Australian fish stocks added to international research efforts

By Catherine Norwood

International researchers are using global fish stock assessment datasets to produce new, high-profile research on the status of the world’s commercial fisheries.

But Australian fisheries are largely missing from the datasets these researchers use, despite the country’s reputation for world-class fisheries management. A new research project led by Richard Little at CSIRO is working to address this issue and provide more up-to-date Australian data to the international information pool.

In this case, it is the RAM Legacy Stock Assessment Database, publicly accessible, which forms the basis of fish stock analysis by researchers involved in the Science for Nature and People Partnership (SNAPP) fisheries measures program.

Ray Hilborn, a professor at the University of Washington in the US, leads the SNAPP fisheries measures research team. His international team has had articles published in high-profile journals including Science and Nature and is working on questions such as whether contemporary science-based fisheries management is effective in reducing overfishing.

Currently only a small portion of Australia’s Commonwealth fish stocks are included in the RAM database. Of those that are, much of the information is out of date. The issue, Richard Little says, is not that the information does not exist, but that it has been stored in such a way – particularly the raw datasets – that it is not easily accessible to others.

“So when international teams like Ray Hilborn’s publish their research on commercial fish stocks, information about Australian stocks is either missing or it doesn’t reflect the current stock status and management,” he says.

He is working to change this by developing standard processes and a “pipeline” that will allow national stock assessment datasets to be supplied to the RAM database. This includes securing permission from the owners of the data – in the case of Commonwealth fisheries, the Australian Fisheries Management Authority.

The first dataset he has “harmonised” for the RAM database is the Southern and Eastern Scalefish and Shark Fishery, specifically data on Redfish, School Whiting and Orange Roughy. Future updates will include the Patagonian Toothfish and Southern Bluefin Tuna.

He says the aim is to ensure the ways in which data are collected and handled align with other processes, such as the provision of data for the Status of Australian Fish Stocks Reports published by the FRDC.

From fisheries resources to seafood consumption, conversations are underway to maximise investment and outcomes in the evolving data landscape

New technologies, underpinned by data, will create efficiencies and uncover opportunities – from untapped markets to smarter fishing to better use of feed in aquaculture systems.

As a broker of fisheries information and data and a stakeholder in the sector, the FRDC is keen to maximise the returns that emerging opportunities afford. This is why it is facilitating a conversation involving industry and government to determine how to best take advantage of these new data-related opportunities.

To ensure a strategic approach that makes the best use of resources and addresses priorities, the FRDC will work with its stakeholders to develop a strategy to help guide investment and activities in this area.

Industry and government stakeholders have identified data as a priority. In the Australian Government’s State of the Environment Report 2011, one of the leading issues raised is the lack of an integrated national system for assessment and reporting of marine conditions. Despite the existence of fisheries assessment data, it was not coordinated or easily accessible.

In 2013, the FRDC began to coordinate the Status of the Australian Fish Stock (SAFS) Reports in response to that shortfall identified in that report. The success of the reports shows that high-level coordination between jurisdictions is achievable. However, the process brought to light many of the key questions that need to be asked when we are approaching the issue of data.

Some of these are being scoped by the Fisheries Statistics Working Group – a committee of the Australian Fisheries Management Forum. This includes setting out standard approaches to data and developing common terminology and common metadata standards.

Other issues, such as confidentiality, data ownership and the costs involved in harmonisation and collection still need to be looked at. Establishing the right governance and accountability is also key, as is shown by the way New Zealand manages its fisheries data (see Outsourced data delivery a win for NZ).

More recently, there have been significant efforts to broaden the scope of data that the FRDC collects. For example, in 2015 the seafood trade dashboard was revitalised and made available on the FRDC’s website. This now gives access to trade data in a way that can be interrogated and is easily understandable so that businesses can use this information in their business and strategic decision-making.

One longer-term dataset – the Australian fisheries and aquaculture statistics – has been produced annually for more than a decade and is a valuable source of information. However, changing business requirements, combined with new technologies, have highlighted that even this publication will need to evolve to deliver more timely data for stakeholders.

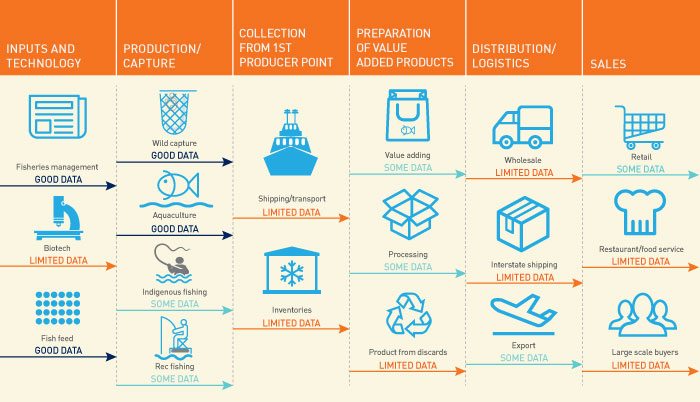

The first phase of the FRDC’s data strategy will be to map out the priority areas based on stakeholders’ needs or potential returns and then put in place mechanisms to address them. This process is already underway. As a basis for future decisions the FRDC is identifying:

- where good data exists and is readily available;

- where some data exists but requires work to be useable or useful if, for example, it is fragmented in multiple systems or must be purchased; and

- where limited or no current data exists.

The supply chain diagram (Figure 1) highlights several gaps in the data landscape. While this diagram gives a good basic overview of the key areas of data, it does not cover all potential data sources.

The FRDC has always been in the business of information – funding research to learn more about biology, ecology, environmental systems and population dynamics, and more. Many decisions across all of the fishing and aquaculture sector rely on this data.

However, technological changes and the digitisation of most forms of data mean the scope for investment is changing. In parallel with conversations about data in the world at large, the fisheries sector is discussing where it should place its resources and how to be ready for the new opportunities.

Given the complexity of collecting and looking after data in each of the areas identified in Figure 1, it is likely planning will be needed for each category of data. The stories in this issue on the Which Fish database (Risk reviews beyond fish stocks) and ‘Data-smart fishing’ show conversations are already underway.

It is important that the FRDC and stakeholders clearly articulate what is needed before we start collecting data – in other words, it will actually be used; and second, that the data that is collected is managed and made available in a way that can be accessed by end users.

Figure 1 Fisheries supply chain and existing Australian data availability.

Figure 1 Fisheries supply chain and existing Australian data availability.