Greater control over breeding processes is producing faster-growing, fatter and more resilient Sydney Rock Oysters, helping the native species gain ground in the marketplace.

By Dyani Lewis

Photos: NSW Department of Primary Industries

New South Wales marine scientist Mike Dove readily admits he is biased when it comes to Sydney Rock Oysters (Saccostrea glomerata). “For me, they’re a better tasting, better eating oyster,” he says.

He leads the oyster research team at New South Wales Department of Primary Industries (DPI), which has a long-established breeding program for Sydney Rock Oysters. It has three goals: improved disease resistance, superior growth and increased marketability.

Sydney Rock Oysters take twice as long to reach a premium market size compared to Pacific Oysters (Crassostrea gigas), which have been farmed in Australia since their introduction from Japan in the 1940s. This slower growth makes production of Sydney Rock Oysters a more costly, riskier prospect for farmers. Mike Dove says hatchery production of Sydney Rock Oysters presents an array of challenges compared to other species.

Efforts to improve breeding processes have been boosted through the recently completed three-year Future Oysters Cooperative Research Centre Program (CRC-P). This was funded through what was the federal Department of Industry, Innovation and Science, with contributions from industry, universities, state research agencies and the FRDC, which also administered the CRC-P research projects.

The CRC-P brought CSIRO, universities and industry together via the Select Oyster Company and the DPI breeding team at Port Stephens Fisheries Institute to focus on key aspects of oyster production, including breeding techniques. Refinements to these techniques are already paying dividends, accelerating development of faster-growing, more disease-resistant Sydney Rock Oysters.

Better breeding Since 2014, NSW DPI and the Select Oyster Company, in collaboration with CSIRO, have developed a “family-based” breeding approach to improve Sydney Rock Oyster production. This involves selecting individual mating pairs from known families.

“We have the full pedigree for all the families that we breed,” Mike Dove says. “It’s a very accurate method of breeding, in terms of being able to predict gains and ensure that important genes are passed on to the next generation, while having control over inbreeding levels.”

It is not just a question of which oysters to breed. Tweaks to how they are bred and reared are also speeding up the process. At the University of Newcastle, researchers have been looking at how hatchery conditions can improve the viability of eggs after they have been obtained from broodstock to further boost fertilisation success.

At the same time, work at the University of the Sunshine Coast is refining breeding runs. Researchers there are improving broodstock conditioning techniques and have identified a spawning-inducing factor that triggers ripe oysters to naturally release their eggs and sperm, instead of having to sacrifice the oyster to physically extract gametes. This work gives breeders greater control over the process and preserves precious broodstock.

Using naturally released eggs has the added benefit of increasing fertilisation rates, giving higher yields from each family that is created. The result has led to increased fertilisation rates in breeding runs from 27 per cent to 45 per cent. It has also reduced the number of broodstock required, which are limited and expensive, and cuts down the amount of time needed to get a breeding run underway.

“It’s a huge step forward for the program, making the breeding process more reliable,” says Mike Dove.

Other tweaks DPI has been working on in collaboration with CSIRO include controlling when the oysters mature and spawn. Out-of-season breeding using hatchery conditioning techniques has allowed the best families to be selected a year earlier, effectively doubling the speed of gains for certain desirable traits.

Overall, the improvements have slashed the time and cost of breeding new and improved oysters. “Previously, using the old techniques, we’d have to wait three years to select the right oysters,” Mike Dove says. “We’ve been able to bring that down to one year just by changing the time at which we breed oysters.”

Floating bags used for single seed Sydney Rock Oyster nursery culture.

Industry priorities

Deciding which characteristics to breed for has been the role of the Select Oyster Company, an industry body that distributes breeding families to commercial oyster hatcheries. Working with oyster farmers, the Select Oyster Company has identified three main breeding goals. The first is resistance to QX – short for ‘Queensland unknown’ – a disease that can ravage oyster farms in affected estuaries. The second is faster-growing oysters, so that production times can be reduced. The final challenge is for the first two goals to be achieved without sacrificing the resulting oyster’s condition.

“Normally there’s a trade-off between oyster growth and their conditioning in terms of how fat they are when you open your oyster,” says Matt Wassnig, a former oyster farmer who chairs the board of the Select Oyster Company. Breeders are now on track to produce an oyster that matures to market size 30 per cent faster than wild oysters by March 2021. In another few years, that growth advantage will hopefully come at no cost to the final oyster condition.

Disease resistance

Outbreaks of QX disease were first recorded in the 1970s. By 1976, scientists had identified the culprit of QX disease: the single-celled parasite Marteilia sydneyi. In NSW, only seven of the 40 estuaries where Sydney Rock Oysters are farmed have had outbreaks of QX disease, despite the fact the parasite can be found in most estuaries where Sydney Rock Oysters

are grown.

When outbreaks do occur, mortality rates in affected estuaries can run as high as 98 per cent. “But we don’t know when or where the next QX disease outbreak will be,” says Mike Dove. If stock on farms is not disease-resistant it can spell the end of Sydney Rock Oyster production in that estuary. It is little wonder then, that oyster farmers want a QX-resistant oyster.

A QX outbreak first hit the Georges River in Sydney in 1994, and breeders now use it as their testing ground for resistance to QX disease. Each year the NSW DPI team takes its selectively bred oyster families to Georges River, placing them in the water at the right time and location to expose them to QX disease. This field challenge identifies the most resistant families for breeding the next generation.

