as pipes, feed pipes, stanchions, nets, floats, ropes, feed bags (high-density polyethylene, low-density polyethylene, soft plastics) into new products. Tassal is also moving to 100 per cent recycling of major plastic waste across its Atlantic Salmon farming operations.

The Tasmanian oyster industry began a recycling project in 2018 to develop a method for tackling some existing stockpiles of old equipment and an ongoing industry model. Oyster baskets are proving difficult to recycle, as some components are made from plastics that Envorinex cannot process or have cable ties attached. The industry is continuing

to research options, including mulching before separating plastic types and changing to basket manufacturing.

Supply chain plastics

The Sydney Fish Market (SFM) introduced its plastic-neutral plan in January 2018.

A key initiative is a polystyrene processing machine that recycles 150,000 fish boxes each year, rescuing the equivalent of 100 tonnes of polystyrene from landfill. SFM is also returning its iconic blue fish crates to the manufacturer for recycling at the end of their 10-year life span.

Beach clean-up campaigns

The many beach clean-up initiatives already in place include the adoption of 155 kilometres of coastline in the Port Lincoln area by members of the local aquaculture sector, who conduct beach clean-ups at least once a year. This is part of a proactive community campaign that addresses both general rubbish and debris from the industry.

The clean-ups are coordinated by the Australian Southern Bluefin Tuna Industry Association, and local oyster and mussel producers also take part.

Packaging alternatives

Two Australian innovations are in development to create an out of cold chain alternatives to polystyrene, although neither product is commercially available yet.

Victorian developer Andy Moulynox has patented the Dreamweaver shipper, a fully recyclable material that can be customised to any size. Following successful recycling and temperature trials, he is in the process of raising investment to establish a manufacturing plant.

More information

andy@dreamweaverfoodanddesign.com.au

Queensland-based fishers Tom and Kath Long have also developed the reusable and recyclable TomKat KoolPak (patent pending) for the transport of seafood, which has been successfully temperature tested. Commercial production partners are being finalised.

More information

Retail sales

Land-based waste forms the majority of ocean debris.

At the South Melbourne Market in Victoria,The Fish Shoppe is providing a case study for other retail businesses looking to eliminate single-use plastics, including plastic bags.

Josh Pearce and Renee Vajtauer, who operate The Fish Shoppe, are committed to being fully plastic free this year. They have replaced the plastic bags and sheets used for wrapping and packaging seafood with paper and cornstarch alternatives that are biodegradable and compostable.

The two greatest challenges remaining are slap sheets and oyster trays, Josh Pearce says. The Fish Shoppe sells half-shell oysters in plastic trays, which are made of recyclable plastic. But that means they must be collected for recycling.

A plastic-free alternative would be better; cardboard trays are a possibility.

More information

Josh Pearce

jp@thefishshoppe.com.au

Clothing fibres

Synthetic clothing fibres such as polyester, nylon and acrylic, are among the plastics that have made their way to the most remote parts of the world. The fibres often accumulate in laundry wastewater. Water authorities in some cities, particularly in the Great Barrier Reef catchments, use membrane bioreactors to remove these fibres, which would otherwise end up in our waterways.

At sea, however, there are no water treatment plants to capture the fibres. In one initiative, Austral Fisheries is installing specialised lint filters on vessel washing machines to remove synthetic fibres from the water that is discharged.

Plastic microbeads phased out

Microbeads are small, solid, manufactured plastic particles of less than five millimetres. Often made of polyethylene or polypropylene, they do not degrade or dissolve in water. They have been used in a range of products, including rinse-off cosmetics, personal care and cleaning products, as a cheap alternative for natural exfoliating or abrasive ingredients, such as shell or seed particles.

The Australian Department of the Environment and Energy says microbeads are not captured by most wastewater treatment systems. If they are washed down drains after use, they can end up in rivers, lakes and oceans.

Once in the water, microbeads can damage marine life, the environment and human health. They have the potential to adsorb toxins and can be transferred (along with any accumulated toxins) up the marine food chain.

Several countries, including the UK, the US and New Zealand, have banned plastic microbeads for wash-off personal hygiene products and cleaning agents.

Meanwhile, the Australian Government relied on a voluntary phase-out by July 2018. A report for the Department of the Environment and Energy was released in May 2018, ahead of the voluntary deadline. It indicated that of approximately 4400 supermarket, pharmacy and cosmetic store products inspected, 94 per cent were already free of plastic microbeads or other non-soluble plastic polymers.

FISH mag plastic free

Every few years, the FRDC surveys readers of FISH magazine to see how we are going in the eyes of our readers. In the past, many of our readers have expressed concern that the magazine is mailed in plastic sleeves.

As a marine science organisation, the FRDC has many of the same concerns as our readers in relation to the problem of plastic pollution. The plastic-like sleeves that FISH magazine is mailed in are actually made from a trademarked, degradable, plastic-like film called biowrap.

It has the durability and strength of plastic, but is completely degradable and ultimately breaks down to water, carbon dioxide and a small amount of biomass in the presence of oxygen.

It can also be recycled prior to degradation.

You can find out more about biowrap here.

More information

Brad Callcott

brad@pacificreef.com.au

Michael Hobson

portalbertwharf@bigpond.com

Toby Jeavons

toby.jeavons@vfa.vic.gov.au