Can collaboration between fishers and the seafood supply chain help the underrated wild-caught Australian Salmon find a place in a consumer market dominated by a red-fleshed import?

Story and photos Catherine Norwood

Purse seined Australian Salmon from Lakes Entrance, Victoria, iced at the point of harvest.

Purse seined Australian Salmon from Lakes Entrance, Victoria, iced at the point of harvest. Australian Salmon’s image problem is twofold. One is its poor reputation as a fresh fish offering. The other is its unfavourable comparison with the market-leading Atlantic Salmon. For commercial fishers, both issues have contributed to falling demand and prices so low the fish is hardly worth catching.

But chefs have been known to sing the praises of Australian Salmon unprompted. Speaking at the Slow Fish Festival in Melbourne earlier this year, Oliver Edwards of the Aristologist restaurant in the Adelaide Hills said it was his all-time favourite fish to barbecue. At the same event, former chef and food writer Matthew Evans praised the fish as “a total joy”. It was the perfect curry fish, he said, and with the right handling could even be served as sashimi.

Australian Salmon have a pinky-brown coloured flesh when raw, which turns pale – almost white – when cooked. They are more like herring than salmonids and the Australian Herring (Arripis georgianus), also known as Tommy Ruff in South Australia, is a member of the same family.

Fishers’ challenge

During the past decade, the FRDC has invested in several research projects to identify ways to make better use of Australian Salmon. It is officially designated ‘sustainable’ in the 2018 Status of Australian Fish Stocks Reports, and it could be harvested in significantly larger quantities than it currently is.

As a fisheries resource, it has the potential to return a much greater value to fishers, and to the community more broadly, than it currently does. With Australians importing almost 70 per cent of the seafood they eat, there is a growing economic and social imperative to eat local.

But among fishers and fishmongers, Australian Salmon is often considered a bait species and not worth the care needed to prepare it for the dinner table. And this fish does need care; it is unforgiving of mistreatment.

A quick kill by brain spiking the fish, then bleeding and immediately chilling is considered best practice to maintain the quality of the flesh (see FRDC Aquatic Animal Welfare – Research). However, Australian Salmon are often harvested in large numbers from shallow water by hauling nets onto beaches, which can make clean and speedy processing a challenge.

It may be difficult in these conditions, but not impossible to maintain fish quality, as an FRDC-funded project led by Ken Dods has demonstrated. This project developed best practice processing techniques and quality standards for the fish in Western Australia, which has previously provided the majority of the national harvest, although volumes have fallen in recent years.

In other states, fishers might also purse seine fish onto vessels rather than beaches. Some make this choice to avoid sand contamination and improve processing; for others it’s part of compliance with state regulations that prohibit beach landings, such as in Tasmania and Victoria.

Consumer challenge

Tasmanian-grown Atlantic Salmon dominates consumer awareness so successfully that people expect Australian Salmon to be Atlantic Salmon grown in Australia, and so to have red flesh. Even canned salmon are red-fleshed species imported from the Northern Hemisphere.

Seafood providore and marketer John Susman has suggested that Australian Salmon may not just need rebranding – it may need a whole new name. He raised this prospect at the Australian Salmon workshop held in Melbourne earlier this year.

This was the first event to bring together Australian Salmon fishers, seafood processors and wholesalers in the hospitality, retail and export markets. They represented all states harvesting the species and all parts of the supply chain.

While participants discussed the issue of consumer expectations, there was no consensus at the workshop to pursue a name change. They did agree that there was significant potential in working together to develop new markets, and to focus on increasing the value of fish, rather than on harvesting greater volumes.

Seafood post-harvest scientist Janet Howieson from Curtin University organised the workshop, saying some foundational work for the species has already been completed. This included the development of a quality index for grading the fish, assessment of processing practices to preserve quality, sensory comparison tests with other fish species, and product development options. She said earlier research projects had also identified that the name and consumer expectations were a barrier to greater consumer acceptance. However, she said it was up to the industry itself to take action on these issues.

Collaborative action

Workshop participants developed three priorities for collaborative action to raise the profile and the value of the species, which were:

- collating national data;

- supplying detailed information on the species to supply chain partners; and

- jointly investigating new markets.