“We are very fortunate that QX survival is a heritable trait that’s passed on through breeding quite effectively,” says Matt Wassnig. “That meant we were able to have a really solid breeding goal in a reasonably short period of time.” That goal, to have 70 per cent of selected oysters resistant to QX disease, was achieved earlier this year.

There is an added benefit of breeding QX-resistant oysters. These oysters have formed the basis for ongoing research into general resilience traits, which is expected to help farmers ‘future-proof’ production against emerging threats such as climate change.

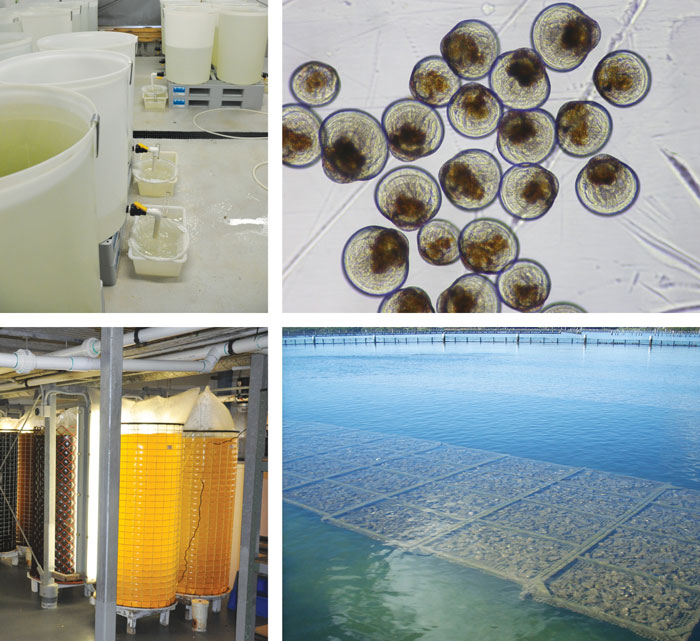

Clockwise from top left: Larval rearing tanks used for family production at Port Stephens Fisheries Institute; fifteen-day-old Sydney Rock Oyster larvae; bulk algal production at

Port Stephens Fisheries Institute for oyster spat and broodstock diets; ntertidal rack and tray culture of Sydney Rock Oysters.

Microbes as markers

It is possible that microbes living on and in Sydney Rock Oysters might hold some clues to improve oyster health and resilience. In a separate FRDC-funded project, researchers at the University of Technology Sydney (UTS) are investigating the microbial ecosystem – known as the microbiome – of the oysters, measuring which bacterial species proliferate and which decline under different conditions. This includes measuring how the microbiome differs between estuaries and under different environmental conditions, including disease pressure.

For example, oysters that are affected by a disease like QX often succumb to secondary bacterial infections. The UTS team is measuring changes in the microbiome through a QX disease outbreak to identify microbes that flag which oyster families are particularly robust. This research can be applied to gain greater understanding into other disease processes that impact Sydney Rock Oysters, such as winter mortality disease.

Winter Mortality resistance

“Winter Mortality is a significant issue for many estuaries where Sydney Rock Oysters are grown. The disease is quite unpredictable and very patchy and can kill up to 80 per cent of farmed stock in particularly bad seasons,” says Mike Dove.

The agent or agents that causes winter mortality are yet to be identified. It is possible that a range of factors are responsible, which makes breeding for resistance particularly difficult.

“We’re trying to understand the genetics of Winter Mortality disease resistance; we haven’t given up,” he says. “We still place oysters in a high-risk Winter Mortality site each year to try and get the information we need to keep improving Winter Mortality resistance in the breeding population.”

Year-round oysters

Currently, sales of Sydney Rock Oysters drop off at the end of autumn when the oysters have spawned out, but producers would love to have oysters available to sell year-round. To reach this goal, the DPI research team is also working to improve commercial production of triploid oysters. Normally, oysters are diploid, meaning they have two sets of chromosomes. Triploids have three sets

of chromosomes. Not only do triploids grow faster, they have a plump, saleable meat condition in months where diploid oysters have no market condition whatsoever.

Pacific Oyster farmers have been growing triploid oysters to extend their season since 1985, but the Sydney Rock Oyster industry is yet to develop a stable supply of triploids for industry.

Hatcheries make triploids by crossing male tetraploids – oysters with four sets of chromosomes – with eggs from regular diploids. DPI has been working with the Southern Cross Shellfish hatchery in Port Stephens to develop techniques to create tetraploid oysters, which will make production of triploid oysters more reliable for industry.

However, making Sydney Rock Oyster tetraploids is a finicky business. Diploids are chemically treated to form triploids, which are then treated again to form tetraploids. The perfect conditions for the two-step process are still being optimised, but success rates are steadily improving.

“If we can produce Sydney Rock Oyster tetraploids, industry can do more effective triploid oyster runs,” says Mike Dove. “Producers will have oysters that grow faster due to both being triploid, as well as genetically selected for better growth.”

In all, he says, gains across several aspects of the breeding and production process are now approaching commercial realisation, improving farm productivity to bring the delicacy of Sydney Rock Oysters to more diners, more often. The Sydney Rock Oyster breeding program also provides a strong foundation from which to respond to any unidentified future problems and needs, supporting the long-term sustainability of the industry.

FRDC Research Codes: 2016-802, 2016-803, 2016-805

More information

Michael Dove, 02 4916 3807, 0409 304 210, michael.dove@dpi.nsw.gov.au