Workshop participants also agreed to support the Seafood Trade Advisory Group in preparing submissions to have Australian Salmon added to the list of permitted species for export to China.

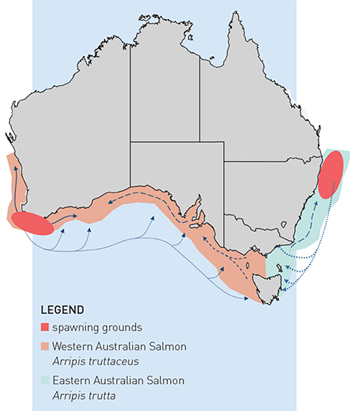

Distribution of Australian Salmon

Distribution of Australian Salmon.

Distribution of Australian Salmon. There are two closely related species of Australian Salmon, each of which forms a single, independent biological stock that crosses several fisheries jurisdictions.

The Eastern Australian Salmon (Arripis trutta) is found in southern Queensland, NSW, Victoria and Tasmania. Large mature fish are most commonly found off the coast of NSW. Eggs and larvae disperse and maturing fish return north to spawn, usually aged two to four years.

The Western Australian Salmon (Arripis truttaceus) is found in south-western WA, SA, Victoria and Tasmania. It spawns off south-west WA, with eggs and larvae dispersing eastward. Fish return west to spawn, usually aged three to five years.

The Western Australian Salmon species grows to 85 centimetres and 10 kilograms.

The Eastern Australian Salmon grows slightly longer, to 87 centimetres, but is lighter, at less than eight kilograms.

Retail market forays

Galvanised by the first national workshop on Australian Salmon, NSW fisher Tom Richardson and Queensland seafood processor Andre Gorissen from Noosa Seafood Market are embarking on a quality and retail market trial for the species.

Tom Richardson is supplying up to 50 kilograms of premium Australian Salmon.

Andre Gorissen will then process the fish using an organic modified atmosphere processing system called Fresh-tec, which he currently uses for up to 15 of the species he processes for domestic and export markets. This flavourless smoke technology stabilises the colour of fish and extends shelf life for both fresh and

frozen products.

Stabilising the colour is crucial, Andre Gorissen says, because consumers “buy with their eyes”. No matter how fresh or tasty a fish is, it needs to look good too. One of the challenges with Australian Salmon, and similar pelagic fish, is that the bloodline oxidises and quickly changes from red to brown, which makes the fish look unappealing. But with the right handling by the fisher and appropriate processing, this colour change can be prevented.

Testing the market with the processed product is the first step, and Andre Gorissen is excited about its potential for Australian Salmon and other underutilised species.

“We have a sustainable wild-caught product, from a clean, green environment, and the technology exists to process this the right way if the fisher can deliver a premium product.”

He says while Australian consumers are often unadventurous when it comes to seafood, and rely on the same few species over and over again, there are four billion people on Australia’s doorstep who think seafood “is the best thing going”. Samples of the fish processed by Fresh-tec will be sent along with other Noosa Seafood orders to domestic customers, as well as to Hong Kong and Singapore.

In Victoria, Mitchelson Fisheries at Lakes Entrance has also embarked on premium retail trials, in conjunction with the Fish Shoppe at the South Melbourne Market, and with Lakes Entrance chef Samantha Mahlook at Miriam’s Seafood Restaurant. The Mitchelson family purse seine their catch, with about 200 kilograms of fish immediately bled and set aside in ice. Feedback from the Fish Shoppe has led to refinements in the processing to include slicing the fish across the tail, as is done for tuna. Samantha Mahlook has also developed a menu special of Australian Salmon crusted with macadamia and lime that has been well received by customers. She’s keen to make the fish a regular part of her menu, which features several locally caught species.

FRDC Research Codes: 2006-018, 2013-711.3, 2016-121, 2017-023, 2018-306; CRC 2008.794.10, 2008.794

More information

Janet Howieson

j.howieson@curtin.edu.au

Chris Izzo

christopher.izzo@frdc.com.au